RNA-triggered Cas12a3 cleaves tRNA tails to execute bacterial immunity

TL;DR

Cas12a3, a new type V CRISPR-Cas nuclease, targets and cleaves tRNA tails upon RNA recognition, inhibiting translation for bacterial immunity. This mechanism expands CRISPR applications, including diagnostics.

Key Takeaways

- •Cas12a3 is a novel CRISPR-Cas nuclease that cleaves tRNA tails after RNA target recognition, halting growth and providing anti-phage defense.

- •Unlike other Cas12 variants, Cas12a3 preferentially cleaves non-target RNA, specifically tRNA, without inducing DNA damage.

- •The nuclease uses a distinct tRNA-loading domain to position tRNA in its active site, enabling broad tRNA inactivation.

- •This discovery reveals tRNA targeting as a new adaptive immune strategy in bacteria, broadening CRISPR-based diagnostic tools.

Tags

Abstract

In all domains of life, tRNAs mediate the transfer of genetic information from mRNAs to proteins. As their depletion suppresses translation and, consequently, viral replication, tRNAs represent long-standing and increasingly recognized targets of innate immunity1,2,3,4,5. Here we report Cas12a3 effector nucleases from type V CRISPR–Cas adaptive immune systems in bacteria that preferentially cleave tRNAs after recognition of target RNA. Cas12a3 orthologues belong to one of two previously unreported nuclease clades that exhibit RNA-mediated cleavage of non-target RNA, and are distinct from all other known type V systems. Through cell-based and biochemical assays and direct RNA sequencing, we demonstrate that recognition of a complementary target RNA by the CRISPR RNA triggers Cas12a3 to cleave the conserved 5′-CCA-3′ tail of diverse tRNAs to drive growth arrest and anti-phage defence. Cryogenic electron microscopy structures further revealed a distinct tRNA-loading domain that positions the tRNA tail in the RuvC active site of the nuclease. By designing synthetic reporters that mimic the tRNA acceptor stem and tail, we expanded the capacity of current CRISPR-based diagnostics for multiplexed RNA detection. Overall, these findings reveal widespread tRNA inactivation as a previously unrecognized CRISPR-based immune strategy that broadens the application space of the existing CRISPR toolbox.

Similar content being viewed by others

Structural basis for the activation of a compact CRISPR-Cas13 nuclease

RNA-targeting CRISPR–Cas systems

RNA targeting unleashes indiscriminate nuclease activity of CRISPR–Cas12a2

Main

Immune defences across all domains of life counteract viral infections by clearing the invader or disabling host processes that are essential for viral replication. One growing theme associated with innate immune systems is the inactivation of tRNAs1,2,3,4,5. tRNAs have a critical role in translation, serving as the bridge between mRNAs and nascent proteins. Accordingly, inactivating a portion of the tRNA pool can impair the synthesis of viral proteins or drive systematic cellular shutdown to block viral replication1,2,4,6,7. Representative bacterial defences such as PrrC, VapC, colicin E5 and PARIS cleave the anticodon loop of specific tRNAs5,8,9,10,11. In animals, the type I interferons SLFN11 and SAMD9 cleave the acceptor stem and anticodon loop, respectively, of tRNAs to suppress codon-specific production of viral particles4,7,12,13.

Conspicuously absent from the set of immune defences that specifically use tRNA inactivation are CRISPR–Cas systems, the only known source of adaptive immunity in bacteria and archaea14. These widespread systems immunize against future infection by acquiring snippets of viral sequences expressed as CRISPR RNAs (crRNAs) that pair with CRISPR-associated (Cas) effector nucleases. The complex then searches for complementary target RNA or DNA that match the originating virus and, after target recognition, cleaves the bound nucleic acid targets to clear viral genomes or transcripts15,16,17. Some activated Cas nucleases also collaterally cleave non-target RNA or DNA with little sequence preference to halt cellular processes that are essential for viral replication and to drive growth arrest18,19,20,21. One such effector, the RNA-triggered Cas13 nuclease from Leptotrichia shahii (LshCas13a), was recently shown to cleave U-rich anticodon loops associated with a subset of tRNAs when activated in Escherichia coli22. However, LshCas13a also efficiently cleaves its target RNA at U-rich sequences to drive targeted silencing23,24,25,26. Thus, it remains unknown whether any CRISPR–Cas systems have evolved to preferentially cleave tRNAs over other RNA species, including their target RNA, as part of an immune response.

