Environmentally driven immune imprinting protects against allergy

TL;DR

Exposure to diverse environmental antigens in early life generates cross-reactive immune memory, protecting against allergic sensitization by promoting IgG-dominant responses over IgE. This environmentally driven immune imprinting occurs during a perinatal window and can suppress established allergies.

Key Takeaways

- •Pet shop mice exposed to diverse environments develop cross-reactive immune memory, leading to protection from allergic sensitization and anaphylaxis.

- •Protection correlates with IgG-dominant humoral responses to allergens, driven by pre-existing memory T cells producing IFNγ.

- •Environmental effects on allergy protection occur during a perinatal window, as fostering pet shop mice onto SPF conditions restores susceptibility.

- •Cross-reactive immunity can prevent allergy even with low protein sequence similarity, highlighting a mechanistic link between environment and immune function.

Tags

Abstract

Allergic diseases are caused by overexuberant type II immune responses mounted against environmental antigens1. The allergic state is typified by the presence of allergen-reactive immunoglobulin E (IgE), which triggers mast cell degranulation upon allergen encounter, manifesting in pruritis, oedema and, in severe cases, anaphylaxis. Over the past century, the prevalence of allergic diseases has increased markedly, suggesting that environmental rather than genetic factors are mediating this change2. Although many hypotheses connecting environment to allergy exist3,4,5,6, the biological mechanisms that underpin environmentally mediated protection from allergy are unknown. Here we show, using a mouse model of allergic disease, that exposure to immunostimulatory environments generated cross-reactive adaptive immune memory, which tracked with obstructed type II immune responses upon allergen exposure. We found that engagement of cross-reactive adaptive immunity protected against future allergic sensitization and suppressed established allergic responses. Cross-reactivity in a tolerogenic context also prevented allergy, with the effect extending across antigenically complex exposures even at low protein sequence similarity. Our findings demonstrate a mechanistic relationship between environment and allergy, with general implications for adaptive immune function in natural settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Type 2 immunity in allergic diseases

Epithelial cell membrane perforation induces allergic airway inflammation

Pathogenesis of allergic diseases and implications for therapeutic interventions

Main

The adaptive immune system couples antigen recognition with distinct effector functions for efficient control of diverse foreign agents. Viral and bacterial infections induce effector functions that are collectively referred to as type I immune responses, whereas type II immune responses are typically elicited through exposure to parasites, irritants and toxins7. Allergic diseases, including asthma, atopic dermatitis and food allergy, are considered to be exaggerated type II immune responses mounted against otherwise innocuous or mild insults. Although underlying genetic factors determine individual predisposition towards allergy development, epidemiological evidence suggests that environmental changes are driving the recent rise in allergic diseases3,8,9. The evidence for environmental influence on allergy in humans may be summarized in three observations: (1) that the prevalence of allergic disease has a nonuniform distribution across the world; (2) that individuals from similar genetic backgrounds have different rates of allergy regionally; and (3) that the incidence of allergies has increased rapidly over the past century, at a pace that cannot be explained by genetics alone2,10,11,12,13,14.

Most, but not all, cases of allergic disease initiate during infancy or childhood, and the allergic state persists for an extended period, often the entire lifespan of the individual15. Therapeutic interventions may provide desensitization towards specific allergens, but do not durably alter the underlying allergic immune setpoint, suggesting that allergic or non-allergic immune states are established upon initial allergen encounters and are maintained thereafter16,17. Thus, environmental effects that influence polarization towards either opposing allergic or non-allergic states are likely to occur before or during primary exposure to a novel allergen. The present study was undertaken to identify, in a mouse model of allergic sensitization, environmental factors relevant to protection from allergic disease.

