Microbiota-induced T cell plasticity enables immune-mediated tumour control

TL;DR

Gut microbiota, specifically segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB), enhance immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) efficacy by inducing T cell plasticity. SFB-colonized mice show improved tumour control via gut-educated T cells that transform into pro-inflammatory TH1-like cells in tumours, boosting CD8+ T cell responses.

Key Takeaways

- •SFB colonization enables anti-PD-1 therapy to control tumours expressing shared antigens, highlighting microbiota's role in immunotherapy.

- •Gut-educated TH17 cells transdifferentiate into TH1-like cells in tumours, producing IFN-γ and TNF to remodel the tumour microenvironment.

- •This T cell plasticity enhances CD8+ T cell recruitment and effector functions, crucial for effective anti-tumour immunity.

- •Depletion of CD4+ or CD8+ T cells impairs ICB efficacy, showing their synergistic role in microbiota-mediated tumour control.

- •The study suggests targeted microbiota modulation as a strategy to broaden ICB effectiveness in cancer treatment.

Tags

Abstract

Therapies that harness the immune system to target and eliminate tumour cells have revolutionized cancer care. Immune checkpoint blockade (ICB), which boosts the anti-tumour immune response by inhibiting negative regulators of T cell activation1,2,3, is remarkably successful in a subset of cancer patients. Yet a significant proportion do not respond to treatment, emphasizing the need to understand factors influencing the therapeutic efficacy of ICB4,5,6,7,8,9. The gut microbiota, consisting of trillions of microorganisms residing in the gastrointestinal tract, has emerged as a critical determinant of immune function and response to cancer immunotherapy, with several studies demonstrating association of microbiota composition with clinical response10,11,12,13,14,15,16. However, a mechanistic understanding of how gut commensal bacteria influence the efficacy of ICB remains elusive. Here we use a gut commensal microorganism, segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB), which induces an antigen-specific T helper 17 (TH17) cell effector program in the small intestine lamina propria (SILP)17, to investigate how colonization with this microbe affects the efficacy of ICB in restraining distal growth of tumours sharing antigen with SFB. We find that anti-programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) treatment effectively inhibits the growth of implanted SFB antigen-expressing melanoma only if mice are colonized with SFB. Through T cell receptor (TCR) clonal lineage tracing, fate mapping and peptide–major histocompatability complex (MHC) tetramer staining, we identify tumour-associated SFB-specific T helper 1 (TH1)-like cells derived from the homeostatic TH17 cells induced by SFB colonization in the SILP. These gut-educated ex-TH17 cells produce high levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokines interferon (IFN)-γ and tumour necrosis factor (TNF) within the tumour microenvironment (TME), enhancing antigen presentation and promoting recruitment, expansion and effector functions of CD8+ tumour-infiltrating cytotoxic lymphocytes and thereby enabling anti-PD-1-mediated tumour control. Conditional ablation of SFB-induced IL-17A+CD4+ T cells, precursors of tumour-associated TH1-like cells, abolishes anti-PD-1-mediated tumour control and markedly impairs tumour-specific CD8+ T cell recruitment and effector function within the TME. Our data, as a proof of principle, define a cellular pathway by which a single, defined intestinal commensal imprints T cell plasticity that potentiates PD-1 blockade, and indicate targeted modulation of the microbiota as a strategy to broaden ICB efficacy.

