Albert Einstein’s Brilliant Politics

TL;DR

Albert Einstein was not only a groundbreaking physicist but also a committed activist against segregation and for social justice in America. His optimism and ethical vision, rooted in scientific and humanistic principles, remain vital today.

Key Takeaways

- •Einstein actively opposed American segregation, drawing from his experiences with Nazi persecution and engaging with the African American community in Princeton.

- •He collaborated with figures like W.E.B. Du Bois and Paul Robeson, advocating for anti-lynching laws and racial equality through public writing and political action.

- •Einstein's scientific pursuit of a unified field theory paralleled his political goal of challenging false divisions and promoting human freedom and curiosity.

- •His legacy emphasizes that scientific discovery and social transformation are collective efforts, not solo acts, requiring solidarity and community engagement.

Einstein was among the first faculty members of the Institute for Advanced Study, which was founded in 1930 as an independent research center against the backdrop of fascism’s rise in Europe. He was a faculty member at IAS, which was initially housed at Princeton University, from 1933 to 1955, setting down roots in the town as he and the growing institution changed the trajectory of the modern world. This fall, I’m a visiting fellow at the institute, and the opportunity has inspired me to think about the wide range of subjects he explored while living here: not just his study of general relativity, quantum theory, and statistical mechanics, but also his devotion to the cause of human freedom. His critical optimism, rooted in a rigorous scientific worldview and a deeply humanistic sensibility, is imperiled today in a cultural moment marked by broad skepticism of scientific research and the promise of higher education. If we hope to revive and reclaim this persistent hope, his story—and the ethical vision it helps to illuminate—is a good place to begin.

The Princeton that Albert Einstein knew in 1933 was sharply divided by the color line; a long-established border—marked by Witherspoon, John, and Jackson Streets—separated its predominantly Black neighborhood from the rest of town. Einstein walked or biked across this divide often as he traveled through Princeton—he famously never learned to drive—and that journey was often accompanied by the voices of the children of Witherspoon, many of them yelling questions from bedroom windows.

Years later, in interviews recorded by the researchers Fred Jerome and Rodger Taylor, several of the men and women who once were those children offered lovely, vivid descriptions of their neighbor. Mercedes Woods describes his wild white hair and unlaced shoes; Shirl Gadson remembers his frequent walks and talks with her mother, Violet; Henry Pannell recalls Einstein giving out nickels to the neighborhood kids before sitting with Henry’s grandmother on the porch. Shirley Satterfield, a local legend and historian of African American life in Princeton, remembers meeting Einstein while spending the day with her mother, Alice, who worked as dining staff at IAS more than 70 years ago. When Shirley asked her mother what she and Einstein had talked about, she told her, simply, “the weather, or whatever.” His local reputation—as someone whom you could ask anything, anytime—was an outgrowth of his lived relationship with this community.

Read: Atomic war or peace

Einstein’s opposition to segregation was already well known in some quarters by the time he moved to Princeton. In 1932, W. E. B. Du Bois published a letter from him in The Crisis, one of the nation’s most prominent Black publications, in which the scientist offers the idea that racialized self-hatred, though often imposed by the majority, could be defeated through a communal practice of education and self-empowerment, “so an emancipation of the soul of the minority may be attained.” This was the aim of so much of Einstein’s public political writing: a conscious shift in perception, engineered via collective effort. To me, this seems like an extension of his scientific thinking—a theory of change made to the measure of a human life. In his letter to Du Bois, Einstein’s focal point is the structure of human cognition: how socially sanctioned prejudice corrupts our mental models of the world and ourselves. I don’t think this can be easily separated from his interest in the fundamental workings of motion and time, or his belief that, as he once wrote, the “most beautiful logical theory means nothing in natural science without comparison with the exactest experience.”

Throughout his career, one of Einstein’s core projects was what he called “unified field theory”: a single, elegant framework that would help us better understand the forces giving form and structure to the universe. This pursuit was also representative, I think, of Einstein’s larger political project—his desire to challenge false schemas of perceived difference. These distortions keep us from seeing fundamental truths about the nature of mortal life: that we are irreducibly complex, atoms and air, opaque to one another in ways that demand curiosity rather than surety. In “Geometry and Experience” he writes, “As far as the laws of mathematics refer to reality, they are not certain; and as far as they are certain, they do not refer to reality.” Everything we see, on this plane of perception, is in a state of endless transformation.

