A nowhere-to-hide mechanism ensures complete piRNA-directed DNA methylation

TL;DR

The study reveals a 'nowhere-to-hide' mechanism in the mouse piRNA pathway, where SPOCD1 interacts with TPR to ensure complete LINE1 transposon DNA methylation by preventing piRNA factors from relocalizing to heterochromatin. This interaction guarantees accessibility of transposons to the methylation machinery across the entire genome.

Key Takeaways

- •The piRNA pathway uses a 'nowhere-to-hide' mechanism to ensure complete LINE1 transposon methylation by preventing piRNA factors from being sequestered in heterochromatin.

- •SPOCD1 directly interacts with TPR, a nuclear pore component, to maintain piRNA factors in euchromatic regions where they can access transposons.

- •Loss of the SPOCD1-TPR interaction causes piRNA factors to relocate to constitutive heterochromatin, making them inaccessible to MIWI2 and the DNA methylation machinery.

- •This mechanism ensures non-stochastic, comprehensive transposon surveillance throughout the genome during male germline development.

Tags

Abstract

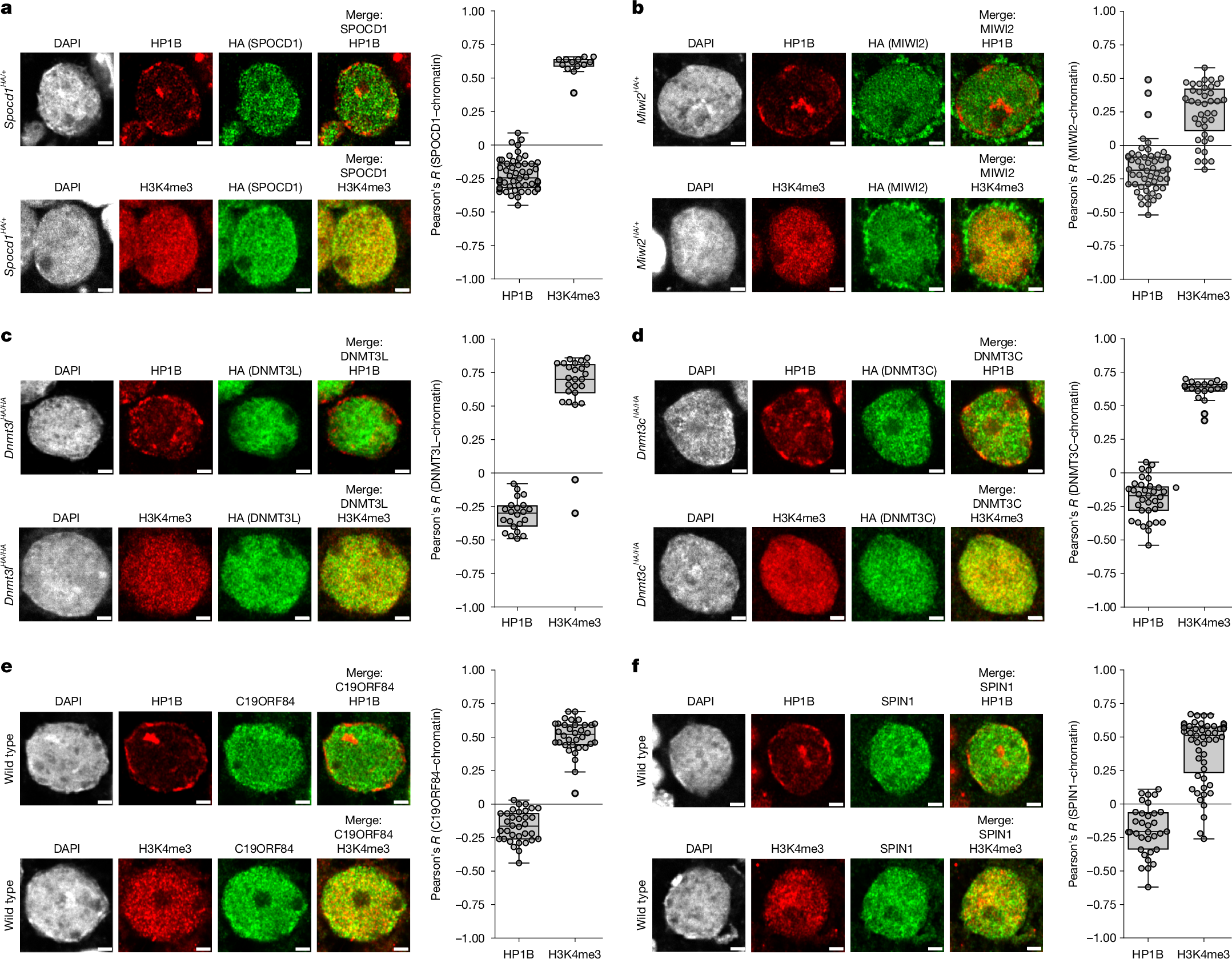

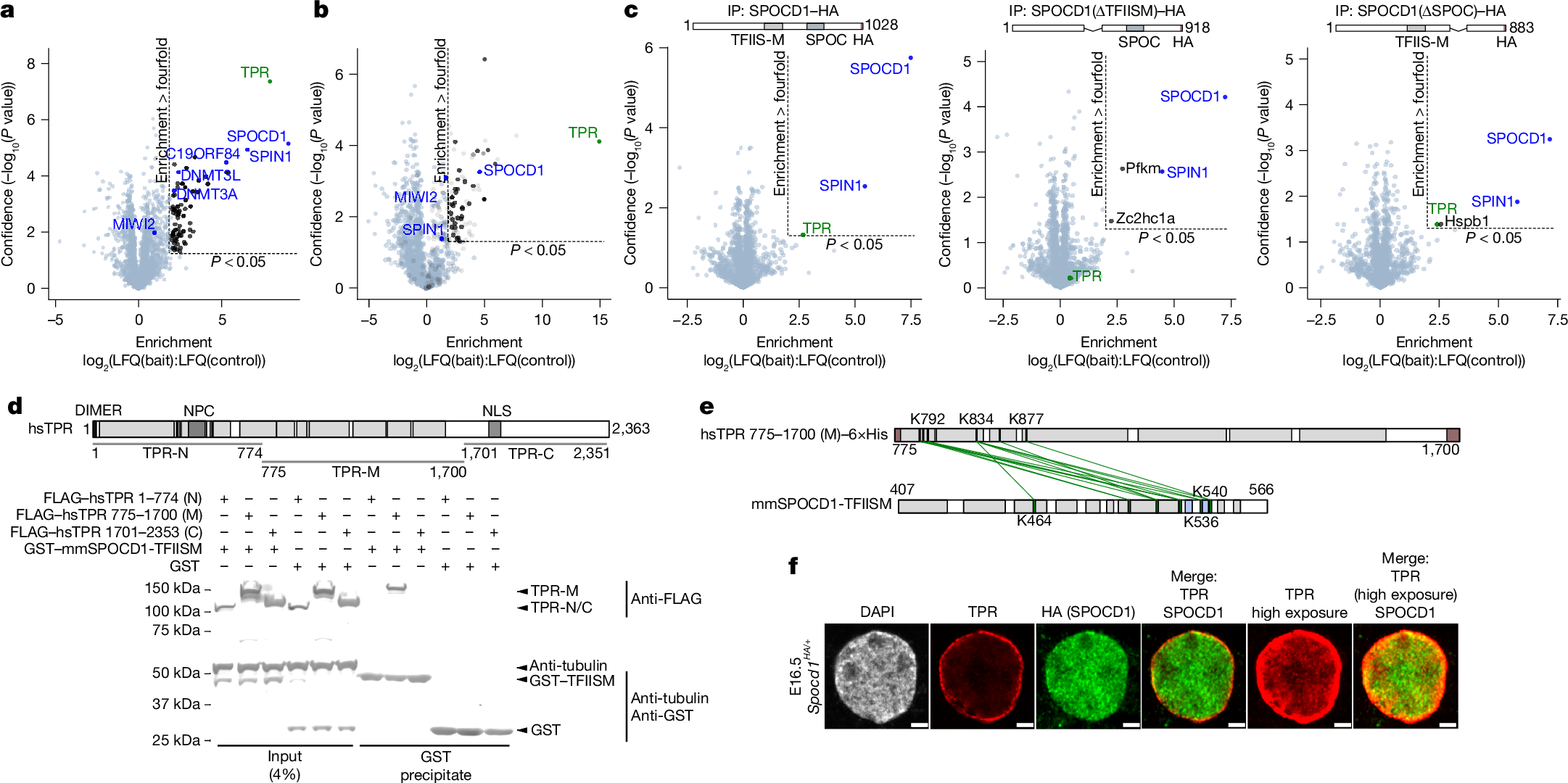

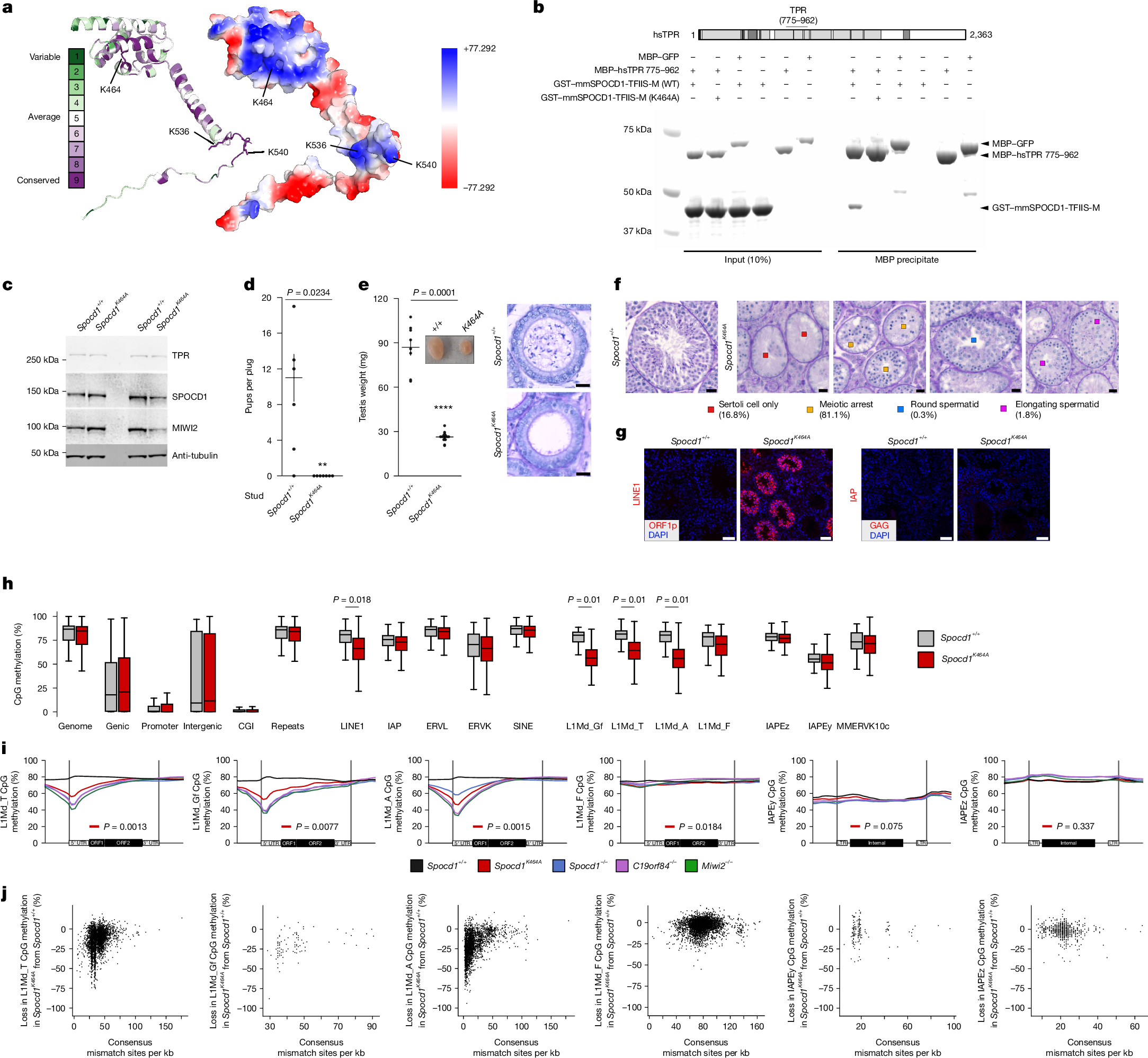

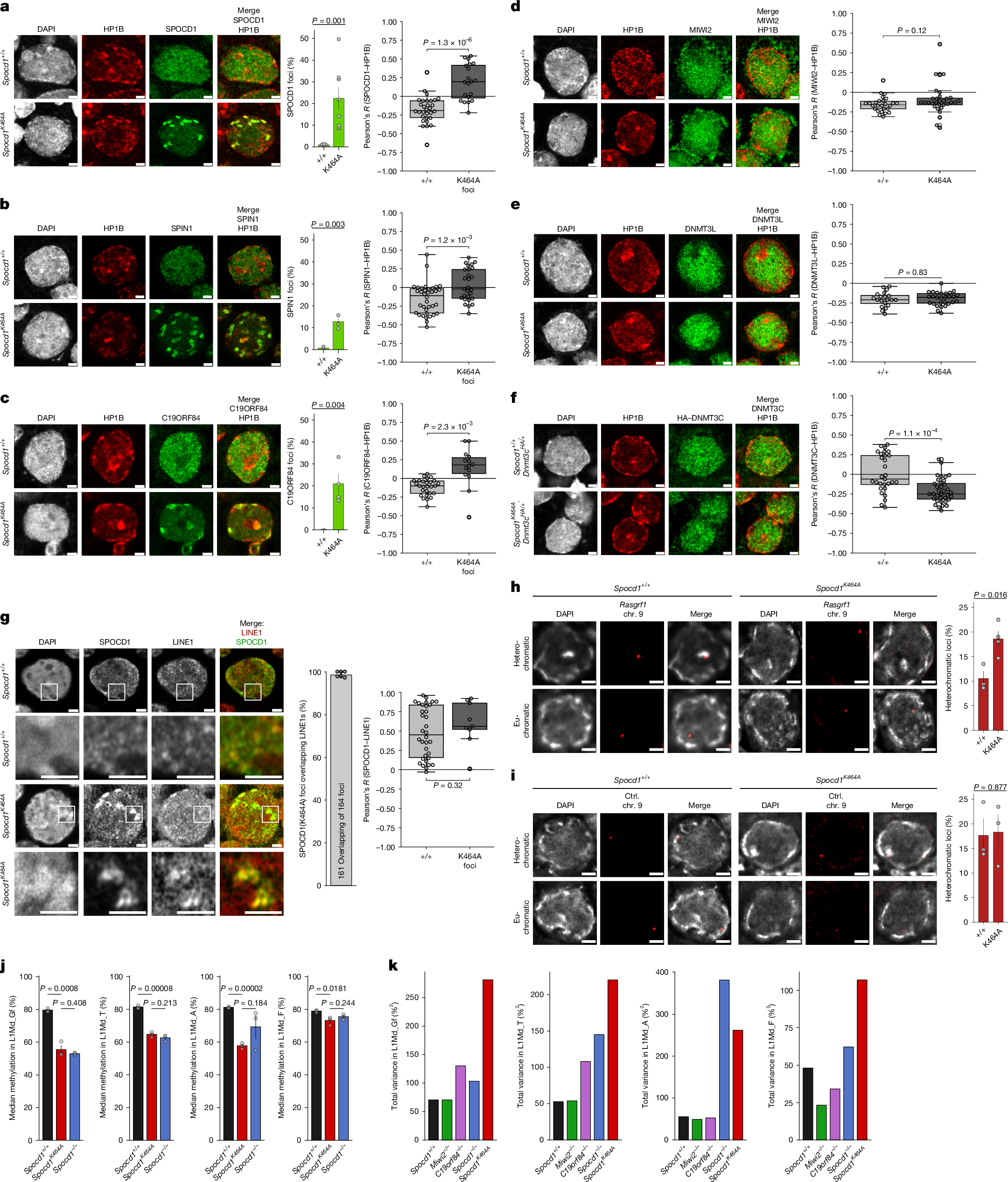

The mouse PIWI-interacting RNA (piRNA) pathway provides sustained anti-transposon immunity to the developing male germline by directing transposon DNA methylation1,2,3. The