Evaluating AI’s ability to perform scientific research tasks

TL;DR

AI models like GPT-5 are accelerating scientific research by performing complex tasks such as literature searches and mathematical proofs. OpenAI introduces FrontierScience, a new benchmark measuring expert-level scientific capabilities, where GPT-5.2 leads in performance. While models show substantial progress, significant work remains for open-ended research tasks.

Key Takeaways

- •AI models like GPT-5 are increasingly capable of accelerating scientific workflows, reducing tasks from days/weeks to hours.

- •OpenAI introduces FrontierScience, a benchmark with Olympiad and Research tracks to measure expert-level scientific reasoning and research abilities.

- •GPT-5.2 leads FrontierScience performance (77% Olympiad, 25% Research), showing progress but highlighting room for improvement in open-ended tasks.

- •Current models support structured reasoning in research but still require human judgment for problem framing and validation.

- •The field needs more difficult, original science benchmarks to better measure AI's potential for scientific discovery.

Tags

Reasoning is at the core of scientific work. Beyond recalling facts, scientists generate hypotheses, test and refine them, and synthesize ideas across fields. As our models become more capable, the central question is how they can reason deeply to contribute to scientific research.

Over the last year, our models have reached major milestones, including achieving gold-medal performance at the International Math Olympiad and the International Olympiad in Informatics. In parallel, we’re starting to see our most capable models, such as GPT‑5, meaningfully accelerate real scientific workflows. Researchers are using these systems for tasks such as literature search across disciplines and languages and working through complex mathematical proofs. In many cases, the model shortens work that might have taken days or weeks to hours. This progress is documented in our paper Early science acceleration experiments with GPT‑5, released in November 2025, which presents early evidence that GPT‑5 can measurably accelerate scientific workflows.

Introducing FrontierScience

As accelerating scientific progress is one of the most promising opportunities for AI to benefit humanity, we’re improving our models on difficult math and science tasks and working on the tools that will help scientists get the most from them.

When GPQA(opens in a new window), a “Google-Proof” science benchmark of questions written by PhD experts, was released in November 2023, GPT‑4 scored 39%, below the expert baseline of 70%. Two years later, GPT‑5.2 scored 92%. As models’ reasoning and knowledge capabilities continue to scale, more difficult benchmarks will be important to measure and forecast models’ ability to accelerate scientific research. Prior scientific benchmarks largely focus on multiple-choice questions, are saturated, or are not centrally focused on science.

To bridge this gap, we’re introducing FrontierScience: a new benchmark built to measure expert-level scientific capabilities. FrontierScience is written and verified by experts across physics, chemistry, and biology, and consists of hundreds of questions designed to be difficult, original, and meaningful. FrontierScience includes two tracks of questions: Olympiad, which measures Olympiad-style scientific reasoning capabilities, and Research, which measures real-world scientific research abilities. Providing more insight into models’ scientific capabilities helps us track progress and advance AI-accelerated science.

In our initial evaluations, GPT‑5.2 is our top performing model on FrontierScience-Olympiad (scoring 77%) and Research (scoring 25%), ahead of other frontier models. We’ve seen substantial progress on solving expert-level questions while leaving headroom for more progress, especially on open-ended research-style tasks. For scientists, this suggests that current models can already support parts of research that involve structured reasoning, while highlighting that significant work remains to improve their ability to carry out open-ended thinking. These results align with how scientists are already using today’s models: to accelerate research workflows while relying on human judgment for problem framing and validation, and increasingly to explore ideas and connections that would otherwise take much longer to uncover—including, in some cases, contributing new insights that experts then evaluate and test.

In the end, the most important benchmark for the scientific capabilities of AI is the novel discoveries it helps generate; those are what ultimately matter to science and society. FrontierScience sits upstream of that. It gives us a north star for expert-level scientific reasoning, letting us test models on a standardized set of questions, see where they succeed or fail, and identify where we need to improve them. FrontierScience is narrow and has limitations in key respects (for example, focusing on constrained, expert-written problems) and does not capture everything scientists do in their everyday work. But the field needs more difficult, original, and meaningful science benchmarks, and FrontierScience provides a step forward in this direction.

What FrontierScience measures and how we built it

The full FrontierScience evaluation spans over 700 textual questions (with 160 in the gold set) covering subfields across physics, chemistry, and biology. The benchmark is composed of an Olympiad and a Research split. FrontierScience-Olympiad contains 100 questions designed by international olympiad medalists to assess scientific reasoning in a constrained, short answer format. The Olympiad set was designed to contain theoretical questions at least as difficult as problems at international olympiad competitions. FrontierScience-Research consists of 60 original research subtasks designed by PhD scientists (doctoral candidates, professors, or postdoctoral researchers) that are graded using a 10-point rubric. The Research set was created to contain self-contained, multi-step subtasks at the level of difficulty that a PhD scientist might encounter during their research.