Main

Although specific bacterial taxa have been associated with favourable clinical responses to immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) in cancer patients12,13,18,19,20,21,22, the mechanisms by which the intestinal microbiota influences anti-tumour immune responses remain poorly defined. Products of the microbiota, including metabolites23,24,25 and innate receptor ligands26, may reprogramme myeloid cells27, lowering the activation threshold for antigen presentation and thereby facilitating priming and activation of tumour-reactive T cells. Alternatively, T cells that recognize antigens shared between commensals (microbial-associated antigens (MAAs)) and tumours (tumour-associated antigens (TAAs)) may become activated in the setting of ICB, thus enhancing anti-tumour immune responses. Because the gut microbiome encodes an enormous antigenic repertoire, commensal-derived antigens can elicit T cell responses that, in some cases, cross-react with tumour epitopes—a plausible mechanism for commensal-driven tumour control28. Despite correlative clinical data29, the causality of such antigenic mimicry has not yet been demonstrated definitively in vivo. It is possible, however, to test this premise, particularly the relationship of microbe-specific T cells and intratumoural T cells, in animal models. An immunization model with skin-associated Staphylococcus epidermidis engineered to express antigens shared with implanted tumours was shown to elicit effective anti-tumour responses30, but the ability of gut commensals that elicit stereotyped T cell responses to program anti-tumour immunity has not been explored. Here we studied how a small intestine-resident commensal microbe, SFB, which induces a regulatory-like T helper 17 (TH17) cell response that enhances intestinal barrier integrity31,32, influences efficacy of ICB in controlling growth of distal tumours that share antigen with the bacterium. We found that tumour-specific TH17 cells, primed by SFB in the gut, infiltrate the tumour as trans-differentiated pro-inflammatory T helper 1 (TH1)-like cells following ICB. These cells remodel the tumour microenvironment (TME), promoting recruitment, expansion and maturation of CD8+ effector T cells that contribute critically to anti-tumour immunity. Our results indicate that defined constituents of the intestinal microbiota can be harnessed to elicit desired effector T cell programs that restrain tumour growth.