first step in this process is the recruitment of SPOCD1 to young LINE1 loci4. Thereafter, piRNA-mediated tethering of the PIWI protein MIWI2 (also known as PIWIL4) to the nascent transposon transcript recruits the DNA methylation machinery5,6. The piRNA pathway needs to methylate all active transposon copies but how this is achieved remains unknown. Here we show that nuclear piRNA and de novo methylation factors are all euchromatic, exposing constitutive heterochromatin as a genomic blind spot for the piRNA pathway. We discover a ‘nowhere-to-hide’ mechanism that enables piRNA pathway-mediated LINE1 surveillance of the entire genome. We find that SPOCD1 directly interacts with the nuclear pore component TPR, which forms heterochromatin exclusion zones adjacent to nuclear pores7. In fetal gonocytes undergoing piRNA-directed DNA methylation, TPR is found both at the nuclear periphery and throughout the nucleoplasm. We find that the SPOCD1–TPR interaction is required for complete non-stochastic piRNA-directed LINE1 methylation. The loss of the SPOCD1–TPR interaction results in a fraction of SPOCD1 and other chromatin-bound piRNA factors relocalizing to constitutive heterochromatin where they are no longer accessible to MIWI2 and the de novo methylation machinery. In summary, the piRNA pathway has co-opted TPR to guarantee that LINE1s are accessible to the piRNA and de novo methylation machineries.

