Early hominins from Morocco basal to the Homo sapiens lineage

TL;DR

New hominin fossils from Morocco, dated to around 773 ka, show a mix of primitive and derived traits, supporting an African lineage ancestral to Homo sapiens and offering clues about the last common ancestor with Neanderthals and Denisovans.

Key Takeaways

- •Fossils from Thomas Quarry I in Morocco, dated to approximately 773 ka, provide evidence for an African population basal to the Homo sapiens lineage.

- •These hominins exhibit a combination of primitive features and derived characteristics reminiscent of later H. sapiens and Eurasian archaic hominins.

- •The findings challenge Eurasian origin theories and highlight the importance of African hominin diversity during the late Early Pleistocene.

- •The fossils offer insights into the last common ancestor shared with Neanderthals and Denisovans, dated around 765–550 ka.

- •Magnetostratigraphy and biochronological data confirm the age, aligning with the Matuyama–Brunhes transition and supporting a well-dated context.

Tags

Abstract

Palaeogenetic evidence suggests that the last common ancestor of present-day humans, Neanderthals and Denisovans lived around 765–550 thousand years ago (ka)1. However, both the geographical distribution and the morphology of these ancestral humans remain uncertain. The Homo antecessor fossils from the TD6 layer of Gran Dolina at Atapuerca, Spain, dated between 950 ka and 770 ka (ref. 2), have been proposed as potential candidates for this ancestral population3. However, all securely dated Homo sapiens fossils before 90 ka were found either in Africa or at the gateway to Asia, strongly suggesting an African rather than a Eurasian origin of our species. Here we describe new hominin fossils from the Grotte à Hominidés at Thomas Quarry I (ThI-GH) in Casablanca, Morocco, dated to around 773 ka. These fossils are similar in age to H. antecessor, yet are morphologically distinct, displaying a combination of primitive traits and of derived features reminiscent of later H. sapiens and Eurasian archaic hominins. The ThI-GH hominins provide insights into African populations predating the earliest H. sapiens individuals discovered at Jebel Irhoud in Morocco4 and provide strong evidence for an African lineage ancestral to our species. These fossils offer clues about the last common ancestor shared with Neanderthals and Denisovans.

Similar content being viewed by others

New reconstruction of DAN5 cranium (Gona, Ethiopia) supports complex emergence of Homo erectus

The relevance of late MSA mandibles on the emergence of modern morphology in Northern Africa

Origins of modern human ancestry

Main

Our understanding of the evolutionary history of both Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis) and H. sapiens is firmly grounded in morphological, genetic and archaeological analyses of extensive fossil hypodigms and numerous prehistoric sites across Europe and Africa. However, identifying the last common ancestor of these two species remains challenging. At times, Homo heidelbergensis was proposed as this ancestor5. Yet, anatomical and chronological evidence suggests that fossils assigned to H. heidelbergensis may not represent a coherent species6. Most of the Eurasian specimens assigned to this species probably belong to the common ancestral form of the Neanderthals and their Asian sister group, the Denisovans, or belong to them, but are not ancestral to H. sapiens6. Some have considered a Eurasian origin of H. sapiens7, but the morphological evidence for this is limited. By contrast, recent fossil evidence has pushed back the presence of H. sapiens in Africa to over 300 ka (ref. 4), highlighting the need to understand hominin diversity in Africa during the late Early Pleistocene (EP) and the first half of the Middle Pleistocene (MP). MP African fossils—such as those from Kabwe (Zambia), Bodo (Ethiopia) and Saldanha (South Africa)—are generally considered close African relatives of H. heidelbergensis (or Homo rhodesiensis). Among MP African specimens, those from Ndutu (Tanzania) and Salé (Morocco) have been more closely associated with the ancestry of H. sapiens8.