SFB promotes ICB-mediated tumour control

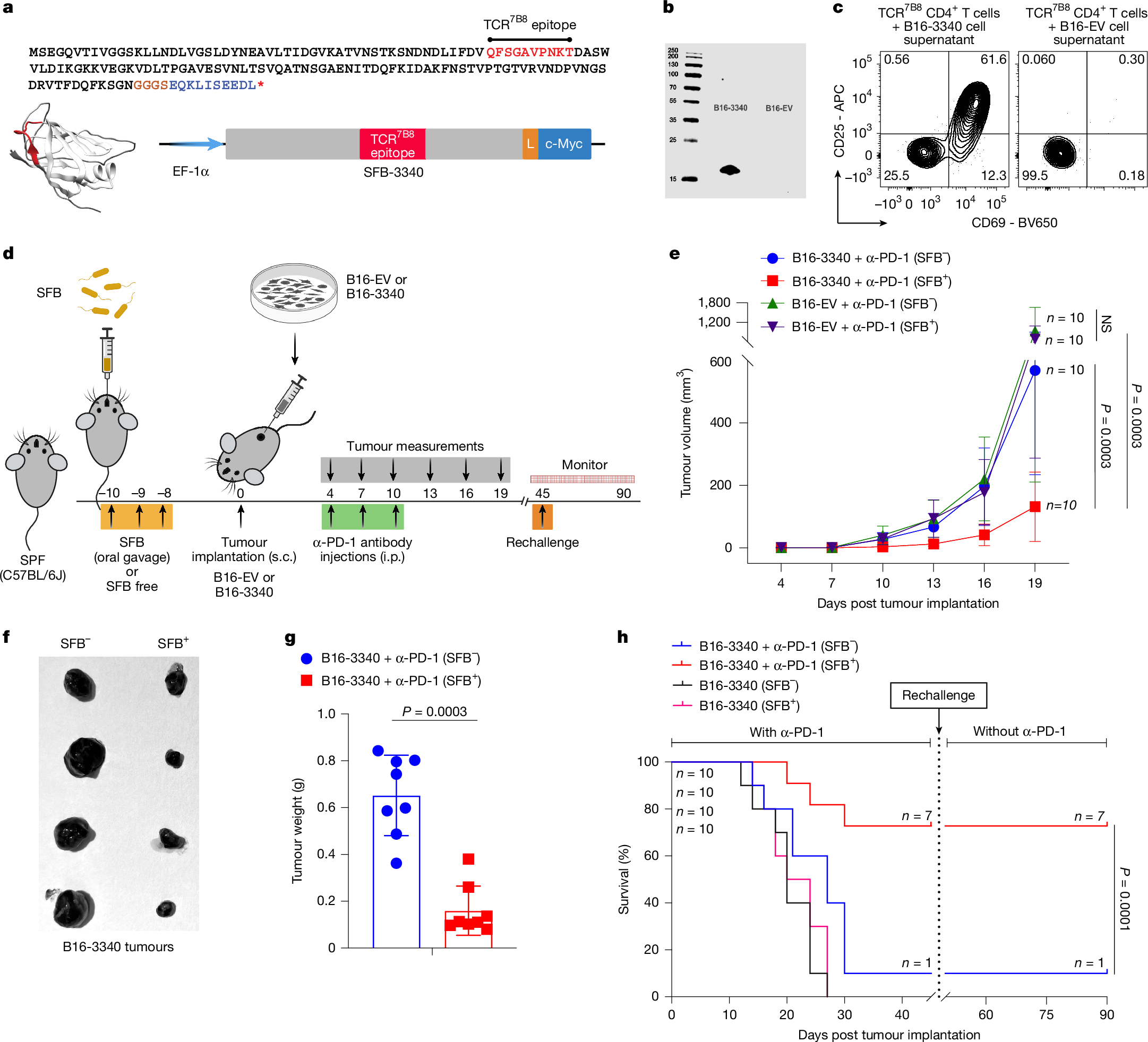

To explore how gut commensal microbiota influence immune-mediated tumour control, we developed a synthetic neoantigen mimicry tumour model in mice by engineering B16-F10 (B16-3340) melanoma cells to express an immunodominant protein fragment of the gut-colonizing commensal microbe SFB (Fig. 1a,b). We chose SFB because it reliably colonizes specific-pathogen-free (SPF) mice and elicits a robust, well-characterized CD4+ T cell response that can be tracked with peptide-MHCII tetramers and TCR-transgenic mice17,33,34. Lysates from B16-3340, but not from empty vector controls (B16-EV), robustly activated TCR-transgenic T cells (TCR7B8) ex vivo, demonstrating effective processing and presentation of the SFB-derived epitope (Fig. 1c).

a, Amino acid sequence of the SFB-3340 protein fragment containing the CD4+ T cell epitope recognized by TCR7B8 (red). The codon-optimized gene was fused to an EF-1α promoter (5′) and c-Myc tag (blue, 3′) by a flexible linker (L). s.c., subcutaneous. b, Immunoblot showing expression of the SFB-3340 fragment in transfected B16-F10 (B16-3340) cells, detected with anti-c-Myc antibody. Empty vector transfected cells (B16-EV) served as control. Size markers (kDa) are shown on the left. c, Ex vivo activation of naive SFB-specific CD4+ T cells from TCR7B8 transgenic mice co-cultured with syngeneic splenocytes plus lysates from B16-3340 or B16-EV cells. Surface expression of activation markers CD69 and CD25 was analysed 24 h later by flow cytometry. d, Experimental design comparing SFB-colonized (SFB+) and SFB-free (SFB−) C57BL/6J mice implanted with B16-3340 or B16-EV tumours. e, Tumour growth curves from caliper measurements (n = 10 mice per group). Mice received anti-PD-1 antibody (250 µg per mouse, i.p.) on days 4, 7 and 10 post-implantation. Data represent mean ± s.d.; significance determined by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Sidak’s correction. f, Representative B16-3340 tumours excised from SFB+ and SFB− mice on day 14 post tumour implantation. g, Excised tumour weights from SFB+ and SFB− mice on day 14 (n = 8 mice per group); mean ± s.d., unpaired two-sided Mann–Whitney test. h, Kaplan–Meier survival curves of SFB+ and SFB− mice (n = 10 mice per group) bearing B16-3340 tumours, with or without anti-PD-1 therapy. Following the initial challenge, surviving mice were re-challenged with the same tumour cells, and monitored without further anti-PD-1 antibody treatment. P values were determined by log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. All experiments in e–h were repeated independently at least twice with similar results. In panel a, the ribbon-helix model was generated using AlphaFold2 to illustrate the predicted structure of the SFB-3340 protein fragment containing the TCR7B8 epitope. This fragment was used to engineer cancer cell lines (B16-F10, MC-38 and LLC1) to stably express the SFB-3340 antigen, resulting in the generation of B16-3340, MC-3340 and LLC1-3340 cell lines. Schematics in a and d were created using BioRender (https://biorender.com).