Pet shop mice are protected from allergy

Previous studies have shown that the immune systems of mice raised in specific pathogen-free (SPF) conditions are similar to those of neonatal humans, whereas the immunological profiles of mice raised outside laboratory settings or collected from the wild resemble those of healthy adult humans18,19. Because adult humans, unlike infants or SPF mice, are generally protected from allergic sensitization, we explored whether non-SPF mice would also be protected from developing allergies. Outbred non-SPF mice were procured from a local breeder (hereafter referred to as pet shop mice). Pet shop mice were subjected to pathogen testing and faecal microbiota profiling upon their arrival in laboratory facilities and were found to harbour a variety of pathogens and commensal bacteria (Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 2). Accordingly, pet shop mice had serological profiles that were consistent with the diverse pathogen and microbial exposure typically seen in non-SPF mice18,20,21 (Extended Data Fig. 1).

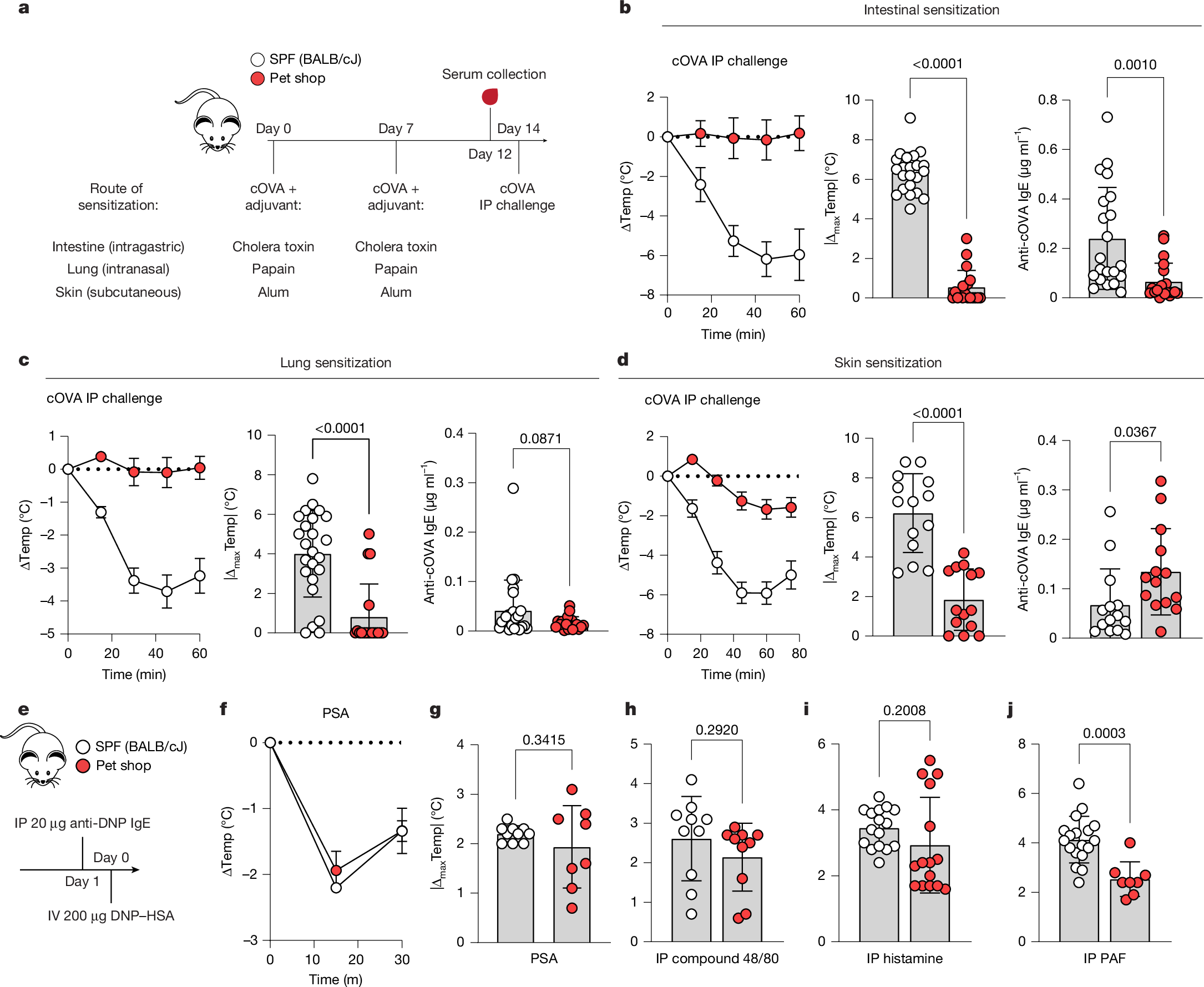

To test allergic sensitization potential, SPF and pet shop mice were exposed to a model allergen—chicken ovalbumin (cOVA)—at three barrier tissue sites with type II-driving adjuvants, and then assayed for anaphylactic responses to systemic cOVA exposure22 (Fig. 1a). Notably, and regardless of sensitization route, pet shop mice were only mildly responsive to allergen challenge, whereas SPF mice underwent severe anaphylactic shock and hypothermia (Fig. 1b–d, left). As a measure of allergic sensitivity, the absolute maximum amount of body temperature lost was calculated for each mouse following systemic challenge (Fig. 1b–d, middle). Pet shop mice produced less antigen-reactive IgE than SPF mice after intestinal or lung exposure, but produced equal or greater amounts of anti-cOVA IgE following subcutaneous exposure (Fig. 1b–d, right). Whereas the protection from anaphylaxis following intestinal or lung exposure may be simply explained by reduced production of IgE, the skin sensitization data suggested that some obstruction of IgE-mediated mast cell activation or an impaired response to mast cell-derived anaphylactogens might be present in the system. To test protection from anaphylaxis at the effector level, we subjected SPF and pet shop mice to passive IgE-dependent or IgE-independent mast cell activation, observing no difference between groups (Fig. 1e–h). Direct provision of the anaphylactogens histamine and platelet activating factor (PAF) showed that pet shop mice had similar, although generally slightly reduced, responses to signals downstream of effector cells (Fig. 1i, j). Therefore, the subdued allergic response seen in pet shop mice after sensitization was not fully accounted for by global defects in anaphylactic potential.