Einstein’s commitment to the creation of a new world, through both direct protest and everyday acts of solidarity, is visible in his relationships with artists and freedom fighters such as Paul Robeson, a native son of Princeton, whom he met in 1935 amid a national increase in extrajudicial killings of African Americans. At Robeson’s invitation, Einstein became a co-chair of the American Crusade to End Lynching. He also wrote a letter to President Harry Truman requesting the passage of a federal anti-lynching law. This sort of political activity eventually made Einstein a target of J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI, which surveilled him through his final years. At the time of his death, his FBI file was 1,427 pages long.

When the opera singer Marian Anderson performed a sold-out show in 1937 at Princeton’s McCarter Theatre—the same venue where Einstein had first met Robeson two years earlier—she was barred from staying at the segregated Nassau Inn next door to the campus. Though they had never met before that day, Einstein offered her his home. They would remain friends until the end of his life. During a 1940 speech at the World’s Fair in Queens, New York, beside an exhibit honoring notable immigrants, Einstein described Black music as “the finest contribution in the realm of art which America has so far given to the world.” He went on to say: “And this great gift we owe, not to those whose names are engraved on this ‘Wall of Fame,’ but to the children of the people, blossoming namelessly as the lilies of the field.”

Read: The scientist and the fascist

Among the great surprises of Einstein’s archive are the letters written to him by children across the world. A girl named June asked whether he was a real person or a fictional character. Others wanted to know how a bird’s feathers attain their color, or wished that he would settle schoolyard debates about whether life could exist without the sun (he responded with a litany of life-forms that need sunshine to survive). The subject of Tyfanny’s note is infinitude. After describing her daily practice of looking out the window to study stars with her boarding-school friends, and relaying her excitement about learning that Einstein was not dead after all, as she had initially assumed, she asks: “How can space go on forever?” Einstein replies with a combination of solemnity and wit: “Thank you for your letter of July 10th. I have to apologize to you that I am still among the living. There will be a remedy for this, however.” After answering Tyfanny’s question, Einstein ends his note with a larger claim about intellectual freedom and state control:

I hope that yours and your friend’s future astronomical investigations will not be discovered anymore by the eyes and ears of your school government. This is the attitude taken by most good citizens toward their government and I think rightly so.

I spent weeks searching for the historical Einstein at IAS—whose online database is named Albert, in his honor—and every time I logged on, I happened upon some new and unexpected figure in the ensemble of his life. As I tried to home in on the man so often perceived as a solitary genius, Albert seemed to point me elsewhere: to Einstein’s walking companions and their children; to Robeson, Anderson, and Du Bois; and even to the Institute Woods, the nature preserve that adjoins IAS. I learned that an African American family, the Bedfords, once lived in a house there. According to one interview, they were “due to get electricity” at some point from the institute. But they eventually had to move, and their home was destroyed.Through a combination of interviews and archival searches, I soon learned of other local families displaced over the years as the town continued to transform: the Montgomeries, the Wrights. Hearing and reading these names, I thought of Bruce Wright, born in Baltimore and raised in Princeton; he was admitted to Princeton University in the 1930s. During his first day on campus, once the administration realized that it had offered a place to a Black student, his admission was revoked and he was asked to leave. In 1935, IAS—still on Princeton’s campus—had attempted to recruit its first Black visiting fellow, a mathematician named William Claytor, and was overruled by the university administration. In 1939, the year the institute moved to a separate campus, it offered Claytor a fellowship, but he rejected the offer on principle. These sorts of stories reflect the Princeton that Einstein lived in—and did his best to navigate with integrity.

Alongside essays such as “Freedom and Science,” in which Einstein writes that “spiritual development and perfection” are possible only when “outward and inner freedom are constantly and consciously pursued,” I found photos of him walking across campus alone, but also some of crowded parties with Einstein at the center of the action, as well as shots of him working in the community to achieve his vision of beauty and justice. I also saw pictures of workers in the mail room, kitchen, and grounds who had helped keep the institute running after Einstein was gone—people such as James H. Barbour Jr., who had managed the buildings and grounds at IAS for two and a half decades, and Gary Alvin, who had worked in the mail room for 39 years, drove faculty to and from campus, and documented everyday life with his camera. While in search of one man’s story, I found a constellation of others. This is one of the great lessons of Einstein’s legacy: that the work of scientific discovery, like the work of social transformation, is no solo act. We must learn to live for one another.

