Surface optimization governs the local design of physical networks

TL;DR

Physical networks like brain connectomes and vascular systems violate traditional wiring minimization predictions. Surface optimization, accounting for 3D geometry, explains trifurcations and branching angles, aligning with empirical data across diverse networks.

Key Takeaways

- •Physical networks show systematic deviations from Steiner graph predictions, including trifurcations and non-symmetric branching angles.

- •Surface minimization, considering full 3D geometry, maps to string theory tools and better predicts local network morphology.

- •Empirical data from neurons, vasculature, and plants support surface optimization over length or volume minimization.

- •Stable orthogonal sprouts, predicted by surface minimization, enhance functionality in real networks like synapse formation.

- •The study highlights the importance of material constraints in network design, moving beyond simplified wiring models.

Tags

Abstract

The brain’s connectome1,2,3 and the vascular system4 are examples of physical networks whose tangible nature influences their structure, layout and, ultimately, their function. The material resources required to build and maintain these networks have inspired decades of research into wiring economy, offering testable predictions about their expected architecture and organization. Here we empirically explore the local branching geometry of a wide range of physical networks, uncovering systematic violations of the long-standing predictions of wiring minimization. This leads to the hypothesis that predicting the true material cost of physical networks requires us to account for their full three-dimensional geometry, resulting in a largely intractable optimization problem. We discover, however, an exact mapping of surface minimization onto high-dimensional Feynman diagrams in string theory5,6,7, predicting that, with increasing link thickness, a locally tree-like network undergoes a transition into configurations that can no longer be explained by length minimization. Specifically, surface minimization predicts the emergence of trifurcations and branching angles in excellent agreement with the local tree organization of physical networks across a wide range of application domains. Finally, we predict the existence of stable orthogonal sprouts, which are not only prevalent in real networks but also play a key functional role, improving synapse formation in the brain and nutrient access in plants and fungi.

Similar content being viewed by others

Prediction of neural activity in connectome-constrained recurrent networks

The small world coefficient 4.8 ± 1 optimizes information processing in 2D neuronal networks

Structure-function clustering in weighted brain networks

Main

The vascular system and the brain are examples of physical networks that differ from the networks typically studied in network science owing to the tangible nature of their nodes and links, which are made of material resources and constrain their layout. The importance of these material factors has been noted in many disciplines: as early as 1899, Ramón y Cajal suggested that we must consider the laws conserving the ‘wire’ volume to explain neuronal design8 and in 1926, Cecil D. Murray applied volume minimization principles to vascular networks, deriving the branching principles known as Murray’s law9. Today, wiring optimization is used to account for the morphology and the layout of a wide range of physical systems10,11, from the distributions of neuronal branch sizes12 and lengths13 to the morphology of plants14, the structure15 and flow16 in transport networks, the layout of supply networks17, the wiring of the Internet18 or the shape of inter-nest trails built by Argentine ants19 and the design of 3D-printed tissues with functional vasculature20.

The premise of wiring economy approaches is the optimal wiring hypothesis, which conceptualizes physical networks as a set of connected one-dimensional wires whose total length is minimized21,22,23. The optimal wiring in this case is exactly predicted by the Steiner graph24,25,26,27. However, the lack of high-quality data on physical networks has limited the systematic testing of the Steiner predictions to single neuron branches28 and ant tunnels19 and offered at best mixed evidence of their validity28,29. Yet, data availability has substantially improved in the past few years, thanks to advances in microscopy and three-dimensional reconstruction techniques, offering access to the detailed three-dimensional structure of physical networks ranging from high-resolution layouts of brain connectomes1,2,3 to vascular networks4 or the structure of coral trees30. Here we take advantage of these experimental advances to explore in a quantitative manner the role of wiring optimization in shaping the local morphology of physical networks. We begin by documenting systematic deviations from both the Steiner predictions24 and volume optimization9,28,29, failures that we show to be rooted in the hypothesis that approximates the cost of physical networks as the sum of their link lengths21,22,23 or as simple cylinders28,29. Indeed, the links of real physical networks are inherently three-dimensional, prompting us to suggest that their true material cost must also consider surface constraints. Building on previous analyses that introduced volumetric constraints9,28,29, here we successfully account for the local surface morphology, ensuring that, when links intersect, they morph together continuously and smoothly, free of singularities, as dictated by the physicality of their material structure. To achieve this, we map the local tree structure of physical networks into two-dimensional manifolds, arriving at a numerically intractable surface and volume minimization problem. We discover, however, a formal mapping between surface minimization and high-dimensional Feynman diagrams, which allows us to take advantage of a well-developed string-theoretical toolset5,6,7 to predict the basic characteristics of minimal surfaces. We find that surface minimization can not only account for the empirically observed discrepancies from the Steiner predictions but offers testable predictions on the degree distribution and the angle asymmetry of physical networks, which we can falsify, offering a crucial window into the design principles of physical networks.