Here we report a previously uncharacterized clade of Cas nucleases, which we term Cas12a3. After target RNA recognition, these nucleases preferentially cleave the conserved 3′ CCA tails of tRNAs to drive growth arrest and block phage dissemination. Activated Cas12a3 engages the tRNA tail, acceptor stem and T-arm to load tRNA substrates into its RuvC nuclease domain for cleavage. Harnessing the distinct properties of Cas12a3, we expanded the multiplexing capacity of current CRISPR-based RNA detection approaches to illustrate one of the many applications of programmable RNA-mediated tRNA cleavage.

Cas12a3 and Cas12a4 halt growth without DNA damage

The phylogenetic proximity of the functionally diverse Cas12a nucleases (which target and cleave complementary DNA)17 and Cas12a2 nucleases (which target RNA and then indiscriminately shred RNA and DNA)27,28 indicated that other functionalities might exist in the adjacent phylogenetic space. To explore this possibility, we searched public databases for sequences closely related to Cas12a2. We identified 61 orthologues primarily from environmental metagenomic assemblies that resolved into two clades distinct from Cas12a2, Cas12a and each other (Fig. 1a,b, Extended Data Fig. 1 and Supplementary Data 1). Most of these were associated with CRISPR arrays and the spacer-acquisition genes cas1, cas2 and cas4 (Supplementary Table 1). We tentatively designate members of these clades Cas12a3 and Cas12a4, as further variants of Cas12a. These two clades retain the three motifs that form the canonical RuvC endonuclease domain and the domains and conserved residues involved in the processing of crRNA, the recognition of the protospacer-flanking sequence (PFS) and the zinc ribbon (ZR) (Fig. 1b). However, orthologues from the identified clades showed limited conservation of the aromatic clamp residues in Cas12a2, which are crucial for broad DNA collateral cleavage28, with Cas12a3 lacking these regions entirely (Fig. 1b and Extended Data Fig. 1).

