Direct observation of the Migdal effect induced by neutron bombardment

TL;DR

Researchers have directly observed the Migdal effect in neutron-nucleus collisions with 5σ significance, confirming a long-predicted phenomenon. This provides experimental validation crucial for enhancing sensitivity in light dark matter detection experiments.

Key Takeaways

- •First direct observation of the Migdal effect in neutron-nucleus scattering, achieving 5σ statistical significance with 6 candidate events.

- •Measured Migdal cross-section to nuclear recoil cross-section ratio of 4.9_{-1.9}^{+2.6} × 10^{-5}, consistent with theoretical predictions.

- •Uses a specialized gaseous pixel detector to image nuclear recoil and Migdal electron tracks, reducing background noise effectively.

- •Validates the Migdal effect's role in enhancing detector sensitivity for light dark matter searches, addressing a key experimental gap.

- •Findings support theoretical models and pave the way for improved strategies in detecting sub-GeV dark matter particles.

Tags

Abstract

The search for dark matter focuses now on hypothetical light particles with masses ranging from MeV to GeV (refs. 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12). These particles would leave very faint signals experimentally. A potential avenue for enhancing experimental sensitivity to light matter relies on the Migdal effect13,14,15, which involves the detectable ejection of electrons following the instantaneous accelerations of atoms colliding with neutral dark matter. However, although the Migdal effect could be equally generated in controlled experiments with neutral projectiles, a direct experimental observation of this effect is missing, casting doubt on the reliability of detection experiments relying on this effect. Here we report the direct observation of the Migdal effect in neutron–nucleus collisions, achieving a statistical significance of 5 standard deviations, which rests on 6 candidate events selected out of almost 106 recorded events. Our experiments have determined the ratio of the Migdal cross-section to the nuclear recoil cross-section to be \({4.9}_{-1.9}^{+2.6}\times {10}^{-5}\), in which nuclear recoils exceed 35 keVee and electron recoils span 5–10 keV. These findings are consistent with theoretical predictions. This work resolves a long-standing gap in experimental validation, which not only strengthens the theoretical foundation of the Migdal effect but also paves the way for its application in light dark matter detection.

Main

Dark matter, an invisible yet gravitationally interacting component of the Universe16,17,18, remains one of the most profound unsolved mysteries in modern physics. Although experiments focusing on weakly interacting massive particles have successfully approached the neutrino fog1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10, conclusive evidence for dark matter has yet to be found. The dark matter is broadening its focus. A global experimental effort is now probing models in which the dark matter particle has a mass roughly between MeV and GeV. Within this range, theoretical insights strongly support the plausibility of dark matter potentially existing in the mass range from MeV to GeV with a successful thermal production mechanism11,12. The faint signals associated with light dark matter necessitate substantial reductions in the detection thresholds of existing detectors. Despite the achievement of detection thresholds around 100 eV in tonne-scale experiments, the abilities remain inadequate now for detecting light dark matter.

A promising new strategy to tackle this challenge is the Migdal effect. It describes a process in which energy transfers from an atomic nucleus to a surrounding electron13,14,15. When a neutral particle, such as dark matter or a neutron, interacts with an atomic nucleus, it causes the nucleus to recoil. Along with this recoil, an additional electronic recoil is produced because of the excitation of atomic electrons. This additional component can generate a signal in the detectors that is above the energy threshold. Theoretical discussions of this effect in the context of dark matter direct detection date back to the mid-2000s (refs. 19,20,21), and it was also considered in the interpretation of the DAMA experimental data22. A reformulation of Migdal’s original approach has been done in ref. 23. Further dedicated investigation has since revealed its relevance for direct detection searches24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31. To date, measurements of the Migdal effect have been limited to nuclear decay processes involving α-decay32,33,34,35 or β-decay36,37,38,39,40. Its role in nuclear scattering, particularly when an electrically neutral projectile interacts with the nucleus, remains unverified. This has motivated recent experimental efforts to observe the Migdal effect in nuclear scattering experiments41,42,43. However, no observational results have been reported so far, to our knowledge. Despite this gap, several direct experiments have leveraged the Migdal effect to search for sub-GeV dark matter44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51, extending the reach of light dark matter direct detection. The lack of direct observation undermines the conclusions drawn from dark matter experiments that rely on the existence of the Migdal effect.