Next, we examined the effect of SFB colonization on tumour growth in SPF mice (Jackson Laboratories) bearing subcutaneously implanted B16-3340 and B16-EV tumours, with (Fig. 1d) or without (Extended Data Fig. 1a) anti-programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) treatment. In the absence of PD-1 blockade, there was no notable difference in tumour growth between mice implanted with either B16-3340 or B16-EV, regardless of SFB colonization status (SFB+ or SFB−) (Extended Data Fig. 1b,c). However, when animals were treated with anti-PD-1 antibody, the growth of B16-3340 tumours was markedly reduced in SFB+ mice compared with SFB− mice. There was no notable difference in the growth of control B16-EV tumours between SFB+ and SFB− mice receiving anti-PD-1 treatment (Fig. 1e–g and Extended Data Fig. 1d). The combination of SFB colonization and anti-PD-1 treatment of B16-3340 tumours also conferred a survival advantage compared with the other groups (Fig. 1h). Mice that survived the primary B16-3340 challenge subsequently rejected tumour re-challenge even without additional anti-PD-1 treatment, demonstrating durable, memory-like protection mediated by SFB colonization in concert with ICB (Fig. 1h). This robust SFB-dependent enhancement of anti-tumour immunity prompted further investigation into the underlying mechanisms by which SFB modulates tumour-directed immune responses and potentiates the efficacy of ICB.

To test whether SFB can act therapeutically to enhance anti-PD-1 efficacy after tumour establishment, we performed staged post-implantation gavage experiments (Extended Data Fig. 1e). Mice bearing B16-3340 were treated with anti-PD-1 (days 4–10) and gavaged with SFB at defined intervals (days 8–12, 12–16 or 15–19) or left SFB-free. Early gavage (days 8–12, group 1) produced the largest reduction in tumour growth, with progressively diminished benefit for later administrations (groups 2 and 3) (Extended Data Fig. 1f), indicating a narrow post-implantation window in which microbial antigen exposure most effectively synergizes with PD-1 blockade. These data further show that tumour expression of the SFB-derived neoantigen is required for microbiota-dependent augmentation of anti-PD-1 and that therapeutic SFB colonization is most effective when delivered early.

We next determined whether antigenic mimicry promotes microbiota-mediated control of additional tumours, extending our study to Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC1-3340) and MC-38 colon adenocarcinoma (MC-3340). SFB-colonized (SFB+) or SFB-free (SFB−) C57BL/6J mice were implanted subcutaneously with these engineered tumour cells and treated with anti-PD-1 beginning at the earliest stage of palpable tumour growth (Extended Data Fig. 1g,i). In both tumour models, SFB+ mice exhibited substantially delayed tumour growth compared with SFB− cohorts (Extended Data Fig. 1h,j).