Steiner graphs

The Steiner graph problem24 begins with M spatially distributed nodes (Fig. 1a), with the task of connecting these nodes through the shortest possible links. The key insight of the Steiner solution is that, by adding intermediate nodes to serve as branching points (Fig. 1b), the obtained link length can be shorter than any attempt to connect the nodes directly24 (Fig. 1a). Although for arbitrary M the Steiner problem is NP-hard, for M = 4, we can get an exact solution, resulting in a globally optimal Steiner graph that is characterized by three strict local rules (Fig. 1b). (1) Bifurcation only. All branching instances represent bifurcations, in which a single link splits into two daughter links. Consequently, all intermediate nodes have degree k = 3 and higher-degree nodes (k > 3) are forbidden. (2) Planarity. At a bifurcation, all three links are embedded in the same plane (Ω = 2π). (3) Angle symmetry. All three branches of a bifurcation form the same angle θ = 2π/3 with each other.

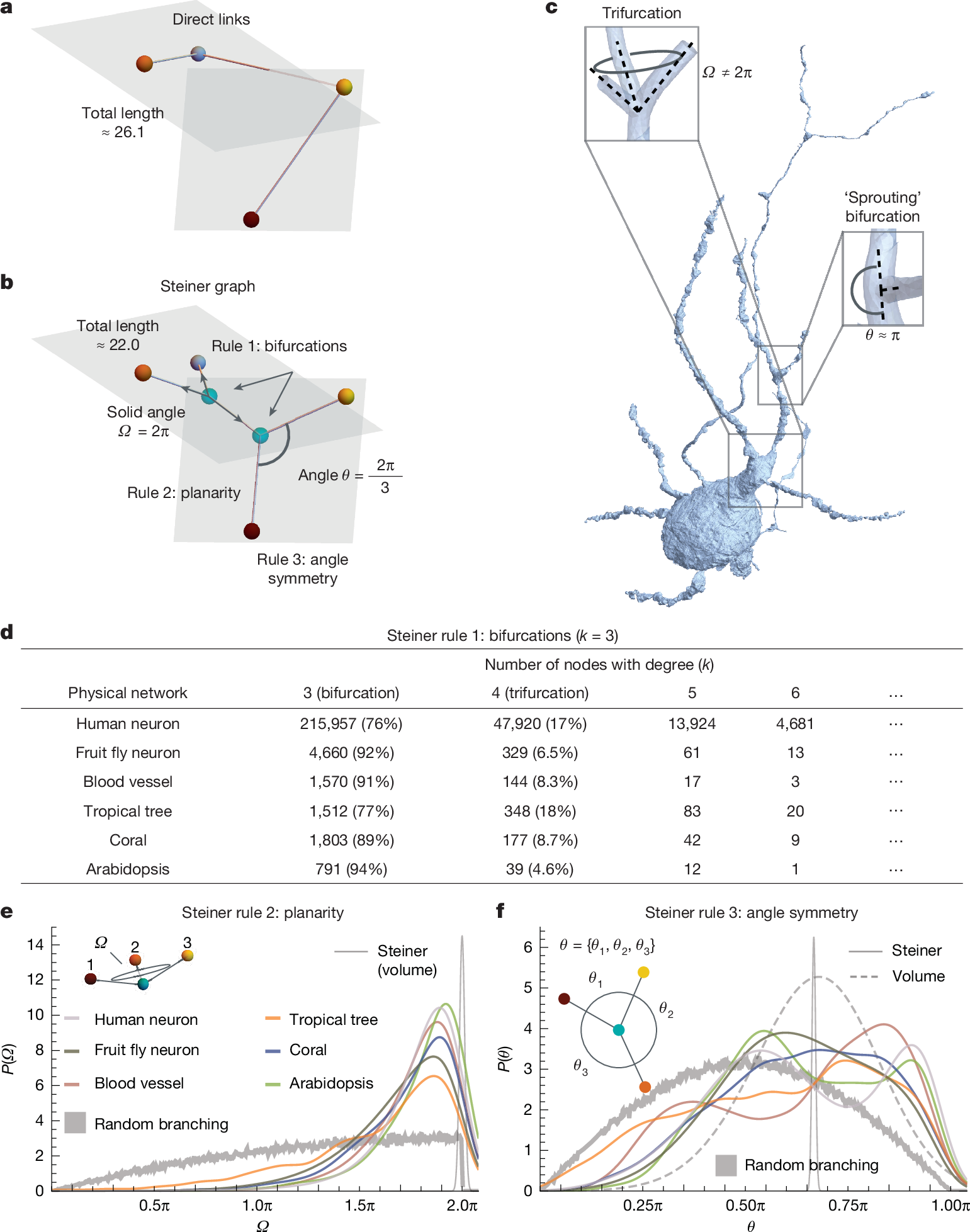

a, Physical networks aim to connect spatially distributed nodes (coloured) with physical links in three dimensions. If we connect nodes directly, the wiring cost (total link length) is about 26.1. b, The Steiner graph minimizes the wire length by permitting intermediate nodes (green), resulting in the total wire length of approximately 22.0. The Steiner graph offers three predictions. Rule 1: all branching instances are bifurcations with degree k = 3. Rule 2: bifurcations are all planar, having a solid angle of Ω = 2π. Rule 3: the angles between adjacent links are θ = 2π/3. Volume optimization, which generalizes links as simple cylinders of varying thickness, preserves rules 1 and 2 and predicts a broader distribution for θ, peaked around 2π/3. c, A neuron of the human connectome, demonstrating the violations of the Steiner rules. In the top inset, we highlight a trifurcation (k = 4) violating rule 1. We also highlight a non-symmetric branching angle, in which links sprout out perpendicularly (right inset), breaking rule 3. d, The percentage of k = 4 nodes across our six empirical locally tree-like physical networks. We observe roughly 15% of the nodes violating Steiner rule 1. e, The probability density P(Ω) versus Ω as obtained from all bifurcations (k = 3) in our empirical network ensemble (coloured solid lines). The observed density functions are more prone to Steiner rule 2 (thin grey line) than to random branching without optimization (thick grey line). f, The probability density P(θ) versus θ as obtained from all bifurcations (coloured solid lines). Once again, we observe a clear discrepancy from Steiner (thin grey line) and a tendency towards random branching (thick grey line) or volume optimization of cylindrical links with random thickness (dashed grey line).

