PAF15–PCNA exhaustion governs the strand-specific control of DNA replication

TL;DR

Excessive origin firing during DNA replication saturates chromatin-bound PCNA, restricting lagging-strand synthesis. PAF15 emerges as a dosage-sensitive regulator that binds PCNA specifically on the lagging strand, protecting it from premature unloading. When PAF15-PCNA assemblies are exhausted, the S-phase checkpoint globally restricts origin activation.

Key Takeaways

- •Excessive origin firing saturates chromatin-bound PCNA, limiting further PCNA loading and lagging-strand synthesis.

- •PAF15 is a dosage-sensitive regulator that binds PCNA specifically on the lagging strand via a high-affinity PIP motif.

- •PAF15 occupies PCNA's DNA-encircling channel, protecting the clamp from premature unloading by the ATAD5–RFC complex.

- •Timeless–Claspin blocks PAF15–PCNA binding on the leading strand, preventing detrimental effects on replisome progression.

- •E2F4-mediated repression fine-tunes PAF15 expression to ensure optimal dosage and strand specificity.

Tags

Abstract

Eukaryotic genome replication is surveyed by the S-phase checkpoint, which coordinates sequential origin activation to prevent the exhaustion of poorly defined, rate-limiting replisome components1,2,3. Here we show that excessive origin firing saturates chromatin-bound proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA)—a sliding clamp for DNA polymerase processivity and Okazaki fragment processing4—thereby restricting further PCNA loading and lagging-strand synthesis when checkpoint control is lost. PCNA-associated factor 15 (PAF15) emerges as a dosage-sensitive regulator of this process5,6,7,8,9. During unperturbed S phase, the entire soluble PAF15 pool binds to chromatin, leaving no reserve to stabilize PCNA under conditions of excessive origin activation. PAF15 binds to PCNA specifically on the lagging strand through a high-affinity PIP motif and occupies the DNA-encircling channel, protecting the clamp and associated enzymes from premature unloading by the ATAD5–RFC complex. Conversely, overexpression of PAF15 or forced redistribution to the leading strand disrupts replisome progression and induces cell death. These detrimental effects are mitigated by Timeless–Claspin, which blocks PAF15–PCNA binding on the leading strand. E2F4-mediated repression fine-tunes PAF15 expression to ensure optimal dosage and strand specificity. These findings reveal a previously unrecognized replisome constraint: when PAF15–PCNA assemblies are exhausted, the S-phase checkpoint globally restricts origin activation, linking a strand-specific rate-limiting mechanism to global replication dynamics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Timely lagging strand maturation relies on Ubp10 deubiquitylase-mediated PCNA dissociation from replicating chromatin

Fast and efficient DNA replication with purified human proteins

Structures of the human leading strand Polε–PCNA holoenzyme

Main

Error-free genome duplication is essential for precise genetic inheritance and for protection against genomic instability—a driver of oncogenic transformation and cancer progression10,11. In eukaryotes, such precision is maintained by two fundamental controls: the number of active replication origins and the velocity of active replisomes12,13. The DNA replication program is established in G1 by the licensing of an excess pool of origins, marked by the loading of inactive minichromosome maintenance (MCM) helicases 2–7 onto chromatin. During S phase, only around 10% of these origins are activated to form active replisomes, in which MCM2–MCM7 assemble with CDC45 and GINS1–GINS4 (Go-Ichi-Ni-San 1–4 subunits) to form the CMG helicase, together with DNA polymerases and additional regulatory proteins14. The S-phase checkpoint, governed by the ataxia telangiectasia and RAD3-related (ATR) pathway, coordinates origin firing with ongoing synthesis in cells both in unperturbed S phase and under replication stress, thereby preventing premature or excessive origin activation and untimely mitotic entry1,15. Whereas insufficient origin activation causes DNA under-replication16, excessive origin firing exhausts replication resources and destabilizes the genome2,3. Thus, we hypothesize that the S-phase checkpoint operates within boundaries set by as-yet-unidentified replisome dynamics that define a global replication capacity and prevent replication from exceeding this threshold.

