3D-printed low-voltage-driven ciliary hydrogel microactuators

TL;DR

Researchers developed 3D-printed hydrogel microactuators that mimic natural cilia, achieving fast 3D bending motions at low voltages (1.5 V) without hydrolysis. These microcilia enable programmable fluid manipulation and particle transport at microscale, with durability over 330,000 cycles.

Key Takeaways

- •3D-printed hydrogel microactuators replicate natural cilia motions using low-voltage electrical stimuli (1.5 V) without hydrolysis, enabling fast 3D bending at up to 40 Hz.

- •The microcilia are fabricated via two-photon polymerization, creating nanoscale pores that enhance ion migration for rapid actuation within milliseconds.

- •Arrays of these microcilia can be individually controlled with microelectrodes, allowing programmable fluid manipulation and particle transport in biologically relevant environments.

- •The actuators demonstrate high durability, maintaining over 70% performance after 330,000 continuous cycles, and can be integrated on flexible substrates for scalable fabrication.

Tags

Abstract

Micrometre-sized, densely packed natural cilia that perform non-reciprocal 3D motions with dynamically tunable collective patterns are crucial for biological processes such as microscale locomotion1, nutrient acquisition2, cell trafficking3,4,5 and embryonic and neurological development6,7,8. However, replicating these motions in artificial systems remains challenging given the limits of scalable, locally controllable soft-bodied actuation at the micrometre scale. Overcoming this challenge would enhance our understanding of ciliary dynamics, clarify their biological importance and enable new microscale devices and bioinspired technologies. Here we show a previously unrecognized fast electrical response of micrometre-scale hydrogels, induced by voltages down to 1.5 V without hydrolysis, with bending motions driven by ion migration across a nanometre-scale hydrogel network 3D-printed by two-photon polymerization, occurring within milliseconds. On the basis of these findings, we print gel microcilia arrays composed of a soft acrylic acid-co-acrylamide (AAc-co-AAm) hydrogel (modulus of approximately 1,000 Pa) that respond to electrical stimuli within milliseconds. Each microcilium measures 2–10 µm in diameter and 18–90 µm in height, achieving 3D rotational bending motion at up to 40 Hz, mirroring the geometry and dynamics of natural cilia. These gel microcilia maintain functionality after 330,000 continuous actuation cycles with less than 30% performance degradation. The gel microcilia arrays can be integrated on flexible polyimide substrates and fabricated at large scale using conventional lithography techniques. They also offer individual dynamic control by means of microelectrode arrays and enable fluid manipulation and particle transport at the micrometre scale.

Main

In low-Reynolds-number fluidic environments, viscous forces dominate inertial forces, leading to the evolution of micrometre-scale cilia structures capable of dynamically regulating beating patterns for efficient and adaptive swimming, locomotion and environmental manipulation9. Individual cilia generate 3D non-reciprocal motions10,11, whereas coordinated movements, such as metachronal waves1,12, enable effective fluid transport and manipulation13,14. For example, starfish larvae2, reef corals15, Paramecium16, ctenophores17,18 and Stentor coeruleus19,20 use coordinated cilia arrays for swimming, feeding predation and predator evasion. In mammals, ciliary flows support critical physiological processes21,22,23, such as neural cell maturation6,7, airway clearance24,25, reproductive cell transport3,4,5 and the establishment of embryonic asymmetry8 (Supplementary Video 1). Replicating these dynamic features in microscale artificial systems holds the potential for quantifiable assessment of the importance of ciliary motion, advancing microactuation and microrobotics technologies and enabling biomedical innovations21,22,23.