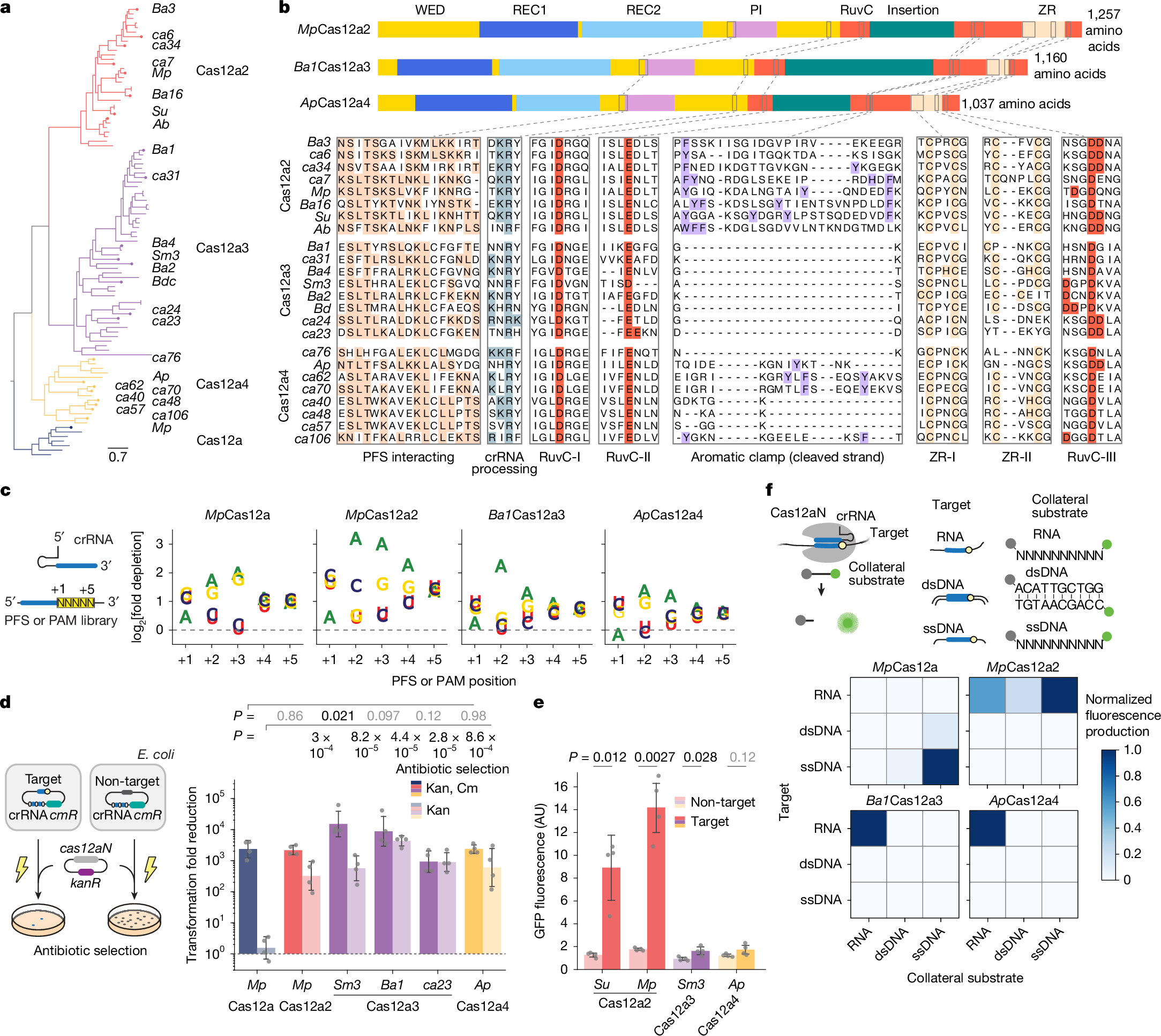

a, Phylogenetic analysis depicting Cas12a and the related Cas12a2, Cas12a3 and Cas12a4 clades. b, Domain and targeted sequence alignment across representative Cas12a2, Cas12a3 and Cas12a4 nucleases. c, Schematic (left) and quantification (right) of the nucleotide-depletion screen as part of the PFS (Cas12a2, Cas12a3 and Cas12a4) or protospacer-adjacent motif (PAM; Cas12a) determination for representative nucleases. Additional PFS screens are presented in Supplementary Fig. 2a. Results are the averages of independent experiments (n = 2). Note that the PAM for MpCas12a is the reverse complement of the sequence commonly reported for Cas12a nucleases (YYV). d, Schematic (left) and quantification (right) of the assessment of plasmid clearance versus growth arrest in E. coli based on variations of a plasmid interference assay. Plasmid clearance and growth arrest were differentiated on the basis of antibiotic selection for the target plasmid or the target plasmid and the nuclease plasmid. cmR, chloramphenicol-resistance cassette; kanR, kanamycin resistance cassette; Kan, kanamycin; Cm, chloramphenicol. e, Quantification of induction of the SOS DNA damage response in E. coli based on a transcriptional fluorescent reporter. Bars and error bars in d and e represent the geometric mean ± geometric s.d. and the mean ± s.d., respectively, of independent experiments starting from separate colonies (n = 4), with grey dots representing each measurement. f, Schematic (top) and measurement (bottom) of the assessment of different targets and cleavage substrates in vitro. Values represent the mean of independent experiments (n = 3 or 4). Complete time courses are shown in Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 2e. Statistical analyses were performed using two-tailed Welch’s t-tests with all biological replicates. P values that are not significant (P ≥ 0.05) are shown in grey. AU, arbitrary units. Illustrations of thunderbolts and Petri dishes in d reproduced from ref. 27, CC BY 4.0.

To investigate the possibility that Cas12a3 and Cas12a4 have distinct activities compared with Cas12a2, we first characterized representative Cas12a3 and Cas12a4 nucleases using our previously established plasmid interference assays in E. coli27. The nucleases were treated with a library of potential PFS sequences encoded in a target plasmid under antibiotic selection (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 2a). This assay identified a preference for a purine-rich PFS, a finding in line with the known preferences of Cas12a2 nucleases and the high amino-acid similarity in the PFS-interacting region across the orthologues (Fig. 1b). Using a consensus PFS, the Cas12a3 and Cas12a4 nucleases reduced the number of transformants even without antibiotic selection for the target plasmid, similar to a representative Cas12a2 from the microbial community of Microcerotermes parvus (MpCas12a2) (Fig. 1d). We obtained comparable results for different target sequences (Supplementary Fig. 2b) and observed impaired growth in liquid culture without antibiotic selection (Supplementary Fig. 2c). Cas12a2 and Cas12a3 nucleases further provided defence against T4 phage infection (Supplementary Fig. 2d). However, unlike Cas12a2, the Cas12a3 and Cas12a4 nucleases did not induce a measurable SOS DNA damage response, as indicated by a transcriptional reporter driven from the recA promoter27 (Fig. 1e). Thus, although Cas12a3 and Cas12a4 nucleases arrest growth after activation in a manner similar to Cas12a2, both nucleases induce a distinct mechanism of immunity.