Unscheduled origin activation affects DNA replication

To test this hypothesis, we examined whether rapid origin firing would deplete core replisome components and thereby reveal the key rate-limiting steps of global genome replication. Therefore, we applied brief ATR inhibition to induce rapid and aberrant cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) activation in a cell line expressing a TagRFP chromobody targeting endogenous PCNA, a proxy for active replisomes and local replication dynamics17 (Fig. 1a). Using quantitative image-based cytometry (QIBC)2,18, we first confirmed that short-term inhibition of ATR (40 min) robustly activates CDKs during S phase, as indicated by phosphorylation of FOXM1—an established CDK1 and CDK2 (hereafter, CDK1/2) target1—without triggering a DNA damage response, as evidenced by the absence of pan-nuclear γH2AX (phosphorylated histone H2AX) (Fig. 1a, Extended Data Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 1a,b). As anticipated19, such ATR inhibition led to a pronounced increase in active fork density (Extended Data Fig. 1b) and a corresponding reduction in replication fork speed (Extended Data Fig. 1c). However, despite increased CDK activity and abrupt activation of new origins, we did not observe an increase in PCNA chromobody foci after ATR inhibition, as assessed through QIBC of a fixed cell population and live-cell tracking (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 1c).

a, Left, workflow using U2OS cells stably expressing the PCNA TagRFP chromobody. Scale bar, 10 µm. ATRi, ATR inhibitor; IF, immunofluorescence; pFOXM1, FOXM1 phosphorylated at Thr600. Middle, QIBC of pFOXM1 in cells treated with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or exposed to ATRi for the indicated durations. Nuclear DNA was counterstained with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole), and total DAPI intensity was used to infer DNA content (2n, G1; 4n, G2). n > 8,000 cells per condition. The colour gradient denotes mean PCNA TagRFP chromobody intensity in individual nuclei. a.u., arbitrary units. Right, fold change in CDK1/2 activity (pFOXM1 intensity) and number of PCNA chromobody spots, normalized to the DMSO-treated condition. b, Left, workflow. Middle, three-dimensional confocal images of endogenously tagged CDC45–GFP U2OS cells immunostained for PCNA. Scale bars, 10 µm. Right, intensity profiles from the insets for CDC45–GFP (green) and PCNA (red) within replication foci. c,d, QIBC of CDC45, PCNA (c) and DNA ligase 1 (d) chromatin binding (n > 5,000 cells). Pink dotted lines in the scatter plots denote approximate upper limits of chromatin-bound protein levels. Fold changes in S-phase-specific chromatin association are shown. e,f, QIBC of RPA1 and γH2AX (e), and of RPA1 and PCNA (f), in U2OS cells under the indicated conditions (n > 8,000 cells). The dotted line marks the onset of replication catastrophe. ssDNA, single-stranded DNA. g, Fold change on chromatin for the indicated proteins during ATRi treatment relative to DMSO (from data in Supplementary Fig. 2d,e). h, Western blot of chromatin from U2OS cells treated with the indicated short interfering RNAs (siRNAs) for 48 h. siATAD5, ATAD5 siRNAl; siRFC1, RFC1 siRNA. i, QIBC of chromatin-bound RPA1 and γH2AX in control or ATAD5-depleted U2OS cells treated with hydroxyurea (HU) or ATRi. The colour gradient reflects the PCNA chromatin-bound intensity. The dotted line marks the onset of replication catastrophe; the red boxes indicate cells undergoing catastrophe (n > 10,000 cells). The QIBC plots shown are representative of at least two independent biological replicates. The camera icon in a was created with BioRender.com. Somyajit, K. (2025) https://BioRender.com/ergwc0j.

Independent to the PCNA chromobody-specific readout, anti-PCNA immunostaining yielded identical results (Fig. 1b,c and Supplementary Fig. 1d). ATR inhibition led to a robust focal chromatin accumulation of early replisome components—including CDC45 of the CMG complex, the replicative DNA polymerases and the replication progression complex (RPC) factors Timeless and Claspin (Extended Data Fig. 1d). However, chromatin-bound PCNA showed only a modest (1.2-fold) increase, and did not scale with CDC45, which rose by 3.6-fold (Fig. 1b,c).

PCNA, a highly abundant homotrimeric sliding clamp, acts as a structural scaffold for continuous leading-strand synthesis by POLε20, and coordinates the dynamic interplay among POLδ, FEN1 and DNA ligase 1 for the synthesis and maturation of short Okazaki fragments (OkFs)21,22. Notably, although core and leading-strand-specific factors were enriched on S-phase chromatin (Extended Data Fig. 1d), further analysis revealed that lagging-strand processes that depend on PCNA—such as those involving FEN1 and DNA ligase 1—did not increase and were instead mildly diminished on chromatin during excess origin activation (Fig. 1d and Extended Data Fig. 1e). PCNA also orchestrates epigenome maintenance by recruiting DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1) to post-replicative nascent DNA23. Of note, the depletion of PCNA and lagging-strand factors from the chromatin pool was accompanied by a failure to load additional DNMT1 onto S-phase chromatin after ATR inhibition (Extended Data Fig. 1f), further highlighting a unique chromatin-level paucity of PCNA induced by unscheduled origin firing.