SFB alters tumour T cell profile

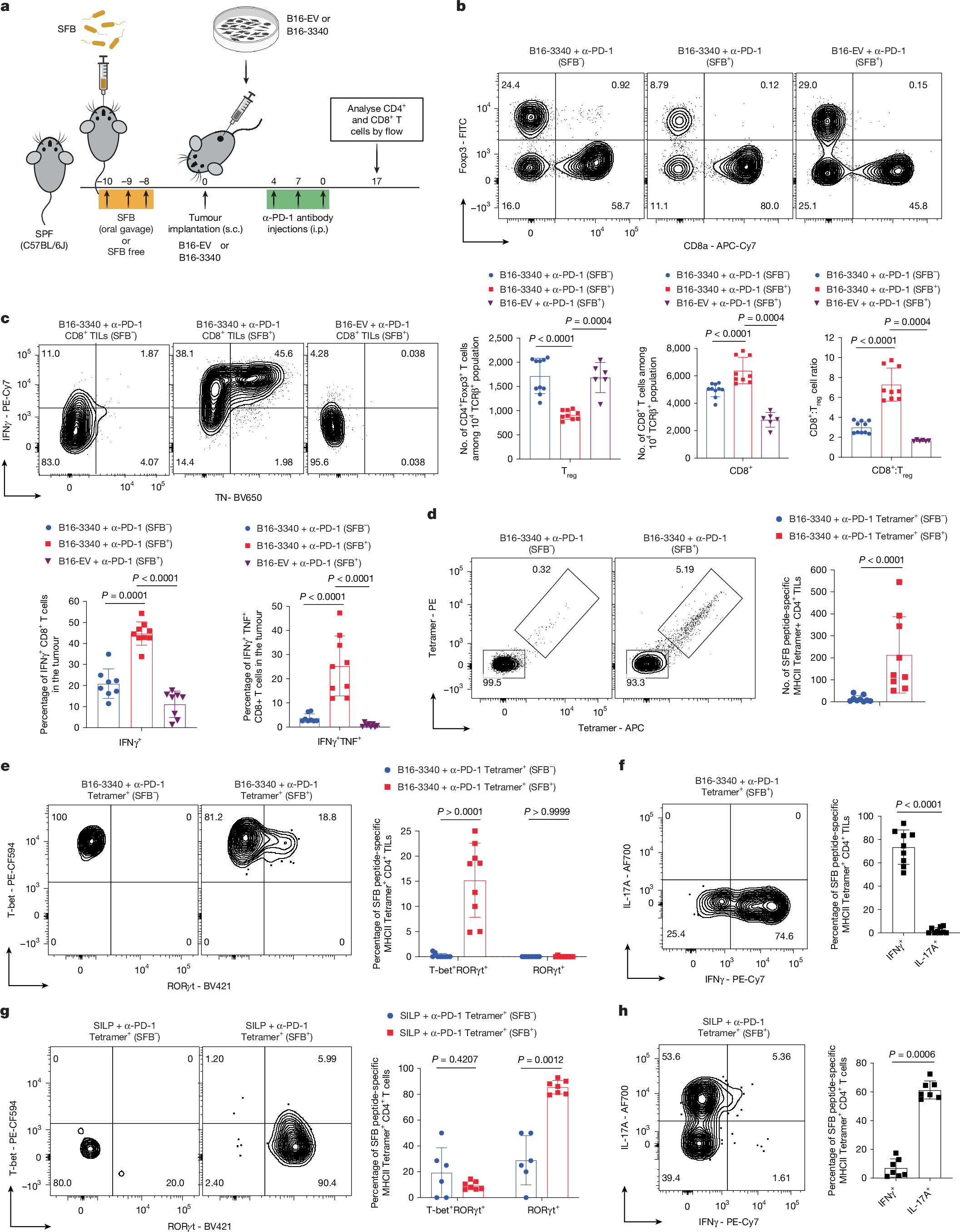

Profiling of T cells from B16-3340 and B16-EV tumours in anti-PD-1 treated SFB+ and SFB− mice showed that SFB colonization significantly increased the intratumoural CD8+ to regulatory T (Treg) cell ratio compared with either SFB− mice with B16-3340 tumours or SFB+ mice with B16-EV tumours subjected to anti-PD-1 treatment (Fig. 2a,b). In contrast, SFB colonization did not alter CD8+ to Treg cell ratio in the small intestine lamina propria (SILP) of anti-PD-1 treated mice (Extended Data Fig. 2a). Concurrently, CD8+ tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) from anti-PD-1 treated, B16-3340 tumours from SFB+ exhibited markedly enhanced effector functions, with higher frequencies of IFNγ+, TNF+IFNγ+ and Gzm-B+TNF+ CD8+ TILs compared with either CD8+ TILs in anti-PD-1 treated B16-3340 tumours in SFB− or B16-EV tumours in SFB+ mice (Fig. 2c and Extended Data Fig. 2b). Similar results were demonstrated previously in the microbiota-mediated response to PD-1 blockade35.