To address this issue, we develop a specialized gaseous pixel detector designed for high-precision imaging of nuclear recoil (NR) and Migdal electron tracks. This detector features a broad energy detection range, excellent vertex resolution ability, low noise levels and advanced imaging abilities. These design features allow us to identify NRs and Migdal electrons with a marked reduction in background noise. In this study, we report the direct observation of the Migdal effect. In the experiment, we identify six signal candidates, exceeding the rate of background reactions by 5 standard deviations. The measurements indicate a Migdal effect cross-section relative to the NR cross-section ratio of \({\text{(}4.9}_{-1.9}^{\text{+}2.6})\times {10}^{-5}\). Our findings provide robust evidence for enhancing detector sensitivity in direct light dark matter experiments using the Migdal effect.

Experiment

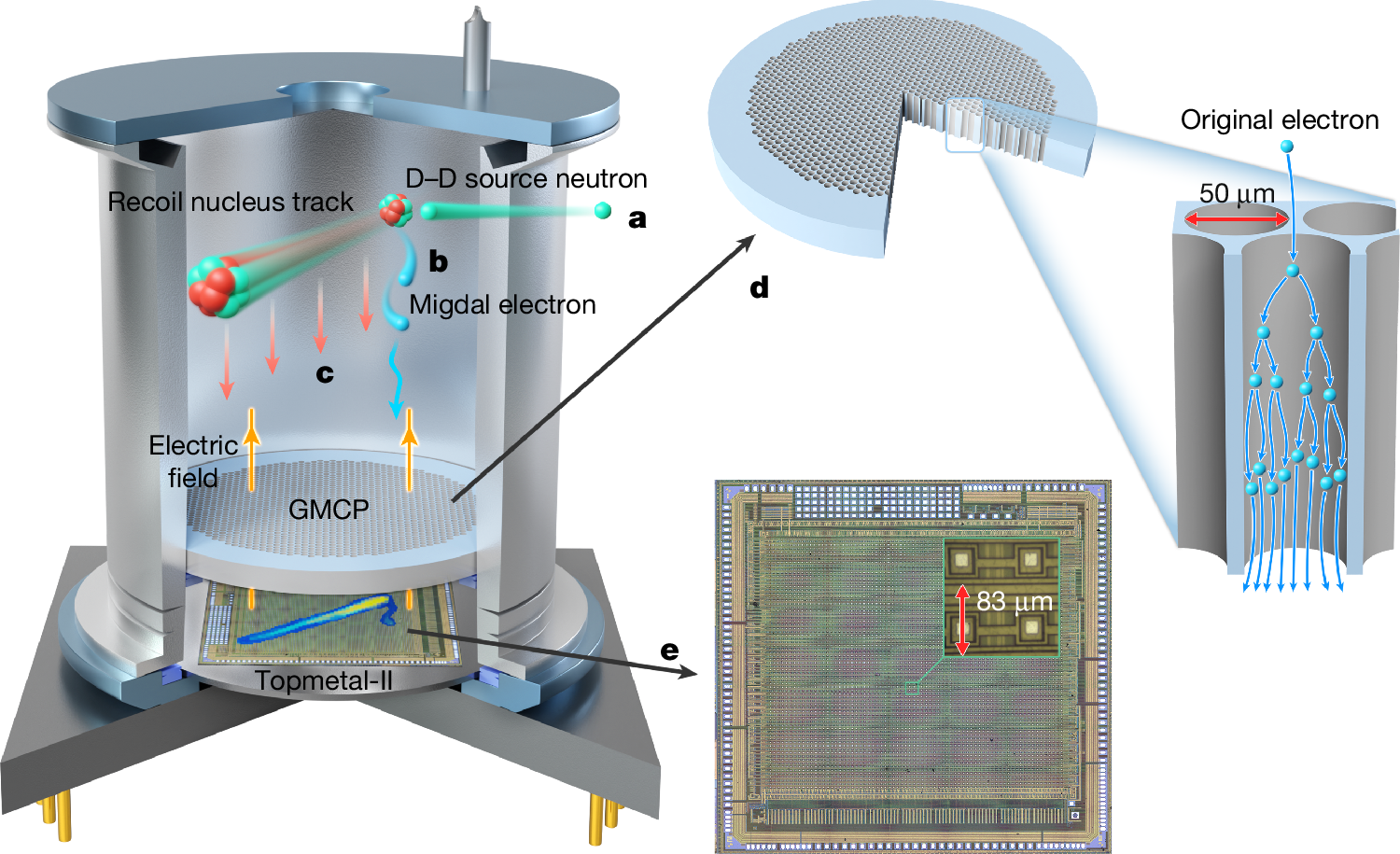

Confirming the Migdal effect requires the simultaneous observation of both the recoil nucleus and the Migdal electron, with the two tracks forming a topological structure with a common vertex. This places stringent requirements on the imaging ability and position resolution of the detector. In our experiment, we use a mixture of 40% helium and 60% dimethyl ether (DME, CH3OCH3) as the track imaging medium to ensure the formation of clear and sufficiently long electron tracks. We use a charge-sensitive pixel array chip52 with a pixel size of 83 μm for track imaging and an equivalent noise charge of 13.9 e−. The working principle of the detector is shown in Fig. 1.

The detector consists of a beryllium window at the top, a ceramic tube, a gas microchannel plate (GMCP) in the middle and a Topmetal chip at the bottom, with an electric field applied within the detector to guide electron drift. a, The neutron beam passes through the effective area of the detector. b, Neutrons scatter with gas molecules in the detector, generating recoiling nucleons. While in the recoil process, atoms emit Migdal electrons. c, Charged particles interact with the gas in the drift region, causing ionization of gas atoms. The resulting electrons are drifted by the electric field towards the GMCP. d, Electrons enter the pores of the GMCP and undergo ionization multiplication in a strong electric field, amplifying the signal. e, The Topmetal-II induces charge signals, in which the distribution and quantity of these ionized electrons reflect the track and energy deposited by the charged particles.

To obtain the recoil nucleus signal, we use a compact D–D neutron generator53 to produce 2.5 MeV neutrons that bombard the mixed gas in the detector. Simultaneously, to shield against background radiation such as gamma rays from the neutron source, the detector is positioned 40 cm away from the D–D neutron source and surrounded by 1 cm lead shield to mitigate environmental gamma radiation. Moreover, liquid scintillation detectors are used during the experiment to monitor neutron flux intensity and the neutron energy spectrum.