Sample questions

B1 reacts with aqueous bromine (Br2) to form B2. B2 reacts with potassium nitrite (KNO2) to form B3. B3 is nitrated in nitric acid (HNO3) and sulfuric acid (H2SO4) to form B4.

- B1 contains a monosubstituted aromatic 5-membered heterocycle and has a molar mass of 96.08 g/mol. It may be produced by dehydrating 5-carbon sugars (e.g. xylose) in an acid catalyst.

- B2 has the molecular formula C4H2Br2O3 and contains a tetrasubstituted alkene with 2 substituents being bromines cis to each other.

- B3 is a dipotassium salt with a molar mass of 269.27 g/mol. It contains 1 hydrogen.

- B4 is an achiral pseudohalogen dimer with 2 carbons, no hydrogens and a molar mass of 300. g/mol.

When B4 decomposes in solution, it forms an intermediate B5 and 1 equivalent of dinitrogen tetroxide (N2O4) as a side product. Intermediate B5 can be trapped and detected as a Diels-Alder adduct.

Provide the structures of B1, B2, B3, B4, and B5 in the following format, "B1: X; B2: X; B3: X; B4: X; B5: X".

Each task in FrontierScience is written and verified by a domain expert in physics, chemistry, or biology. For the Olympiad set, all experts were awarded a medal in at least one (and often multiple) international olympiad competitions. For the Research set, all experts hold a relevant PhD degree.

The Olympiad questions were created in collaboration with 42 former international medalists or national team coaches in the relevant domains, totalling 109 olympiad medals. The research questions were created in collaboration with 45 qualified scientists and domain experts. All scientists were either doctoral candidates, post-doctoral researchers, or professors. Their areas of expertise spanned an array of specialized and important scientific disciplines, from quantum electrodynamics to synthetic organic chemistry to evolutionary biology.

The task creation process for both sets included some selection against OpenAI internal models (e.g., discarding tasks that models successfully got right, so we expect the evaluation to be somewhat biased against these models relative to others). We open-source the Olympiad gold set of 100 questions and Research gold set of 60 questions, holding out the other questions to track contamination.

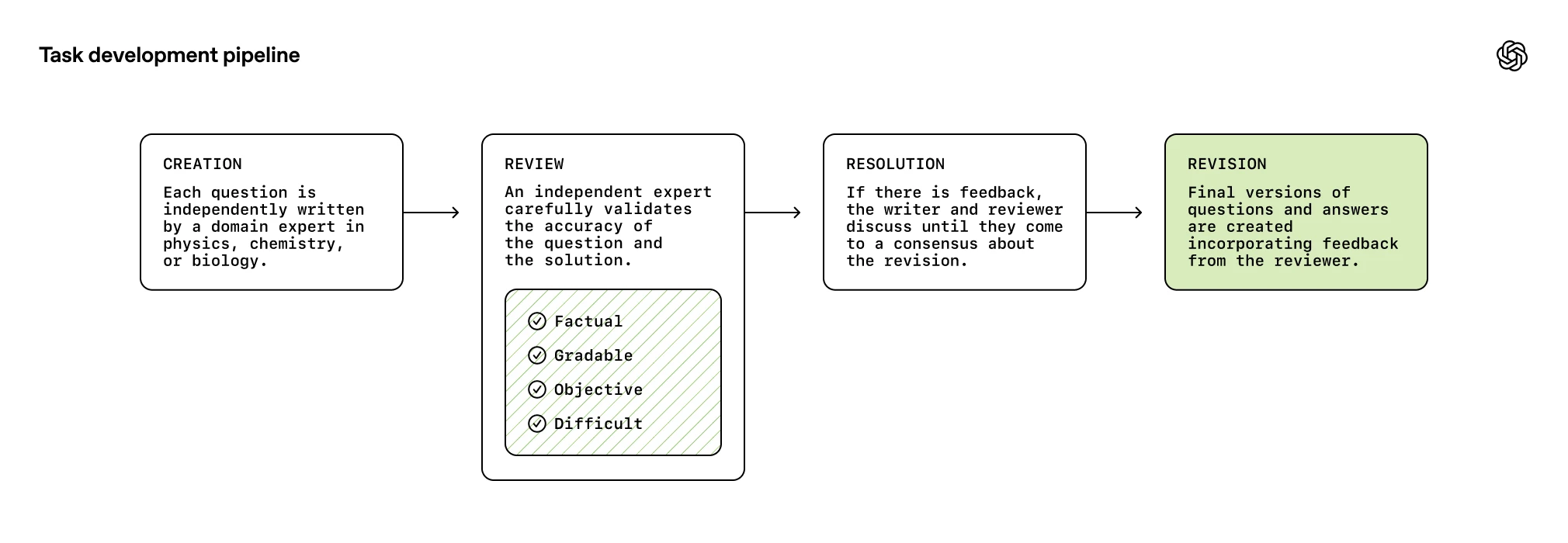

Tasks go through four stages: Creation, Review, Resolution, Revision. Independent experts review each other tasks to verify it aligns with the criteria.