To test the validity of the local predictions of the Steiner solution, we collected three-dimensional resolved data of six classes of physical networks (Supplementary information Section 1): (1) human neurons1 (also in Fig. 1c); (2) fruit fly neurons31; (3) human vasculature4; (4) tropical trees from moist forests32; (5) corals of several species30; (6) arabidopsis at different growth stages33. As wiring optimization relies on the skeleton representations of physical networks, we confirmed that our test of Steiner’s prediction is not sensitive to the choice of the particular skeletonization algorithm (Supplementary information Section 1). To examine the validity of rule 1 (bifurcation only), we extracted the degree distribution of each skeletonized network. In agreement with the Steiner principle (an outcome also predicted by volume optimization of simple cylinders28,29), we observe a prevalence of k = 3 nodes, accounting, for example, for 79% of the nodes in the human neurons and for 94% in arabidopsis. Yet, we also observe a substantial number of trifurcations (k = 4) and several even higher degree (k = 5, 6) nodes (Fig. 1d), violating the Steiner and volume optimization prediction34,35. Note that, because of errors in skeletonizing a physical motif, two closely spaced bifurcations may be mistakenly identified as a trifurcation or, conversely, a trifurcation may be incorrectly perceived as two bifurcations36. We therefore verified that the observed high-degree nodes (as demonstrated in Fig. 1c) cannot be attributed to resolution limits (Supplementary information Section 1).

To examine the validity of rule 2 (planarity), which is predicted by both Steiner and volume optimization, we quantified the planarity for each bifurcation (k = 3) by measuring the probability P(Ω) that the three links span a solid angle Ω. We find that, in all of the studied networks, P(Ω) is strongly peaked at a solid angle that is smaller than the expected Ω = 2π, which is necessary (and sufficient) for planarity (Fig. 1e). Finally, to test the validity of rule 3 (angle symmetry), we extracted the pairwise angles (θ1, θ2, θ3) between the links at each bifurcation, measuring the probability density P(θ). As Fig. 1f indicates, none of the six classes of real networks have a peak at the predicted θ = 2π/3 but instead the branching angles are broadly distributed, an asymmetry violating the Steiner prediction. Note that P(θ) predicted by volume optimization is also peaked around θ = 2π/3 but it can account for a broader range of branching angles thanks to the fact that links can have varying thickness28,29.

Taken together, although we see the signature of the Steiner theorem and volume optimization in the prevalence of k = 3 nodes, the optimal wiring hypothesis is unable to account for the existence of k > 3 nodes, the prevalence of non-planar bifurcations and the lack of θ = 2π/3 symmetry, results that question the validity of the optimal wiring hypothesis for physical networks.

Beyond wires—physical networks as manifolds

The Steiner problem relies on the hypothesis that nature aims to minimize the total length of the links, solving an inherently global problem. However, real physical networks have rich local geometries (Fig. 1c), characterized by varying diameters9 and non-cylindrical surface morphologies. Over the past century, beginning with Murray’s 1926 work, researchers have combined geometry-based volume optimization calculations9,28,29 with algorithmic approximations to identify network configurations that satisfy the inherent system-specific constraints and align with experimental data in specific domains37,38,