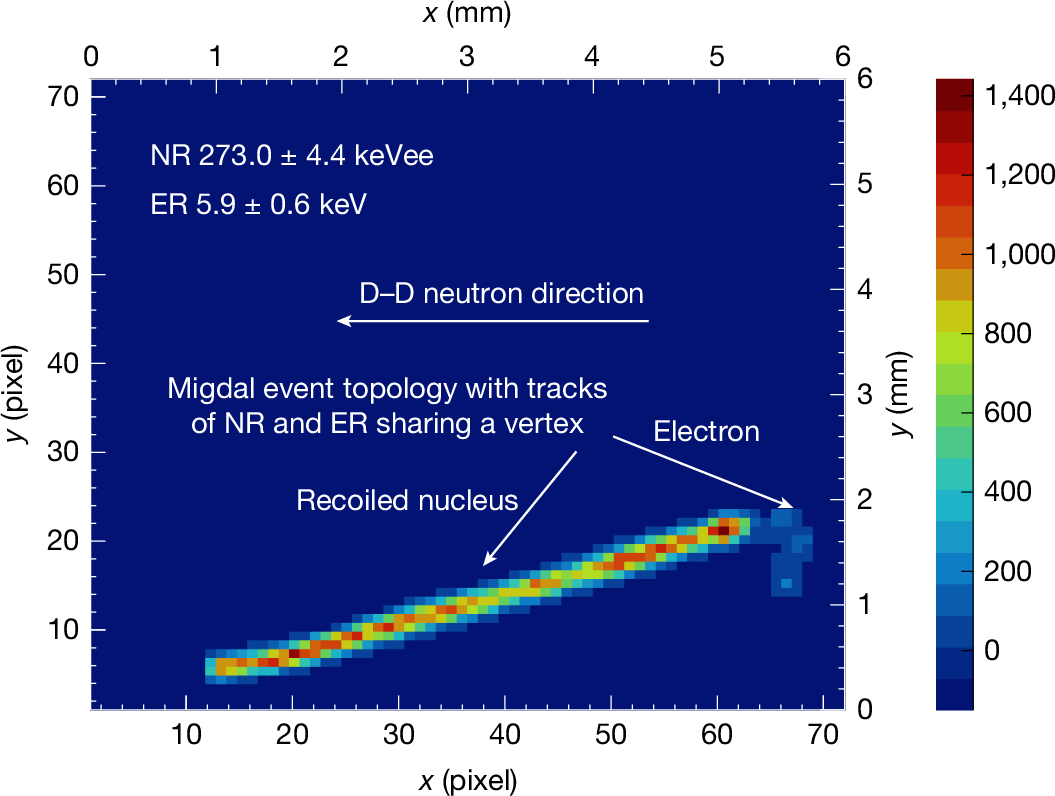

During the experiment, the detector triggers and saves the tracks, energy and time information of recoil nucleus events by comparing the number of over-threshold pixels before and after the signal arrival. To effectively distinguish tracks, the cluster segmentation algorithm54 is applied to separate spatially unrelated tracks in each frame. Tracks with deposition energy exceeding 35 kiloelectron volts (keVee) and vertices within the effective volume of the detector are chosen. The discrimination between NRs and electron recoils (ERs) is based on their energy deposition density dE/dX (ref. 55) and circularity56. Here, dE/dX is defined as the ratio of the energy deposited by the track to the two-dimensional (2D) projected length of the track. Circularity is a geometric feature metric used to quantify the deviation of a planar shape from a perfect circle, with its value range being (0, 1]. A value closer to 1 indicates that the shape more closely approximates an ideal circle. Under the same dE/dX conditions, recoil nucleus tracks with energy deposition exceeding 35 keVee are typically longer and geometrically straighter than electron tracks. Therefore, the 2D distribution of circularity and dE/dX can be effectively used to distinguish between ERs and NRs. The selection criteria for Migdal events are detailed in the Methods. To exclude low-energy background electrons, the energy deposition of electron tracks must fall within the range of 5–10 keV.