a, Experimental scheme for induction of allergic sensitization. SPF (BALB/cJ) and pet shop mice were administered cOVA by the indicated route with adjuvant on day 0 and day 7, serum was collected on day 12, and mice were challenged intraperitoneally (IP) with cOVA on day 14. b–d, Core temperature (Temp) following systemic cOVA challenge (left), maximal temperature decrease (middle) and cOVA-reactive IgE levels (right) following intestinal sensitization (b; SPF: n = 22; pet shop: n = 19), lung sensitization (c; SPF: n = 24; pet shop: n = 18) or skin sensitization (d; n = 14). e, Experimental scheme for IgE-mediated passive systemic anaphylaxis (PSA). IV, intravenous. f,g, Kinetics of temperature decrease (f) and maximal temperature decrease (g) following challenge with dinitrophenyl–human serum albumin (DNP–HSA) (SPF: n = 10; pet shop: n = 8). h–j, Maximal temperature decrease following intraperitoneal injection of mast cell secretagogue compound 48/80 (h) (n = 10), histamine dihydrochloride (i) (SPF: n = 16; pet shop: n = 15) or PAF-16 (j) (SPF: n = 18; pet shop: n = 8). Data are pooled from two or more repeats of each experiment.

On the basis of these results, we reasoned that protection from active anaphylactic responses may occur upstream of mast cell activation in pet shop mice. Whereas pet shop mice elaborated allergen-reactive IgE levels in line with several inbred SPF strains following skin sensitization, the levels of allergen-reactive IgG1 and IgG2 in pet shop mice were highly elevated, with IgG2 displaying altered kinetics (Extended Data Fig. 2a–d). Although not all inbred SPF strains were equally susceptible to anaphylaxis (Extended Data Fig. 2e), none resembled pet shop mice serologically, highlighting that background genetics alone were unlikely to explain the humoral response in pet shop mice. Across other routes of sensitization, pet shop mice also produced a higher allergen-reactive IgG:IgE ratio than inbred SPF mice (Extended Data Fig. 2f,g). In line with a previous report23, we did not detect elevated serum cytokines at baseline that would influence production of IgG versus IgE, although this might not account for cytokines in the lymph node microenvironment (Extended Data Fig. 3a). We did notice that, at baseline, pet shop mice have appreciable serum mast cell protease 1 (MCPT-1) indicative of ongoing mast cell activation, but MCPT-1 was not increased following anaphylactic challenge (Extended Data Fig. 3b). As further confirmation of protection from anaphylaxis, pet shop mice had a marginal increase in haematocrit following challenge, suggesting that we were not missing anaphylactic events by temperature readouts (Extended Data Fig. 3c).