a, Schematic of the synthetic mimicry model used to evaluate how gut SFB colonization alters the distal immune TME. b, Top, representative flow cytometry plots of tumour-infiltrating CD8+ T cells and Foxp3+ CD4+ Treg cells from B16-3340 (SFB−, n = 10 mice and SFB+, n = 9 mice) and B16-EV (SFB+; n = 6) following anti-PD-1 treatment. Bottom, quantification of absolute counts of Treg cells, CD8+ T cells, and CD8:Treg ratio per tumour. c, Top, representative cytokine flow cytometry plots (TNF+ IFNγ+) of CD8+ TILs from B16-3340 tumours in SFB− and SFB+ mice, and B16-EV tumours in SFB+ mice. Bottom, frequencies of TNF+ IFNγ+ CD8+ TILs: B16-3340 (SFB−, n = 8), B16-3340 (SFB+, n = 9) and B16-EV (SFB+, n = 8). d, Left, SFB-peptide-specific MHCII tetramer staining of CD4+ TILs from B16-3340 tumours (SFB− versus SFB+). Right, absolute counts of tetramer+ CD4+ TILs per tumour (n = 9 mice per group). e, Left, expression of RORγt and T-bet in tetramer+ CD4+ TILs from B16-3340 tumours of SFB− and SFB+ mice. Right, frequencies of T-bet+RORγt+ and RORγt+ subsets (n = 9 mice per group). f, Left, IFNγ and IL-17A expression in tetramer+ CD4+ TILs from B16-3340 tumours in SFB+ mice. Right, frequencies of IFNγ+ and IL-17A+ tetramer+ CD4+ TILs (n = 9 mice per group). g, Left, RORγt and T-bet expression in SILP tetramer+ CD4+ T cells (SFB− versus SFB+). Right, quantification of transcription factor expression in SILP tetramer+ CD4+ T cells from SFB− (n = 6) and SFB+ (n = 7) mice. h, Left, IFNγ and IL-17A expression in SILP tetramer+ CD4+ T cells (SFB+). Right, frequencies of IFNγ+ and IL-17A+ SILP tetramer+ CD4+ T cells (n = 7 mice per group). Data are mean ± s.d., each data point representing an individual mouse. Statistical comparisons were determined by unpaired two-sided Mann–Whitney t-test, with P values indicated. All experiments shown were repeated at least twice with similar results. Schematic in a was created using BioRender (https://biorender.com).

Next, because SFB colonization induces antigen-specific TH17 cells in the ileal lamina propria, we compared the CD4+ T cell phenotypes in the remotely located B16-3340 tumours. First, using a panel of antibodies specific for TCR Vβs, we found a greater proportion of Vβ14+ CD4+ T cells in tumours from SFB+ compared with SFB− mice (Extended Data Fig. 2c). This bias is consistent with the known preferential interaction of this subset of TCRs with immunodominant SFB peptides in the SILP of SFB-colonized mice36 (Extended Data Fig. 2d). Second, using SFB-3340 peptide-loaded MHCII tetramers revealed that colonization with SFB caused increased infiltration of SFB-3340-specific CD4+ T cells into B16-3340 tumours (Fig. 2d). Remarkably, tumour-resident tetramer+ CD4+ T cells displayed an IFNγ producing TH1-like phenotype, unlike SILP tetramer+ T cells that, as expected, were IL-17A producing TH17 cells (Fig. 2e–h and Extended Data Fig. 2e–g). Although tumour-resident tetramer+ CD4+ T cells in both SFB+ and SFB− mice were T-bet+, a minor fraction from SFB+ mice co-expressed RORγt, consistent with gut imprinting (Fig. 2e and Extended Data Fig. 2g). By contrast, the bulk of tetramer− CD4+ T cells in both B16-3340 and B16-EV tumours, irrespective of SFB colonization, were regulatory-like T cells, expressing both T-bet and Foxp3 (Extended Data Fig. 2h,i), a phenotype associated with strong suppression of anti-tumour immune responses37.