How we grade model performance

The Olympiad set is gradable with a short answer: either with a number, expression, or fuzzy string match, which helps with verifying correctness. However, this verification often trades off with the expressivity and open-endedness of the problem. For the Research set, we introduce a rubric-based architecture for grading more open-ended tasks. Each question includes a scoring rubric with multiple independent and objectively assessable items, totaling 10 points. The grading rubric assesses not only the accuracy of the final answer, but also the correctness of intermediate reasoning steps, allowing for nuanced model performance and failure analysis. A solution is considered “correct” if it’s awarded at least 7/10 rubric points.

Responses are evaluated by a model-based grader (GPT‑5) against either the short answer or the rubric criteria. While we’d ideally use an expert human to grade each response, this approach is not scalable, so we designed the rubric to be checkable using a model grader. We developed a verification pipeline to help ensure rubrics and questions were well-calibrated to difficulty and correctness.

Sample chemistry research problem

Phthalocyanines are important macrocyclic compounds widely utilized in material and life sciences due to their outstanding physicochemical properties, including intense absorption in the visible-near-IR region and high electron-accepting ability. However, unlike porphyrins, the structural diversity of phthalocyanines has been limited by traditional synthetic methods that rely on one-step condensation of isoindoline units. The development of methodologies that allow controlled modification of the phthalocyanine framework, particularly at the meso-positions, represents a significant advancement in expanding the structural and electronic diversity of these compounds.

Analyze how the modification of meso-nitrogen atoms in nickel(II) phthalocyanine affects the electronic structure, aromaticity, spectroscopic properties, and reactivity of the resulting macrocycles. Explain the synthetic methodology that enables these modifications, the relationship between π-electron count and observed properties, and how these systems compare to traditional phthalocyanines and related porphyrinoids.

Sample response

1. Introduction: Why Modify the meso-Nitrogens of Phthalocyanines?

Phthalocyanines (Pc) are a class of macrocyclic dyes known for their remarkable chemical, electronic, and optical properties. Their widespread use in materials science, catalysis, and biology stems from strong absorptions in the visible/near-IR regions, exceptional redox characteristics (i.e., high electron affinity), and rigid π-conjugation. Traditional synthetic methods, however, typically form the macrocycle in a single step from phthalonitrile or isoindoline precursors, restricting the ability to introduce substitutions selectively at key ring positions-especially the "meso" (bridging) nitrogens. Recently, methodologies allowing targeted modification of the meso-nitrogen atoms in Ni(II) phthalocyanines have emerged as a powerful means to expand the structural and electronic diversity of these macrocycles.

2. Effect on Electronic Structure and Aromaticity

-

π-Electron Count and Ring Currents

Phthalocyanines are classical 18-electron aromatic systems, conferring high stability and planarity. Altering the meso-nitrogens through substitution or ring expansion can shift the effective π-electron count. For example, introducing additional unsaturated moieties or heteroatoms may expand the cyclic conjugation to 20 or 22 electrons, moving the molecule between Hückel aromaticity and other regimes that affect ring currents and magnetic properties.

-

Charge Distribution and Frontier Orbitals

Meso-substitution can tune the electron density distribution around the macrocycle. Electron-donating groups can push electron density toward the ring center, lowering the energy of the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO). Electron-withdrawing groups, conversely, stabilize the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and shift redox potentials toward more positive values, altering both the electrochemical profile and the Q- and B-band positions in the UV-vis spectrum.

3. Spectroscopic Consequences

-

UV-Vis Absorption (Q and B Bands)

The principal absorption features of phthalocyanines lie in the visible (Q-band, typically 600-700 nm) and near-UV (B-band, typically 300-400 nm).

Substitution that expands the ring conjugation or introduces strong electron-donating/withdrawing groups can:

- Shift the Q-band to longer wavelengths (bathochromic shift), reaching into the near-IR, which is highly desirable for optoelectronic and photodynamic applications.

- Alter relative intensities of these bands and merge or split them, reflecting changes in orbital symmetries and energies.