High levels of allergen-reactive IgG are thought to be the protective mechanism of allergen immunotherapy by binding allergen and preventing engagement with IgE-coated mast cells or by inhibiting mast cell activation via the inhibitory Fc receptor FcRγIIb24,25,26. Transfer of allergen-reactive IgG-rich serum to allergic SPF mice was sufficient to reduce subsequent anaphylaxis, consistent with the notion that the high level of allergen-reactive IgG seen in pet shop mice can be protective (Extended Data Fig. 4a–c). IgG-mediated anaphylaxis can also occur, typically at lower concentrations of antibody than we used in testing passive protection. Administering a smaller dose of antigen-reactive IgG immediately before systemic challenge showed that IgG-mediated anaphylaxis in SPF and pet shop mice was equivalent (Extended Data Fig. 4d–f). Together, these data suggested that pet shop mice, unlike SPF mice, are protected from allergic sensitization by mounting IgG-dominant humoral responses to allergen exposure.

Pet shop mice have prior immune memory

Protection from the allergic state in pet shop mice correlated with alterations in the adaptive immune response towards allergens. Surprisingly, pet shop mice had detectable cOVA-reactive IgG antibodies at baseline (Fig. 2a). As the pet shop mice had no known prior exposure to cOVA, the presence of such antibodies suggested the possibility that an immunostimulatory environment might drive the generation of cross-reactive immunological memory. To better characterize the reactivities, we developed an epitope display tool based on the eCPX (enhanced circularly permuted outer membrane protein OmpX) system27 (Extended Data Fig. 5a,b). Peptide libraries derived from cOVA and ovalbumin (OVA) orthologues from several avian species were generated for panning against antibodies. We tested the epitope display tool using monoclonal antibodies with defined reactivities by flow cytometry (Extended Data Fig. 5c,d) and by next-generation sequencing (Extended Data Fig. 5e), enriching the known epitope regions targeted by each monoclonal antibody and similar epitopes in orthologues. Sera from cOVA-immunized SPF mice enriched multiple cOVA-derived peptides, whereas cOVA-naive SPF mice showed minimal epitope enrichment (Fig. 2b). By contrast, sera from pet shop mice had diverse cOVA epitope enrichment even without prior cOVA immunization (Fig. 2b). This suggested that there may not have been a single antigen in the pet shop environment that gave rise to cOVA cross-reactivity, but rather the sheer accumulated memory repertoire reacted as a ‘stochastic ensemble’ with idiosyncratic sets of cOVA epitopes. To explore cross-reactive antigen space, albeit with reversed directionality, we screened a cOVA-reactive monoclonal antibody originally isolated from a cOVA-immunized mouse28 against a universal peptide epitope library29. We observed a remarkable breadth of reactivity: although the native cOVA epitope (LPGFGD) was detected, it was only the 99th most-enriched epitope (Extended Data Fig. 5f). Additionally, thousands of diverse epitopes gave signal above background, with clear amino acid positional preferences among the most-enriched targets (Extended Data Fig. 5g). However, several strongly enriched epitopes bore no sequence resemblance to the cOVA epitope used to select the original antibody (for example, KAASWA, ranked 325th). The impressive range of reactivities for a single monoclonal antibody lends credence to the idea that in triggering multitudinous immune responses, the pet shop environment might drive the generation of cross-reactive antibodies towards many otherwise novel antigens.