Artificial cilia have been realized across a broad range of sizes, numbers, motion degrees of freedom and dynamic performances, yet challenges persist in matching natural cilia. At the centimetre scale, sparse arrays of pneumatic cilia—typically comprising six actuators—generate 2D reprogrammable metachronal waves at approximately 0.25 Hz, but bulky cavity designs hinder further miniaturization26. At the millimetre and micrometre scales, tens of magnetic-field-actuated cilia achieve both 2D and 3D motions at frequencies up to 100 Hz; however, it is challenging to generate spatially heterogeneous, high-resolution magnetic fields to reconfigure the collective beating pattern27,28,29,30. At the micrometre scale, ultrasound-driven rigid cilia31,32 and arrays of pH-sensitive cilia comprising hundreds of actuators33 exhibit only basic mechanical actuation, with kinematics that falls short of biological performance and without dynamic reprogramming. In densely packed micrometre-scale arrays, light-responsive liquid-crystal cilia enable individually addressable bending and twisting and survive 100 cycles without damage. However, the slow actuation (about 0.1 Hz) limits the fluid-pumping capability and their coordinated motion requires several light sources, complicating integration and control34,35. Electrostatically actuated microsystems incorporating hundreds of cilia enable 2D motions at around 200 Hz in non-conductive high-strength dielectric liquids but are incompatible with ionic solutions, thereby restricting their applicability in biologically relevant environments36. Electrochemically redox-driven thin-film cilia, fabricated at both millimetre and micrometre scales in hundreds, are limited to 2D motions at frequencies between 5 and 100 Hz and are only tested around 1,000 cycles, as repeated redox may degrade the actuators37,38. Although some cilia systems use soft substrates to improve compliance28,29,30,37, most use rigid platforms, which are less conformable. Altogether, constraints in miniaturization, fast dynamics, motion degrees of freedom, scalable fabrication and actuator durability highlight the need for artificial cilia comparable with their biological counterparts.

Hydrogel microactuator fabrication

In this study, we use two-photon polymerization (TPP) for 3D printing and tune its key processing parameters, such as slicing and hatching (Extended Data Fig. 1a (ii)), to reduce the pore size of the ionic hydrogel from tens of micrometres in conventional millimetre hydrogel actuators (Extended Data Fig. 1b (i)) to the nanometre scale (transmission electron microscopy (TEM) image shown in Fig. 1a (1)). This nanoscale porosity increases the effective surface area and expands the capacity of the electric double layer (EDL), thereby enhancing ion transport and electro-osmotic flow in ionic solutions39,40,41 (bottom image in Fig. 1a (1)).