The functional exhaustion of OkF processing after ATR inhibition was confirmed using proximity ligation assay (PLA)–QIBC, which revealed reduced interactions between PCNA and DNA ligase 1 (Extended Data Fig. 1g), despite increased Timeless–RPA2 proximity in new replisomes (Extended Data Fig. 1g, right). Moreover, these results were corroborated by chromatin fractionation immunoblotting (Extended Data Fig. 1h,i) and QIBC across two additional cell lines (Extended Data Fig. 1j). Finally, the findings obtained using an ATR inhibitor were recapitulated by both WEE1 inhibition and Claspin depletion, both of which enhance CDK activity and are known to promote aberrant origin firing (Supplementary Fig. 2a–c).

Unligated OkFs are processed through a non-canonical pathway, which is mediated by PARP124. This is evidenced by the accumulation of nascent, S-phase-specific polyADP-ribosylation (PAR) chains after short-term inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase (PARG)24 (Extended Data Fig. 2a). Consistent with our observation that PCNA lagging-strand activities are depleted by excessive origin firing (Fig. 1c,d), even under normal replication conditions, inhibition of PARG triggered a rapid accumulation of PAR chains specifically in S phase (Extended Data Fig. 2b). This effect intensified with acute inhibition of ATR, but was completely suppressed by blocking dormant origin firing (Extended Data Fig. 2b), indicating that unresolved lagging-strand intermediates after excessive origin firing drive the early activation of PARP1, before fork collapse (40 min of ATR inhibition). The essentiality of this non-canonical pathway is underscored by the fact that PARP1 inhibition and ATR or WEE1 inhibition are synthetic lethal (Extended Data Fig. 2c,d).

Premature origin firing and DNA replication stress have a catastrophic effect on the replicating genome, collectively known as ‘replication catastrophe’25. Exhaustion of the available pool of genome-protective RPA protein marks the onset of such terminal replication collapse, especially when checkpoint failure coincides with DNA replication stress induced by hydroxyurea-triggered nucleotide depletion2 (Fig. 1e). In light of our new findings, we compared the rate of RPA exhaustion with the chromatin paucity of PCNA. Notably, chromatin-bound PCNA and DNA ligase 1 were already saturated—or declined—before RPA exhaustion under hydroxyurea plus ATR inhibition (Fig. 1f and Extended Data Fig. 2e), suggesting that a loss of core replisome activity precedes RPA depletion in driving replication catastrophe.

Together, these results reinforce the notion that PCNA and lagging-strand processes undergo functional exhaustion during unperturbed origin activation and become further depleted upon unscheduled origin firing.

Mechanism of chromatin-level PCNA depletion

To delve deeper, we combined mass spectrometry (MS) with TurboID-based biotinylation of PCNA-proximal proteins (Extended Data Fig. 2f–h) to identify factors that might influence its rate-limiting mechanisms. We focused on PCNA loaders, including canonical replication factor C 1–5 (RFC1–RFC5) and the CTF18-RFC variant—which encircle PCNA homotrimers on the lagging and on the leading strands, respectively4,26—and PCNA-associated factor 15 (PAF15, also known as PCLAF). PAF15 contains a high-affinity PCNA-interacting peptide (PIP) motif and has been implicated in restraining error-prone DNA polymerases during DNA damage5,6,7,8,27, as well as regulating DNMT1 chromatin association through dual mono-ubiquitination of Lys15 and Lys24 by the E3 ligase UHRF128. However, the direct role of PAF15 in unperturbed DNA replication remains unknown.

Mapping the dynamic range of origin activation after ATR inhibition, QIBC analysis revealed that PCNA—and its associated factor DNA ligase 1—accumulate on chromatin by no more than 1.3-fold, even as new origins continue to fire over a 60–90-min window, as evidenced by increasing levels of chromatin-bound Timeless and RPA (Fig. 1g and Supplementary Fig. 2d). Whereas the leading-strand PCNA loader CTF18 accumulated on replicating chromatin, RFC1—of the canonical RFC complex—showed only limited recruitment, revealing a bottleneck in PCNA loading during excessive origin activation, consistent with recent reports of RFC1 depletion under replication stress and checkpoint loss29,30. Notably, PAF15 showed chromatin accumulation closely mirroring that of PCNA after ATR inhibition (Fig. 1g and Supplementary Fig. 2e), raising the possibility that its natural depletion exposes a rate-limiting control point for PCNA function after chromatin loading, particularly in the context of strand-specific DNA replication dynamics.

In line with this, depletion of the PCNA unloader ATAD531, which stabilizes PCNA, OkF processing factors and PAF15 on chromatin (Fig. 1h and Extended Data Fig. 2i–k), rescued replication catastrophe by preventing the loss of PCNA and DNA ligase 1 during excess origin firing (Fig. 1i and Extended Data Fig. 2l). These findings suggest that continuous PCNA unloading under excessive origin activation leads to chromatin depletion of PCNA, whereas exhaustion of key regulators such as PAF15 imposes a rate-limiting control.