-

NMR Spectroscopy and Aromatic Ring Currents

Modifications to the π-electron count and distribution are directly observed in 1H and 13C NMR chemical shifts.

More highly conjugated (or expanded) aromatic rings exhibit distinct downfield shifts for protons located within induced ring currents, while any partial loss of aromaticity or incorporation of antiaromatic segments can cause atypical shielding/deshielding patterns.

4. Reactivity and Coordination Chemistry

Because phthalocyanines are often used as redox catalysts or sensors, the meso-nitrogen modifications can significantly influence reactivity:

- Electron-rich meso substituents facilitate nucleophilic or electrophilic attacks at the ring periphery, enabling site-selective functionalizations that are otherwise difficult.

(... shortened for the purposes of this figure)

Sample grading rubric

Analysis of Traditional Phthalocyanine Synthesis Limitations (1 point)

0.5 point: Mentions limitations of traditional methods but without specific focus on meso-position control challenges.

0.0 point: Fails to identify key limitations of traditional synthetic approaches or provides incorrect analysis.

Thiolate-Mediated Tetramerization Process (1 point)

1.0 point: Correctly describes the thiolate-mediated reductive tetramerization and explains how counter cation size (K+ or Cs+ vs. Na+) affects selectivity between tetramer formation and direct macrocyclization.

0.5 point: Mentions thiolate-mediated tetramerization but without explaining factors controlling selectivity.

Fail 0.0 point: Incorrectly describes the oligomerization process or omits critical details about selectivity control.Analysis of NMR Spectroscopic Features (1 point)

1.0 point: Correctly explains that upfield shifts in the 16π system indicate paratropic ring current (antiaromaticity), contrasts this with the broad signals in 17π systems due to paramagnetism, and connects these observations to the underlying electronic structures.

Pass 0.5 point: Identifies basic NMR patterns but without clear connection to ring currents or electronic structure.0.0 point: Incorrectly interprets NMR data or fails to connect spectral features to electronic properties.

Electrochemical Property Analysis (1 point)

1.0 point: Correctly explains that the 16π system shows two reversible reductions reflecting conversion to 17π radical and 18π aromatic states, while 17π systems show narrow redox gaps due to facile interconversion between 16π, 17π, and 18π states, and relates these patterns to the underlying electronic structures.

Pass 0.5 point: Describes redox patterns without clearly connecting them to specific electronic state changes.0.0 point: Incorrectly interprets electrochemical data or fails to connect redox behavior to electronic properties.

Analysis of Absorption Spectroscopy (1 point)

1.0 point: Correctly explains that the 16π system shows weak/broad absorption due to symmetry-forbidden HOMO-LUMO transitions in antiaromatic systems, while 17π systems show Q-like bands plus NIR-II absorptions characteristic of radical species, and contrasts these with typical phthalocyanine spectral features.

Pass 0.5 point: Describes absorption features but provides limited connection to underlying electronic structures.0.0 point: Incorrectly interprets absorption data or fails to relate spectral features to electronic properties.

Reactivity Analysis of Antiaromatic System (1 point)

1.0 point: Correctly explains the high reactivity of the 16π system toward nucleophiles, details specific reactions with hydroxide (ring opening) and hydrazine (ring expansion), and explains how these transformations relieve antiaromatic destabilization.

0.5 point: Mentions reactivity but provides limited analysis of specific transformations or the driving forces behind them.

Fail 0.0 point: Incorrectly analyzes reactivity patterns or fails to connect them to the antiaromatic character of the 16π system.(... and more)

Each task in the research set is graded using a rubric totaling 10 points that can be used by an expert or a model grader. To scale our ability to evaluate models, we use another model to grade responses.

Model performance

We evaluated several frontier models: GPT‑5.2, Claude Opus 4.5, and Gemini 3 Pro, GPT‑4o, OpenAI o4-mini, and OpenAI o3 on FrontierScience-Olympiad and FrontierScience-Research. All reasoning models were evaluated at “high” reasoning effort with the exception of GPT‑5.2 at “xhigh”. In our initial evaluations, GPT‑5.2 is our top performing model on FrontierScience-Olympiad (scoring 77%) and Research (scoring 25%), ahead of other frontier models. Gemini 3 Pro is comparable to GPT‑5.2 on the Olympiad set (scoring 76%).

We’ve seen substantial progress on solving expert-level questions, especially on open-ended research-style tasks. There is still more room to grow: from analyzing the transcripts for failures, frontier models sometimes made reasoning, logic, and calculation errors, didn’t understand niche scientific concepts, and made factual inaccuracies.

We compare accuracies across several frontier models. GPT‑5.2 is our highest performing model on the FrontierScience-Research and the Olympiad set.