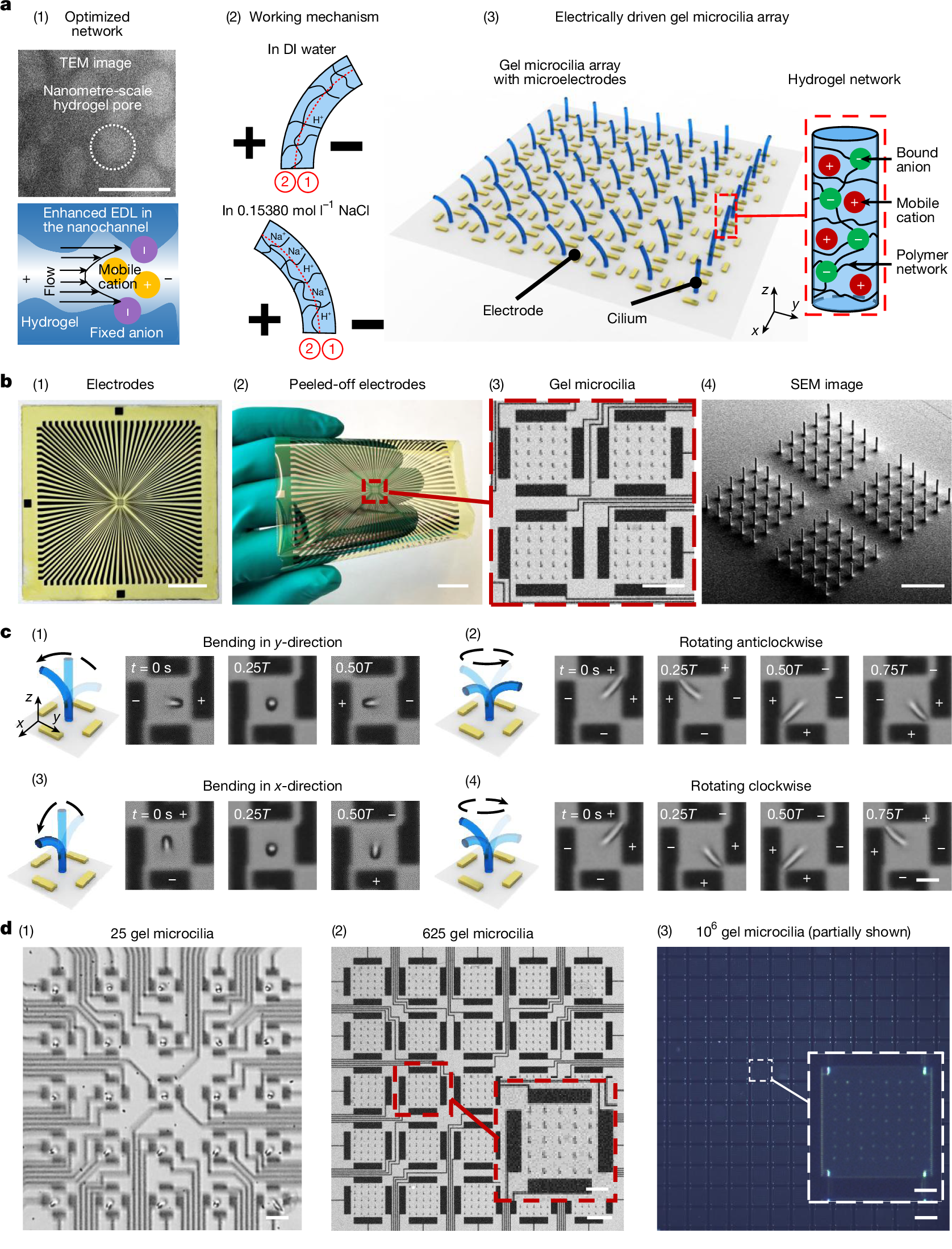

a, (1) Optimization of hydrogel pore size at the nanometre scale using TPP-based 3D printing. Top, TEM image of the 3D-printed hydrogel. Bottom, schematic showing enhanced ion flux and flow from increased EDL overlap in a nanometre-scale hydrogel channel under an electric field. (2) Working mechanism of the hydrogel microactuator. The hydrogel network is divided into region 1 (near the cathode) and region 2 (near the anode). In DI water, dissociated H+ ions from the –COOH groups dominate. Under an electric field, concentrated H+ in region 1 convert fixed –COO− groups to –COOH, reducing repulsion and shrinking the network, bending the microactuator towards the cathode. In physiological saline, Na+ ions dominate; concentrated Na+ in region 1 attracts water, swelling the network and bending towards the anode. (3) Schematic of the electrically driven gel microcilia array and AAc-co-AAm hydrogel network structure. b, Gel microcilia array on a polyimide-based microelectrode substrate. (1) Microelectrodes on glass. (2) Flexible substrate with microelectrodes on a human hand. (3) Gel microcilia array composed of four actuation cells, with each cell surrounded by four electrodes. (4) SEM image of the gel microcilia. c, Kinematics of a gel cilium in physiological saline (diameter 2 µm, height 18 µm; 5 Hz). The electrode polarity is marked by + and −. (1) Unidirectional bending along the y-direction. (2) Non-reciprocal 3D anticlockwise rotation. (3) Unidirectional bending along the x-direction. (4) Non-reciprocal 3D clockwise rotation. T denotes one motion cycle. d, Main devices used in this work. (1) 25 gel microcilia (cilium diameter 10 µm, height 90 µm). Each cilium has four surrounding electrodes for individual control. (2) 625 gel microcilia (cilium diameter 10 µm, height 90 µm). Each actuation cell with 25 cilia exhibits synchronized motion (inset, one cell). (3) 106 gel microcilia fabricated by micromoulding, partially shown in this image (cilium diameter 5 µm, height 35 µm; inset, one cell). Scale bars, 100 nm (a (1)); 2 cm (b (1), (2)); 200 µm (b (3), (4)); 6 µm (c (4)); 40 µm (d (1)); 200 µm (d (2)); 100 µm (d (2) inset); 300 µm (d (3)); 60 µm (d (3) inset).

We use this direct miniature hydrogel actuator printing technique to fabricate AAc-co-AAm gel microcilia (2–10 µm in diameter and 18–90 µm in height) with the microelectrodes placed around them (Extended Data Figs. 2 and 3). Under 1.5-V potential, which is below the threshold for electrolysis reactions (≤1.5 V), these closely spaced 30–300-µm electrodes generate electric fields ranging from 5,000 V m−1 to 50,000 V m−1. Figure 1a (2) depicts the bending mechanism. In deionized (DI) water, dissociated H+ ions from carboxylic acid groups migrate and accumulate in region 1, causing the hydrogel to shrink in this region and bend towards the cathode. By contrast, in physiological saline (0.15380 mol l−1 NaCl), dominant Na+ ions draw water molecules into region 1, swelling the hydrogel and bending it towards the anode. This ion-migration-induced dynamic motion can mimic the 3D rotation, reconfiguration and localized heterogeneous behaviour observed in mouse embryonic node cilia8 (Extended Data Fig. 4, Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Videos 1–4). Figure 1a (3) illustrates the configuration of an AAc-co-AAm hydrogel microcilia array with the integrated microelectrodes around them. Details of the fast bending mechanism of the gel microcilia are discussed in the next section.