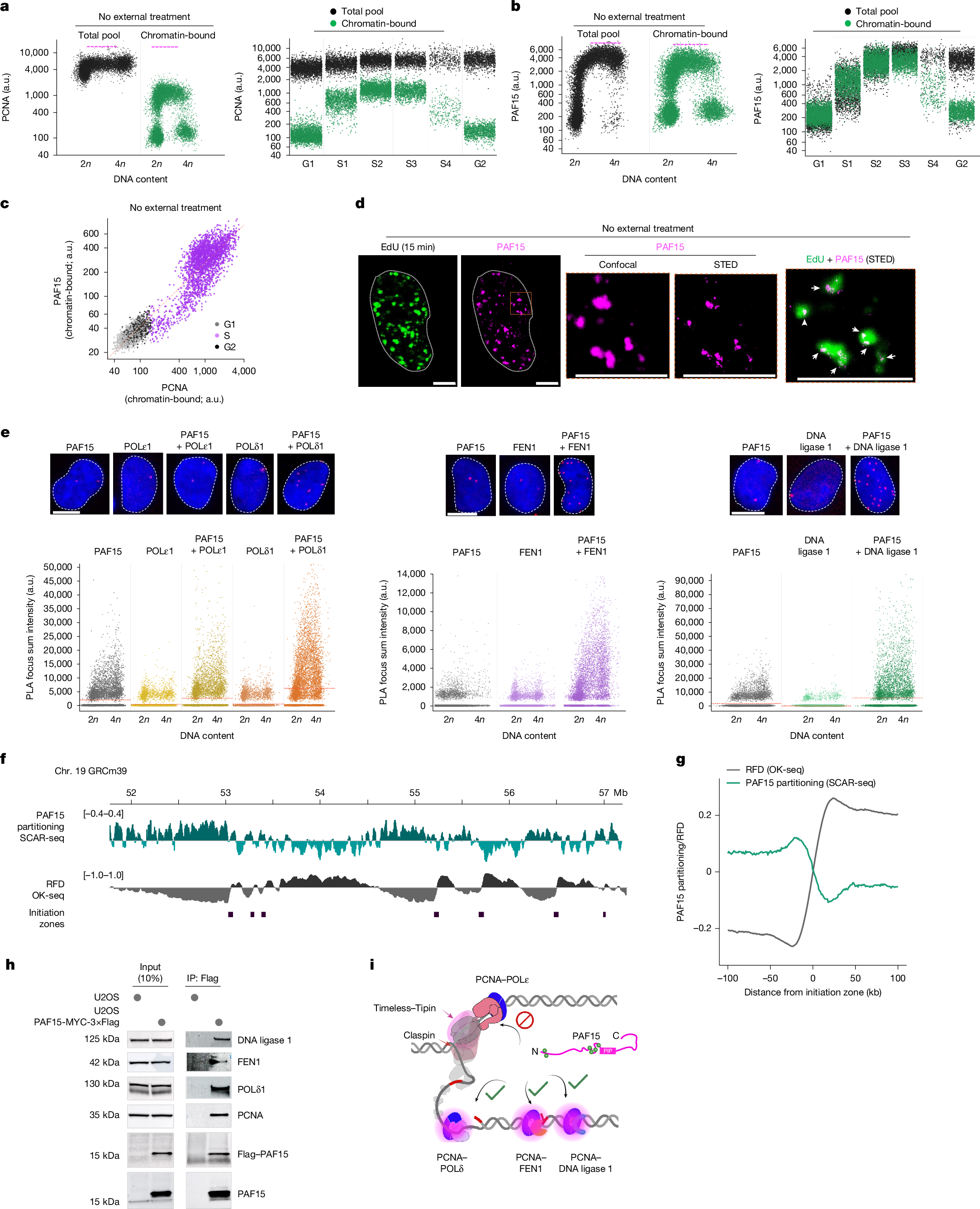

PAF15 controls PCNA during lagging-strand maturation

We next examined whether chromatin-bound PCNA dynamics depend on the natural paucity of soluble PCNA-associated factors such as PAF15. Quantitative, cell-cycle-resolved comparison of total and chromatin-bound pools showed that whereas PCNA and its effectors—including DNA ligase 1, DNA polymerases and CTF18—remained abundant, RFC1 exhibited notable paucity in total levels29,30 (Fig. 2a, Extended Data Fig. 3a–e and Supplementary Fig. 3a). PAF15 was almost entirely chromatin-bound, with negligible soluble excess during normal origin firing (Fig. 2b), and this was consistent across cell types, antibodies and synchronization assays (Extended Data Fig. 3f–i).