ELISpot assays confirmed significant enrichment of IFNγ-producing CD4+ TILs in SFB+ B16-3340 tumours compared with SFB− cohorts (Extended Data Fig. 3a) and, accordingly, tetramer+ CD4+ TILs from those tumours exhibited a robust TH1 cytokine (IFNγ and TNF) response following ex vivo stimulation (Extended Data Fig. 3b). Furthermore, whereas the frequencies of both T-bet+Foxp3− and T-bet+Foxp3+ cells in the tetramer− CD4+ T cell population were comparable across groups (Extended Data Fig. 2h,i), B16-3340 tumours in SFB+ mice contained a significantly higher fraction of tetramer− CD4+ T cells that produced moderate amounts of IFNγ and TNF following ex vivo stimulation compared with either B16-3340 tumours in SFB− mice or B16-EV tumours in SFB+ mice (Extended Data Fig. 3c,d). Together, these findings suggest that SFB-specific pro-inflammatory CD4+ T cells contribute to remodelling the TME, thereby increasing its responsiveness to PD-1 blockade.

The T cell composition in the MC-38 tumours expressing the SFB antigen (MC-3340) was similarly altered, with SFB colonization promoting accumulation of tetramer+ CD4+ T cells exhibiting a T-bet+IFNγ+ TH1-like program, and an enrichment of IFNγ+Gzm-B+ CD8+ TILs (Extended Data Fig. 3e–h). These data show that SFB-induced antigen-specific CD4+ T cell priming and TH1-like polarization, together with enhanced CD8+ T cell effector function, potentiate PD-1 blockade across melanoma, lung and colon tumour models when the tumour expresses the cognate microbial epitope.

CD4+ and CD8+ TILs required for response

Next, given that the effective anti-tumour immune response requires synergistic cooperation of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in ICB-mediated tumour control38,39,40, we aimed to investigate whether the combination of SFB-induced CD4+ T cells and tumour-infiltrating CD8+ T cells, together with anti-PD-1 therapy, is essential for controlling B16-3340 tumour growth in SFB+ mice. In vivo depletion of either CD4+ (Extended Data Fig. 4a,b) or CD8+ (Extended Data Fig. 4a,g) T cells in B16-3340 tumour-bearing mice significantly impaired the efficacy of anti-PD-1 treatment (Extended Data Fig. 4c and 4h). CD8+ TILs from CD4-depleted, SFB+ mice exhibited a marked functional impairment, with significant reductions in T-bet+IFNγ+, TNF+Gzm-B+ and IFNγ+TNF+ cells relative to controls (Extended Data Fig. 4d–f), indicating that microbiota-dependent CD4+ T cells are critical for the acquisition of full CD8+ TIL effector function in tumours. Conversely, depletion of CD8+ T cells modestly reduced the proportion of T-bet+IFNγ+ CD4+ TILs, consistent with reciprocal but asymmetric cross-talk between these T cell lineages (Extended Data Fig. 4i,j). Together, these results demonstrate that SFB colonization enhances the efficacy of PD-1 blockade through a coordinated CD4–CD8 T cell axis: microbiota-induced, pro-inflammatory CD4+ T cells provide critical help for CD8+ TIL maturation and cytotoxic function, whereas both T cell subsets are jointly required for durable, SFB-dependent tumour control under anti-PD-1 therapy.

Shared T cell clonality in gut and tumours

To examine the relationship of intestinal and tumour-infiltrating T cells in SFB− and SFB+ mice with B16-3340 tumours, we performed paired single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) and TCR repertoire analysis (scTCR-seq) on sorted CD4+ T cells from SILP and B16-3340 tumours (Fig. 3a). Unsupervised clustering of the scRNA-seq data resolved transcriptionally distinct CD4+ T cell subsets in each tissue (nine clusters in SILP and ten in B16-3340 tumours), defined by canonical lineage markers (Extended Data Fig. 5a). As anticipated, SFB colonization selectively expanded an IL-17A+ TH17 cluster in the SILP (cluster 2) of SFB+ mice (Fig. 3b). In contrast, tumours from SFB+ mice were enriched for an IFNγ+ TH1-like subset (cluster 1), a population absent from tumours of SFB− mice (Fig. 3c), highlighting the divergent, tissue-specific programs of antigen-specific CD4+ T cells.