Read: Why so many MIT students are writing poetry

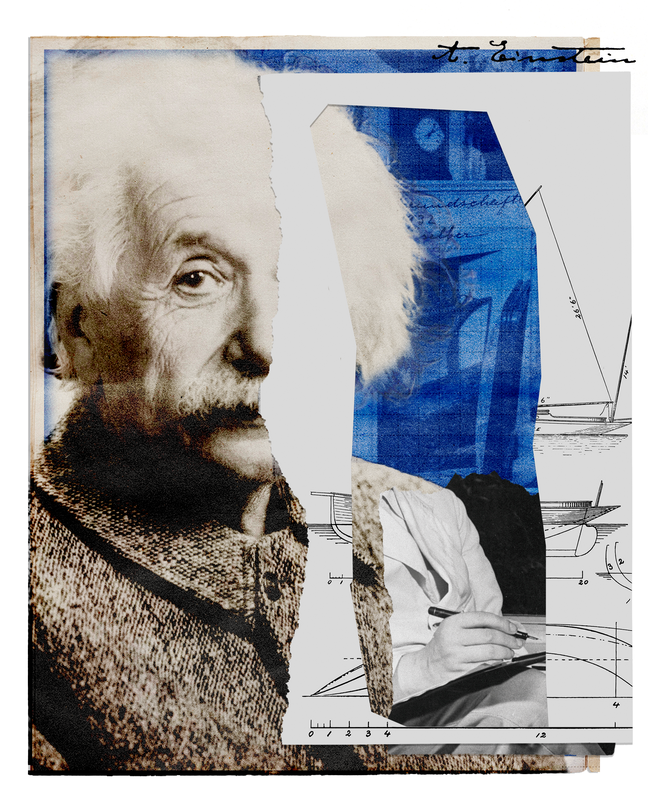

My first trip to IAS was 16 years ago, at the invitation of Adventures of the Mind, an organization devoted to creating mentorship opportunities for promising high-school students. I was there to read poems alongside two former U.S. poets laureate, Billy Collins and Rita Dove. During the official tour for the new fellows this past September, I noticed all sorts of things that I hadn’t during my first trip here: the lake where visitors skate once frost covers the grounds in winter, the Bauhaus-style apartments housing fellows and their families, the elegant shape of the large linden tree behind Fuld Hall, where Einstein’s office was once located. A small group of us was guided through a campus that features Einstein’s influence at every turn (multiple statues bear his likeness). In the director’s office, there is even a blueprint on the wall depicting a sailboat that was built for him.

Out of everything we saw on the campus tour, this singular image became an obsession of mine: framed schematics for a vessel lost to history. Searching the archives, I discovered this anecdote about Einstein sailing in Europe:

While his hand holds the rudder Einstein explains with joy his latest scientific ideas to his present friends. He sails the boat with the skill and fearlessness of a child. He himself hoists the sails, climbs around on the sailing boat to tighten the tows and ropes and handles bars and hooks to set sails. The joy with this hobby can be seen in his face, it echoes in his words and in his happy smile.

Three years before Einstein arrived in the United States, a relative offered this description of him aboard his 23-foot sailboat, a gift he had received for his 50th birthday. Tümmler it was called, from the German for “porpoise.” The vessel was seized (along with everything else he had left behind) by the Gestapo in 1933, despite Einstein’s best efforts to rescue it from afar. He even inquired after it in 1945, at the end of the war, but was never reunited with it. Learning this, I realized that the first images that I had seen of Einstein sailing were not aboard the Tümmler, but on the boat he kept here on the East Coast: Tinnef, the name derived from Yiddish and meaning “cheaply made.” In hindsight, the moniker seems like both a straightforward description and a refusal to forget the gift that was stolen from him.The IAS archives contain other sailing photos, all attesting to Einstein’s quiet intensity, the sense of a man both constantly in motion and at peace. I’ve thought a fair amount about why these photographs, in particular, resonated with me so strongly. Perhaps it’s the idea that in them, Einstein is headed somewhere we can’t see yet. I like to imagine that he’s moving toward the dream of the unified field, and toward a world set free from the illusion of irreconcilable separateness. That promise, I think, is still available. It lives on in those committed to the dream of the future world that he imagined: one more open, more free, shining and barely visible, just beyond the horizon.

*Lead-illustration sources: MPI / Getty; Buyenlarge / Getty; Three Lions / Hulton Archive / Getty; Universal History Archive / Getty; Bettmann / Getty.