Active Cas12a3 and Cas12a4 cleave RNA but not DNA

We next examined whether Cas12a3 and Cas12a4 orthologues accept DNA and RNA targets and cleavage substrates (Fig. 1f). Given that the Cas nucleases could have sequence preferences for specific substrates27,29,30, we used a randomized library of RNA and single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) substrates and a mixed-nucleotide sequence for the double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) substrate. As expected, MpCas12a (as a representative Cas12a nuclease) primarily cleaved the ssDNA substrate library and, to a limited extent, the dsDNA substrate in response to the ssDNA and dsDNA targets, respectively29,31. Moreover, MpCas12a2 cleaved all three substrates in response to the RNA target27,28 (Fig. 1f and Supplementary Fig. 2e). Similar to MpCas12a2, Cas12a3 from an unknown Bacteroidetes bacterium (Ba1Cas12a3) and Cas12a4 from a microbial community of the Alvinella pompejana hydrothermal vents worm (ApCas12a4) were also activated by the RNA target. However, they exclusively cleaved the RNA substrate library. When presented with additional individual ssRNA, ssDNA or dsDNA substrates in vitro, similar trends were observed for these nucleases and for Cas12a3 from Smithella sp. M82 (Sm3Cas12a3) (Extended Data Fig. 2). Notably, Ba1Cas12a3 and Sm3Cas12a3 only partially cleaved their target RNA even after prolonged incubation, which was in contrast to complete cleavage by ApCas12a4 and MpCas12a2. This result suggests that the RNA target is not the preferred cleavage substrate of Cas12a3. RNA-mediated RNA cleavage by Cas12a3 and Cas12a4 is consistent with the lack of a measurable SOS response in E. coli (Fig. 1d) and the absence of the aromatic clamp amino-acid residues in the nucleases of these clades (Fig. 1b and Extended Data Fig. 1). These observations reveal that exclusive RNA-activated RNA cleavage also occurs in the highly diverse family of Cas12 nucleases32, similar to the cleavage activities of the phylogenetically distinct Cas13 nucleases33.