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Data availability

The EM-seq data generated in this study have been deposited on ArrayExpress under the accession number E-MTAB-14862. Data for the IP–MS experiments have been deposited at ProteomeXchange under the accession number PXD060850. The CL–MS data have been deposited under PXD060851. EM-seq data for Spocd1−/− and Miwi2−/− P14 spermatogonia were retrieved from E-MTAB-7997, whereas that for C19orf84−/− spermatogonia were retrieved from E-MTAB-11612. The following Uniprot accession IDs for SPOCD1 proteins were used for conservation analyses: mouse (M. musculus, B1ASB6), golden hamster (M. auratus, A0A3Q0D6B7), Ord’s kangaroo rat (D. ordii, A0A1S3FIT4), western European hedgehog (E. europaeus, A0A1S3WPZ3), rabbit (O. cuniculus, G1SPR0), aardvark (O. afer afer, A0A8B7AXN8), bison (B. bison bison, A0A6P3HA20), bovine (B. taurus, F1MG39), goat (C. hircus, A0A452FMH8), sheep (O.aries, W5NRM3), pig (S. scrofa, F1SV96), horse (E. caballus, F6YBJ1), alpaca (V. pacos, A0A6J3AYV9), California sealion (Z. californianus, A0A6J2C2W2), northern fur seal (C. ursinus, A0A3Q7MZA7), Atlantic bottle-nosed dolphin (T. truncatus, A0A6J3PXS9), sperm whale (P. macrocephalus, A0A455B8T1), blue whale (B. musculus, A0A8B8W162), great Himalayan leaf-nosed bat (H. armiger, A0A8B7SLV8), large flying fox (P. vampyrus, A0A6P3Q928), leopard (P. pardus, A0A6P4UE11), cat (F. catus, A0A5F5XDK8), red fox (V. vulpes, A0A3Q7T0D7), dog (C. lupus familiaris, A0A8P0P5S7), polar bear (U. maritimus, A0A8M1EZU5), greater bamboo lemur (P. simus, A0A8C8YEI0), giant panda (A. melanoleuca, G1MHH0), rhesus macaque (M. mulatta, F7G2T4), northern white-cheeked gibbon (N. leucogenys, G1QNN7), Sumatran orangutan (P. abelii, H2N866), gorilla (G. gorilla gorilla, G3RKR7), chimpanzee (P. troglodytes, H2R1B9), human (H. spaiens, Q6ZMY3), American alligator (A. mississippiensis, A0A151MMW3), Chinese alligator (A. sinensis, A0A1U8CWC7), snapping turtle (C. serpentina, A0A8T1SPX3), central bearded dragon (P. vitticeps, A0A6J0UYI0), mainland tiger snake (N. scutatus, A0A6J1UEZ9), Indian cobra (N. naja, A0A8C6YBU2), American chameleon (A. carolinensis, H9GI50), western clawed frog (X. tropicalis, A0A8J0T0T7) and African clawed frog (X. laevis, A0A1L8HFK1). Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The scripts used for the EM-seq analysis are available on GitHub (https://github.com/tamchow/spocd1_pirna-directed-dna-met-variance/ (version of the record deposited on Zenodo54, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17162836) and https://github.com/rberrens/SPOCD1-piRNA_directed_DNA_met (version of the record deposited on Zenodo55, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10509247)). The Fiji/ImageJ2 plugin used to calculate Pearson’s correlation coefficients in germ cell nuclei is also available on GitHub (https://github.com/COIL-Edinburgh/ROI_NucleusColocalisation; a version of the record has been deposited on Zenodo41, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17200734).

References

Aravin, A. A., Sachidanandam, R., Girard, A., Fejes-Toth, K. & Hannon, G. J. Developmentally regulated piRNA clusters implicate MILI in transposon control. Science 316, 744–747 (2007).

Carmell, M. A. et al. MIWI2 is essential for spermatogenesis and repression of transposons in the mouse male germline. Dev. Cell 12, 503–514 (2007).

Kuramochi-Miyagawa, S. et al. DNA methylation of retrotransposon genes is regulated by Piwi family members MILI and MIWI2 in murine fetal testes. Genes Dev. 22, 908–917 (2008).

Dias Mirandela, M. et al. Two-factor authentication underpins the precision of the piRNA pathway. Nature 634, 979–985 (2024).