Cholinergic modulation of dopamine release drives effortful behaviour

TL;DR

Effort increases dopamine release for rewards via acetylcholine modulation in the nucleus accumbens. Blocking this cholinergic effect impairs effortful behavior without affecting low-effort rewards.

Key Takeaways

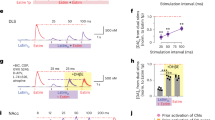

- •Effort amplifies dopamine response to rewards through local acetylcholine release in the nucleus accumbens.

- •Acetylcholine binds to nicotinic receptors on dopamine axon terminals to enhance dopamine release in high-effort contexts.

- •Blocking cholinergic modulation reduces dopamine release selectively during high-effort tasks, impairing effortful behavior.

- •This mechanism reconciles in vitro and in vivo studies by showing context-dependent acetylcholine-dopamine interactions.

- •Effort encoding in dopamine release is partially independent of dopamine cell body activity in the ventral tegmental area.

Tags

Abstract

Effort is costly: given a choice, we tend to avoid it1. However, in many cases, effort adds value to the ensuing rewards2. From ants3 to humans4, individuals prefer rewards that had been harder to achieve. This counterintuitive process may promote reward seeking even in resource-poor environments, thus enhancing evolutionary fitness5. Despite its ubiquity, the neural mechanisms supporting this behavioural effect are poorly understood. Here we show that effort amplifies the dopamine response to an otherwise identical reward, and this amplification depends on local modulation of dopamine axons by acetylcholine. High-effort rewards evoke rapid acetylcholine release from local interneurons in the nucleus accumbens. Acetylcholine then binds to nicotinic receptors on dopamine axon terminals to augment dopamine release when reward is delivered. Blocking the cholinergic modulation blunts dopamine release selectively in high-effort contexts, impairing effortful behaviour while leaving low-effort reward consumption intact. These results reconcile in vitro studies, which have long demonstrated that acetylcholine can trigger dopamine release directly through dopamine axons6,7,8,9,10,11, with in vivo studies that failed to observe such modulation12,13,14, but did not examine high-effort contexts. Our findings uncover a mechanism that drives effortful behaviour through context-dependent local interactions between acetylcholine and dopamine axons.

Similar content being viewed by others

Cholinergic modulation enables scalable action selection learning in a computational model of the striatum

Acetylcholine waves and dopamine release in the striatum

An axonal brake on striatal dopamine output by cholinergic interneurons

Main

Reward delivery evokes a burst of dopamine (DA) release in the nucleus accumbens (NAc), helping to promote reward-seeking behaviours15,16. The amplitude of this DA burst integrates multiple attributes of the reward, including both the size of the reward and how much effort went into it17,18,19. Although DA release is largely driven by the firing of DA neurons in the midbrain, studies have proposed a key role for local modulation of DA axon terminals in the striatum as well20,21,22,23. Which patterns of DA release are behaviourally relevant, what inputs determine these patterns and whether these inputs dissociate DA cell body activity from striatal DA release are all subject to debate24,25,26.

Recently, we have found that DA release scales with preceding effort even if DA axon terminals in the NAc are stimulated directly via optogenetics17. When mice work for an identical optogenetic stimulation, more effort leads to more DA release. We reasoned that this variability in DA release might result from local modulation of DA axon terminals, a phenomenon that has been studied at length in vitro20,21,22,23 but has proven more difficult to isolate in vivo. Of the many modulators with potential to calibrate DA release, acetylcholine (ACh) consistently emerges as a potent effector, although the nature of this interaction has been contested6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,27. In particular, there is ongoing debate over whether cholinergic interneurons in the striatum, which are capable of eliciting axonal DA release independent of DA cell body activity6,7,8,9,10,11, actually do so in any behavioural context12,13,14.