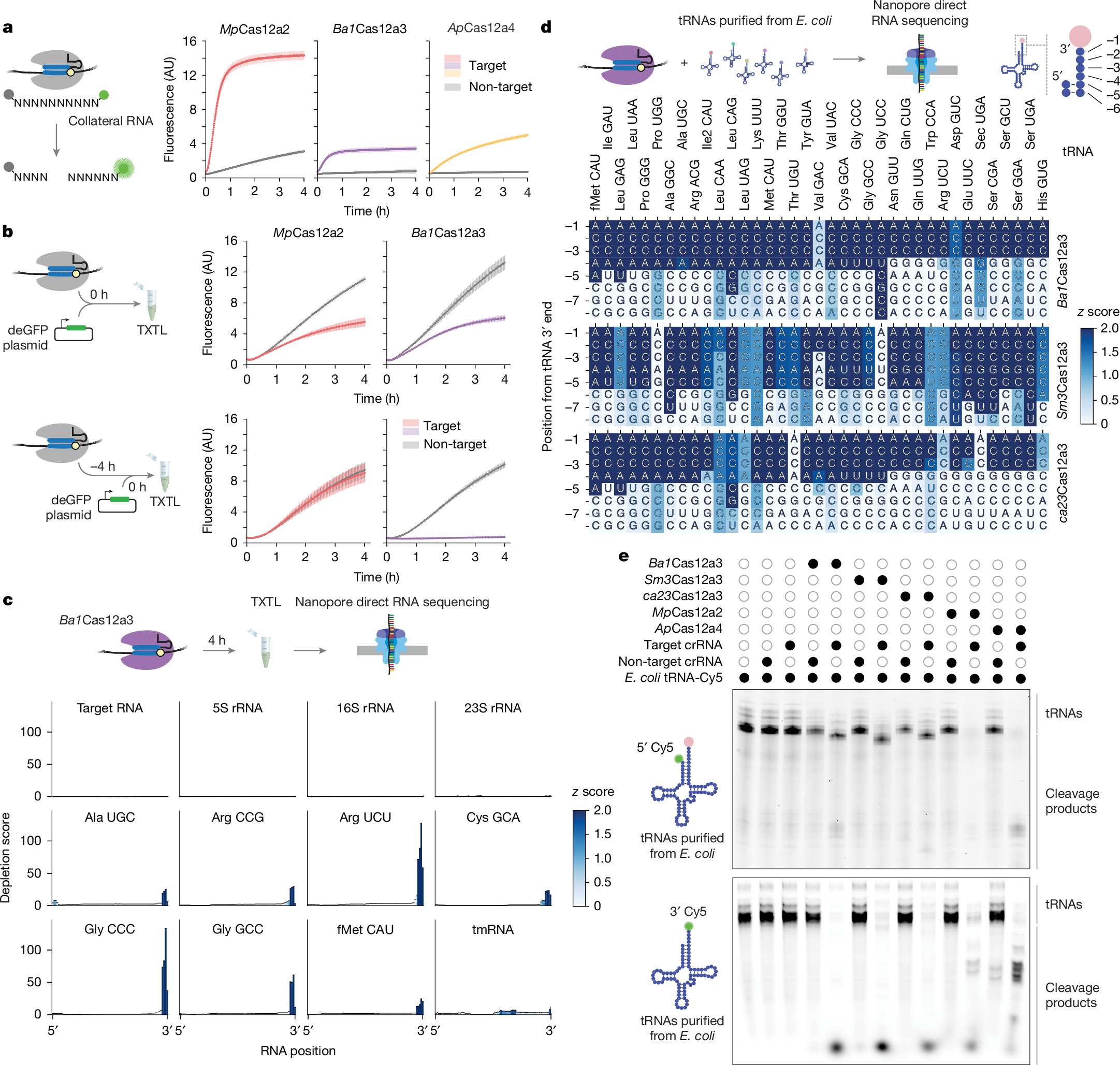

Cas12a3 prefers specific RNA substrates

Building on the limited cleavage of target RNA by these nucleases, we noted that Ba1Cas12a3 also exhibited 3.8-fold less cleavage of the RNA substrate library compared with MpCas12a2 (Fig. 2a). By contrast, ApCas12a4 exhibited a continual increase in fluorescence over the course of the reaction without plateauing and efficiently cleaved its target RNA in vitro (Extended Data Fig. 2). We speculated that reduced cleavage of the RNA library by Ba1Cas12a3 resulted from a selective preference for specific RNA substrates.

a, Schematic (left) and quantification (right) of the time course of cleavage of the RNA substrate library from Fig. 1f. Dots and bars represent the mean ± s.d. from independently mixed in vitro reactions (n = 4). AU, arbitrary units. b, Schematic (left) and quantification (right) of the fluorescence time courses of TXTL assays assessing nuclease activity based on silencing of deGFP expression. Dots and bars represent the mean and s.d. from independently mixed TXTL reactions (n = 3 or 4). c, Schematic (top) and quantification (bottom) of RNA sequencing of total RNA ≤ 200 nucleotides by Nanopore from TXTL reactions with Ba1Cas12a3 and a target or non-target RNA after 4 h. Values represent independent TXTL reactions (n = 3). The colour map indicates the z score of depletion scores at each position. d, Schematic (top) and quantification (bottom) of Nanopore sequencing of purified E. coli MRE600 tRNAs incubated with Ba1Cas12a3, Sm3Cas12a3 or ca23Cas12a3 under targeting versus non-targeting conditions. Values represent independent reactions (n = 3), with depletion z scores for each nucleotide as a colour map. Shown tRNAs (labelled with the corresponding anticodons) were detected in every nuclease reaction across the three independent experiments. Apparent cleavage sites ending in A could be shorter by one or (in the case of tRNAfMet(CAU)) two nucleotides towards the 3′ end owing to the use of a poly(A) extension to the cleavage product. See Supplementary Figs. 3 and 5 for full tRNA sequences with single-nucleotide depletion scores. e, Cleavage patterns of E. coli MRE600 tRNAs incubated with activated nucleases. The tRNA pool was 5′ labelled with a fluorophore, leaving the amino acyl group attached (top), or by replacing the 3′ amino acyl group with a fluorophore (bottom). Gel images are representative of independent cleavage reactions (n = 3). Open and closed circles represent the absence or presence, respect