a, cOVA-reactive IgG from sera of unimmunized SPF (C57BL/6J) or pet shop mice (SPF: n = 10; pet shop: n = 15) at 1:100 dilution. b, Epitope profiling of cOVA-reactive IgG in SPF (C57BL/6J) and pet shop mice with or without cOVA exposure (n = 6 baseline; 10 immunized). Each row represents one sample. FC, fold change. c, Representative ELISpot images of IFNγ+ splenocytes from the indicated sources incubated without antigen or with cOVA or KLH. d–f, Quantification of IFNγ+ spots at baseline (d) and after incubation with cOVA (e) or KLH (f) (SPF unimmunized: n = 8; SPF KLH: n = 8; pet shop unimmunized: n = 9). Colours as indicated in c. g, Representative flow cytometry plots of CD4+CD154+ T cells from the indicated sources following incubation with or without cOVA. h, Background-corrected quantification of IFNγ+CD4+ T cells after incubation with cOVA (SPF: n = 11; pet shop: n = 12). Two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test (a,h) or one-way ANOVA with Tukey correction for multiple comparisons (d–f). Error bars represent s.d. Data are pooled from two or more repeats of each experiment or representative of two experiments (b).

Using our epitope display system, we were also interested in characterizing the fine reactivities of additional inbred SPF strains following cOVA immunization. The targeted epitopes appeared to be strain-dependent with potential genetic and environmental contributions (Supplementary Fig. 3a,b). Unexpectedly, mouse strains with shared MHC haplotypes had divergent epitope preferences (Supplementary Fig. 3b–e). It therefore seems plausible that several layers of selection shape the constellation of antibody reactivities seen in particular strains or housing conditions. Overall, these data suggested that the presence of pre-existing cOVA-reactive antibodies in pet shop mice was dependent on the environment, whereas the fine reactivities probably depended on both the antigenic stimulus and individual genetics.

As the formation of most IgG antibodies requires T cell help, we next investigated the T cell compartment in pet shop mice. Given the apparent promiscuity of memory T cell responses in adult humans30, it seemed possible that T cells in pet shop mice might not be immunologically naive to the model allergens used in sensitization experiments. To characterize T cell recognition of model antigens prior to immunization, we screened splenocytes from unimmunized pet shop and SPF mice, as well as SPF mice immunized with keyhole limpet haemocyanin (KLH), for cytokine production in response to antigen via enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISpot) assay. Whereas naive SPF mice, as expected, exhibited essentially no IFNγ production in response to cOVA or KLH, pet shop mice showed robust production of IFNγ after incubation with either antigen (Fig. 2c–f). We also tested for IL-4 and found negligible antigen-reactive type II memory cells in pet shop mice (Extended Data Fig. 6). These data suggested that pet shop mice had type I cOVA and KLH-reactive memory cells despite the mice never having encountered such antigens in their life histories. Substantiating this finding, progeny from pet shop mice born and raised in laboratory facilities produced mixed type I/type II humoral responses after adulthood sensitization with KLH in alum analogous to cOVA responses (Supplementary Fig. 4). As IFNγ is a major driver of B cell class-switching to IgG2 antibody subclasses31, pre-existing, antigen-reactive memory T cells producing IFNγ may explain the mixed type I/type II antibody production in pet shop mice following antigen exposure in alum. An orthogonal flow cytometry-based approach32 further confirmed the presence of cOVA-reactive memory CD4+ T cells in unimmunized pet shop mice (Fig. 2g,h and Supplementary Fig. 5). These data are consistent with findings in humans30,33,34,35 and suggest a possible adaptive immune mechanism by which allergic sensitization is temporally biased to the early-life period by virtue of limited cumulative immune experience.

A perinatal window for allergy

It is generally appreciated that, through an unknown mechanism, adult human immune responses to alum-based vaccines yield mixed type I/type II memory, in contrast to the strongly type II-polarized responses seen in infants after identical vaccination36,37. The peculiar production of antigen-reactive IgG2 antibodies (subclasses associated with type I immunity