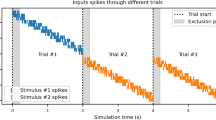

Reward-evoked DA release encodes expended effort

To discover how reward-evoked DA release is modulated by effort, we used a behavioural task17 that varies effort requirements for the same reward (Fig. 1a,b). Mice were first trained to nose poke during fixed ratio 1 (FR1) and FR5 schedules of reinforcement for sucrose reward. Once they achieved accurate and stable responding, mice proceeded to a task in which effort was varied through descending 10-min FR blocks. Mice performed the task well, with very few inactive pokes (Extended Data Fig. 1a) and consistent behaviour from day to day (Extended Data Fig. 1b,c). As the effort requirement increased, mice modulated their performance in the expected ways, initially escalating their poking rates to maintain a high level of reward consumption before reducing their poking rates and reward earnings (Extended Data Fig. 1d,e). Compared with low-effort rewards, rewards delivered after high effort were retrieved more quickly and consistently, suggesting high task engagement (Extended Data Fig. 1f,g).

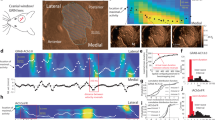

a, Schematic of the effort task for the sucrose reward and a representative image of GRAB DA recording. Scale bar, 100 µm. ac, anterior commissure. Schematic was adapted with permission from ref. 63, Elsevier. b, Operant training schedule (top), task structure for obtaining rewards in the effort task (bottom left) and within-session schedule of effort blocks (bottom right). Mice worked for rewards in 10-min blocks of FR46, FR21, FR10, FR5 and FR1. CS, conditioned stimulus. c, DA release in the NAc during the sucrose effort task aligned to the first nose poke of each trial, reward delivery and reward consumption, averaged across mice (n = 6). d, Heatmaps illustrating the GRAB DA responses for each mouse across the FR schedules in the sucrose effort task. e, Average DA release aligned to the reward delivery for each FR block in the effort task. f, DA release area under the curve (AUC; 0–4 s) for each FR in the effort task. Friedman test, Friedman statistic = 23.33, ***P = 0.0001. Peak DA release for each FR is also shown (right). Friedman test, Friedman statistic = 23.33, ***P = 0.0001. g, Schematic of the general linear model used to predict DA release dynamics in the effort task. h, Contribution of each behavioural predictor to the total model R2, assessed using tenfold cross-validation. One-way ANOVA, F(3,27) = 5,744, ****P < 0.0001. Sidak-corrected multiple comparisons: ****P < 0.0001 for active nose poke (NP) versus inactive nose poke; P = 0.12 for active nose poke versus magazine entry; ****P < 0.0001 for active nose poke versus reward delivery; ****P < 0.0001 for inactive nose poke versus magazine entry; P < 0.0001 for inactive nose poke versus reward delivery; and ****P < 0.0001 for reward delivery versus magazine entry. n = 10 iterations. i, Actual versus model-predicted GRAB DA signal for example low-effort and high-effort trials. j, Schematic of the model used to test the unique contributions of FR and ITI. k, Contribution of FR and ITI to the total model R2. Paired two-sided t-test, t = 11.39, ****P < 0.0001. n = 10 iterations. l–v, Similar to panels a–k, except for the optogenetic DA self-stimulation task. n = 8 DAT–Cre mice. Schematic in l was adapted with permission from ref. 63, Elsevier. Statistics in panel q: Friedman test, Friedman statistic = 29.10, ****P < 0.0001 (left). Friedman test, Friedman statistic = 30.50, ****P < 0.0001 (right). Statistics in panel s: one-way ANOVA, F(3,27) = 16,250, ****P < 0.0001. Sidak-corrected multiple comparisons: P < 0.0001 for active nose poke versus inactive nose poke; ****P < 0.0001 for active nose poke versus magazine entry; P < 0.0001 for active nose poke versus reward delivery; **P = 0.0025 for inactive nose poke versus magazine entry; ****P < 0.0001 for inactive nose poke versus reward delivery; and ****P < 0.0001 for reward delivery versus magazine entry. Statistics in panel v: paired two-sided t-test, t = 67.81, ****P < 0.0001. Data are mean ± s.e.m.

As mice worked for sucrose rewards, we recorded DA release in the NAc with GRAB DA (Fig. 1a). We observed robust DA release time locked to reward delivery and consumption, but not during nose pokes (Fig. 1c). Consistent with our previous findings17, DA release at the time of reward delivery scaled with FR, such that high-effort sucrose rewards evoked more DA release (Fig. 1d–f). This increase in DA release at higher FRs was not due entirely to longer intervals between rewards, because we observed similar modulation regardless of inter-trial interval (ITI; Extended Data Fig. 2a–h).