Figure 1b shows that the gel microcilia array can be fabricated on a flexible polyimide-based microelectrode substrate. Electrical signals within one actuation cell (four electrodes around it) can actuate the central gel cilium to generate reprogrammable 3D bending motions (Supplementary Video 5). When in physiological saline, activating the left and right electrodes can bend the cilium in the y-direction (Fig. 1c (1)) and activating the top and bottom electrodes causes bending in the x-direction (Fig. 1c (3)). Furthermore, rhythmic electrode cycling can generate rotating electric fields, enabling anticlockwise (Fig. 1c (2)) or clockwise rotation (Fig. 1c (4)). Finally, many such gel microcilia, each with independently controlled electrodes, can form a programmable hydrogel cilia surface. Such an approach can be demonstrated by an array of 25 individually controlled gel microcilia (Fig. 1d (1)), an array of 625 gel microcilia (Fig. 1d (2)) or an array of 106 gel microcilia (Fig. 1d (3)).

Fast bending mechanism

Previously reported millimetre-scale hydrogels are actuated through interfacial pH or osmotic gradients42,43,44. By contrast, the micrometre-scale hydrogels reported here are actuated through internal ion migration by means of nanometre-scale pores, resulting in distinct bending behaviour and a 100-fold increase in bending speed response (Extended Data Figs. 5 and 6 and Supplementary Videos 6 and 7). This section will first explain the bending mechanism, particularly bending direction and bending amplitude, and then the fundamental reason for fast bending dynamics of the proposed hydrogel.