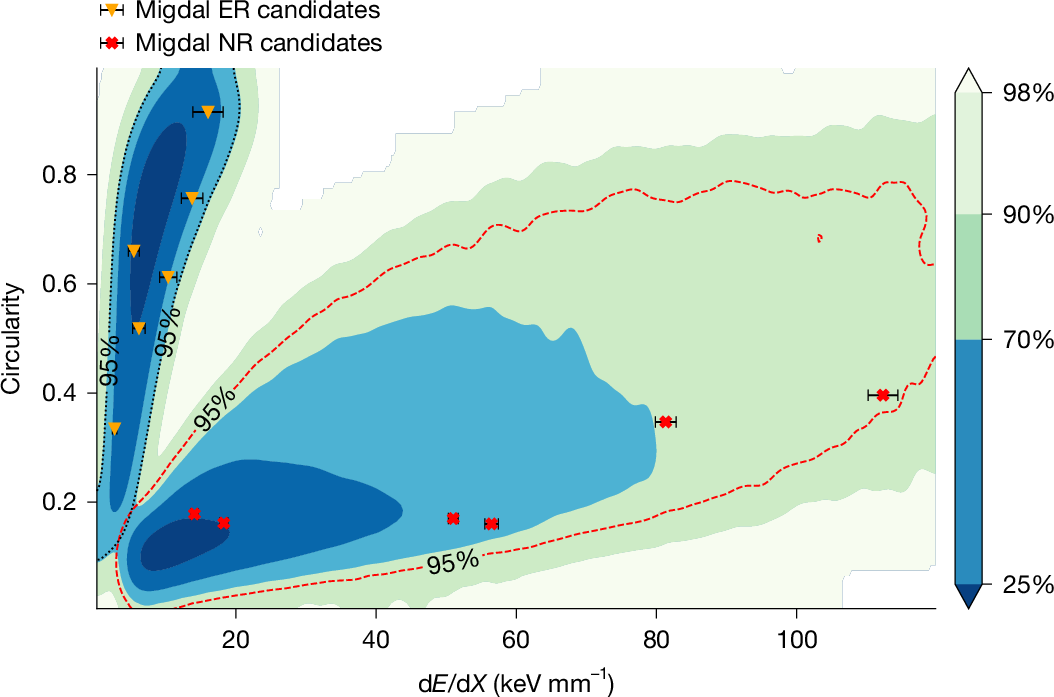

In the experiment, we collect data for approximately 150 h, and a total of 8.17 × 105 events are recorded. We identify six recoil nucleus–electron common vertex events that meet the event selection criteria, with an example shown in Fig. 2. In Fig. 3, the simulated distributions of electrons and experimental distribution of recoil nuclei are presented. The ERs and NRs are separated into two clearly distinguishable regions. The measured ER and NR of six Migdal events are superimposed.

The cluster on the left represents the characteristic distribution of simulated 4–10 keV electrons, with the electron energy spectrum derived from the theoretically calculated Migdal electron energy spectrum. The differently coloured contour lines indicate the proportion of events enclosed within their respective regions relative to the total number of events. The cluster at the bottom right shows the NR events from experimental data. The black dashed contour outlines the 95% distribution region for electrons, and the red dashed contour outlines the 95% distribution region for recoiled nuclei. The measured ER and NR of six Migdal events are superimposed.

Background

The search for Migdal events primarily relies on the topological features of the tracks: NRs share a vertex with ERs and are produced almost simultaneously. By exploiting this characteristic, the rate of background events can be significantly reduced. We have combined experimental data with Monte Carlo simulations to estimate the expected values and associated errors for each background component, normalized to the number of recoil nuclei. Background can be divided into two categories: beam-related and beam-unrelated. In our experiment, the total background value is 0.229 ± 0.032 (stat) ± 0.043 (sys). The largest contribution comes from the background produced by the chance coincidence of NR tracks with photoelectrons and Compton electrons associated with the neutron beam. The second significant contribution is from the δ-rays produced by recoil nuclei. Other beam-related backgrounds are all less than 10−3. Significant contributions from beam-unrelated backgrounds include cosmic δ-rays and trace contaminants decay background. Details of the backgrounds are discussed in the Methods.

Ratio of Migdal cross-section to NR cross-section

The observed signals have a statistical significance exceeding 5 standard deviations, strongly suggesting that the observed event topology is due to the Migdal effect. Based on the observed events, the ratio of the Migdal cross-section to the NR cross-section is estimated as follows:

where \({n}_{\text{obs}}^{\text{ER}}\), \({n}_{\text{obs}}^{\text{bg}}\) and \({n}_{\text{tot}}^{\text{NR}}\) are the observed numbers of Migdal events, expected background counts and total NR, respectively; εacc, εER and εNR are the acceptance rate of the events and reconstruction selection efficiency for ER and NR, respectively. The parameters and uncertainties used in the calculation are summarized in Table 1. The resulting ratio of the Migdal cross-section to the NR cross-section is \({\text{(}4.9}_{-1.9}^{+2.6})\times {10}^{-5}\).

Conclusion

In this study, we present the direct evidence of the Migdal effect in neutron–nucleus scattering—a phenomenon predicted more than 80 years ago but confirmed only now with a statistical significance exceeding 5σ. This result establishes a crucial benchmark for nuclear and particle physics, providing an experimental foundation for future theoretical and experimental investigations. By validating the Migdal effect, we address a long-standing gap in the scientific understanding of fundamental interactions and offer a potential approach for the detection of light dark matter. Notably, our measured relative Migdal cross-section of \({\text{(}4.9}_{-1.9}^{+2.6})\times {10}^{-5}\) is in good agreement with the theoretical prediction of 3.9 × 10−5 within the experimental uncertainties (see Methods, ‘Theory’).

The implications of this discovery are profound, particularly in the search for light dark matter. For decades, the Migdal effect has been an unverified assumption in neutral scattering that is regarded as an effective process for enhancing the ability to detect dark matter. Our findings provide a basis for re-evaluating these scenarios, and future work can build on these results to refine detection strategies and potentially enhance the sensitivity of dark matter searches.