To more precisely determine what aspects of the task were encoded by DA, we trained a general linear model on various behaviours and task characteristics (kernels; Fig. 1g). The general linear model revealed a major contribution of reward delivery, but not nose pokes or magazine entries, to DA release (Fig. 1h). The model accurately predicted DA dynamics at both low and high efforts (Fig. 1i), with FR being a stronger predictor of DA release than ITI (Fig. 1j,k). We conclude that increased effort augments DA release for sucrose reward, recognizing that ‘effort’ includes not only physical exertion but also action repetition and behavioural persistence despite temporal delays.

To determine whether the effort encoding that we observed for sucrose reward generalized to other types of reinforcers, we used the same task but with optogenetic stimulation of DA axons in the NAc substituted for sucrose. DAT–Cre mice were prepared with Cre-dependent red-shifted ChRmine (rsChRmine) in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and GRAB DA and an optical fibre in the NAc (Fig. 1l). These mice were subjected to the same task structure as for sucrose reward, except now for brain stimulation reward (Fig. 1m). Mice performed accurately (Extended Data Fig. 1h) and consistently (Extended Data Fig. 1i,j), with similar effort dependence as in the sucrose task (Extended Data Fig. 1k,l). When mice nose poked for optical stimulation of DA release (5 s of 625-nm light at 20 Hz, 6 mW), DA release was again time locked to reward delivery (Fig. 1n). Our previous work17 demonstrated that mice will exert effort for a spectrum of optical stimulation parameters, ranging from 1 s to 10 s. We chose 5 s here because it evokes reliable and robust behavioural responding, but note that this stimulation does not perfectly mimic DA responses to sucrose reward.

As with sucrose, we observed that DA release scaled with effort, such that the same optogenetic stimulation led to more DA at higher FRs (Fig. 1o–q). This effect was not due to the time elapsed between rewards (Extended Data Fig. 2i–p). In addition, changes in DA release were not due to opsin desensitization or ‘run down’ of optically evoked release over time, as 50 min of regular stimulations (independent of mouse behaviour) showed similar DA release across the entire session (Extended Data Fig. 2q–u). Just as for the sucrose data, we trained a general linear model on the photometry results (Fig. 1r) and identified the same patterns: the reward delivery kernel was the major contributor to model performance (Fig. 1s), the model accurately predicted release dynamics across FRs (Fig. 1t) and FR was a stronger predictor of DA release than ITI (Fig. 1u,v). Collectively, these data replicate and extend our previous work17 and support the hypothesis that DA release encodes expended effort.

Effort encoding by NAc DA is cell body-independent

We next sought to characterize the mechanism underlying the effect of effort on DA release. Modulation of DA release could involve alterations at the level of cell bodies in the VTA, axon terminals in the NAc or a combination of the two22. Indeed, recent work has suggested that cell body and terminal activity can be dissociated in reward contexts28, although this theory remains contested29. Consistent with DA neuron recordings in monkeys18, we hypothesized that as mice exerted effort for reward, DA cell bodies would become more excitable, leading to synchronized activity and augmented DA release at the time of reward delivery. It was unclear, however, whether cell body activity would fully mimic the effort encoding that we observed in NAc DA release. To find out, we conducted simultaneous recordings of DA cell bodies, their axons in the NAc and NAc DA release, all while mice worked for sucrose reward (Fig. 2a). In all three recordings, we detected enhanced reward-evoked activity at higher FR schedules (Fig. 2b–f). However, the enhancement of DA cell body Ca2+ activity (Fig. 2c) appeared to asymptote at an earlier FR than either axon terminal Ca2+ activity (Fig. 2e) or NAc DA release (Fig. 2f) recorded in the same mice at the same time. This plateau was visible in two independent cohorts of mice (Extended Data Fig. 3a–d) and was not due to GCaMP sensor saturation in the VTA DA cell bodies because social stimuli were able to evoke substantially higher cell body activity in the same mice (Extended Data Fig. 3e–j).