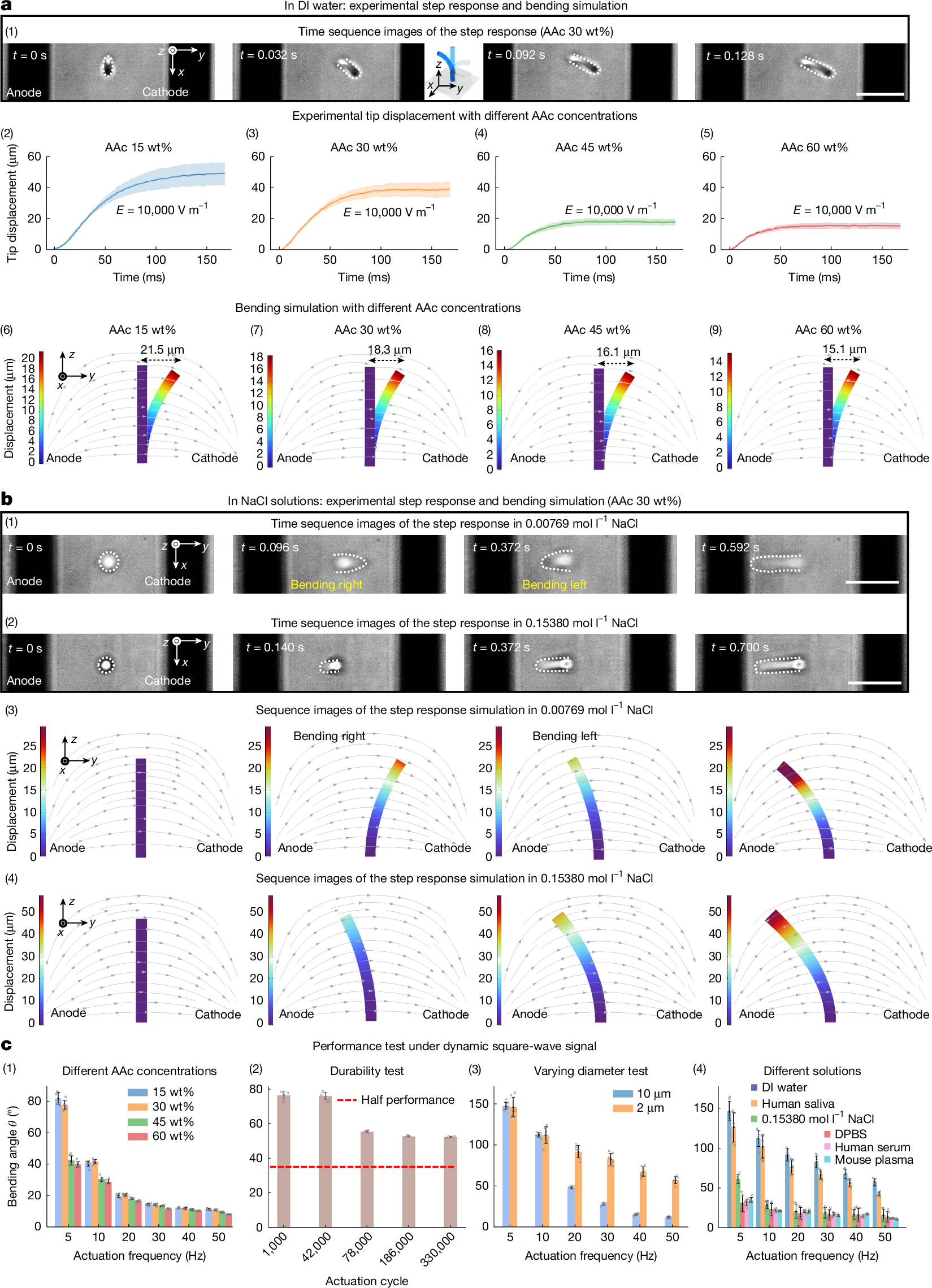

In this study, the gel microcilia exhibit different bending directions in solutions with different NaCl concentrations. In H+-dominated DI water, they bend towards the cathode (Fig. 2a (1) and Supplementary Videos 8 and 9). In Na+-dominated physiological saline (0.15380 mol l−1 NaCl), they bend oppositely towards the anode (Fig. 2b (2) and Supplementary Video 8). At an intermediate concentration (0.00769 mol l−1 NaCl), competitive H+/Na+ effects cause transient cathode bending followed by anode reversal (Fig. 2b (1) and Supplementary Video 8).

a, Step response of gel microcilia in experiments and corresponding bending simulations in DI water. (1) Time sequence of 30 wt% AAc gel microcilia bending in DI water with the left electrode as the anode and the right electrode as the cathode; dashed lines highlight cilia outlines. Under the field, cilia bend towards the cathode owing to H+ accumulation on the right side (region 1 in Fig. 1a (2)). (2)–(5) Experimental tip displacement at different AAc concentrations shows reduced bending with higher AAc content (mean ± s.d.; n = 6 samples). (6)–(9) Simulated bending for varying AAc content reproduces the same trend, with displacement decreasing from 21.5 µm to 15.1 µm. b, Step response and simulations in NaCl solutions. (1) In 0.00769 mol l−1 NaCl, cilia first bend towards the cathode as fast H+ ions shrink the right side and then reverse towards the anode as slower Na+ ion swelling dominates on the right side. (2) In 0.15380 mol l−1 NaCl, bending occurs only towards the anode. (3), (4) Simulations reproduce these bending behaviours in NaCl solutions. c, Influence of different factors on dynamic performance under a square-wave signal. (1) AAc concentration: lower AAc content enhances bending (mean ± s.d.; n = 6 samples). (2) Actuation cycle: the gel microcilia maintained a bending angle of 50° after 330,000 continuous actuation cycles, corresponding to 70% of the initial performance, and then stabilize (mean ± s.d.; n = 4 samples). (3) Cilium diameter: 2-µm actuators outperform 10-µm actuators at high frequencies (mean ± s.d.; n = 6 samples). (4) Solution type: gel microcilia tested in DI water, physiological saline, DPBS, human saliva, serum and mouse plasma (mean ± s.d.; n = 6 samples for DI and n = 5 samples for the others). Scale bars, 100 µm (a (1)); 100 µm (b (1), (2)). All of the characterization experiment details are provided in Supplementary Note 7.

The bending direction can be explained by internal ion migration. In the H+-dominated DI water, the H+ ions from carboxylic acid groups migrate under an electric field and accumulate in the hydrogel network region 1 (ref. 45) (Fig. 1a (2)), causing local shrinkage and bending the gel microcilia towards the cathode. The AAc-co-AAm hydrogel is a pH-sensitive hydrogel that will shrink in acidic environments. The elevated H+ concentration in low-pH conditions converts some fixed –COO− groups to –COOH, reducing repulsive forces in the hydrogel network and causing the hydrogel to shrink42,46. Consequently, the gel microcilia bend towards the cathode in DI water owing to H+ ion migration inside the hydrogel, whereas the previous millimetre hydrogel bends towards the anode owing to interfacial pH gradients42,43,44 (Fig.