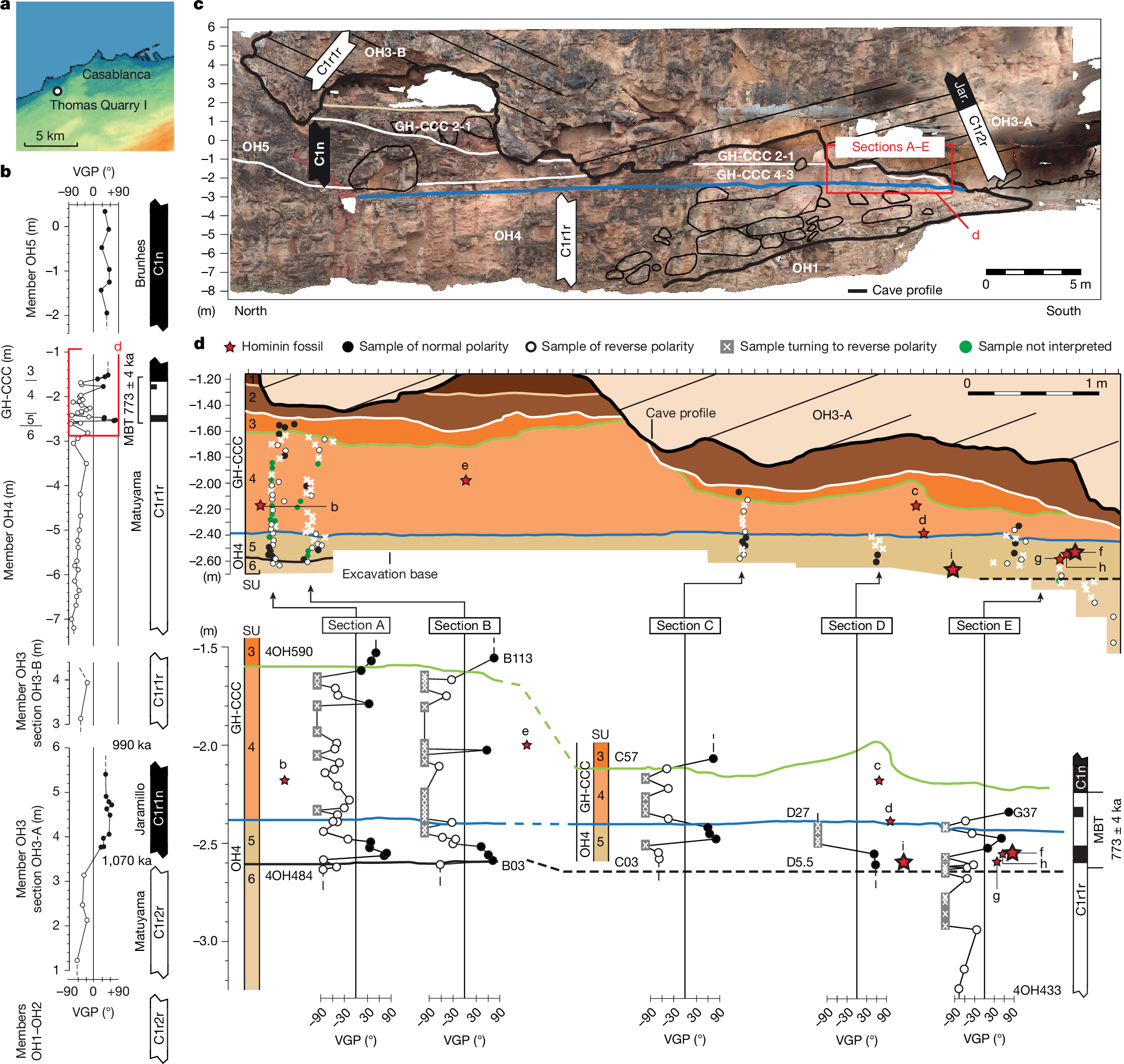

Thomas Quarry I (ThI), located in the southwest part of the city of Casablanca, Morocco (Fig. 1a), represents a key archaeological locality in northwest Africa. ThI is excavated in the Oulad Hamida Formation (OHF)9,10 and comprises two primary sites (Extended Data Figs. 1 and 2a).

a, Location map of ThI, modified according to ref. 13. b, Magnetostratigraphy of members OH3A, OH3B, OH4, GH-CCC and OH5 of ref. 13 and this study. The black bars represent normal polarity, and the white bars represent reverse polarity. Further details are provided in Supplementary Fig. 2. Magnetochron ages are from ref. 22. c, Photograph of the outcrop stratigraphy with indication of magnetic polarity from this study and a previous study13 and lithologic members. Here we focused on sections A–E, of which only section A is reported here. d, Magnetostratigraphy of sections A–E comprised stratigraphic units OH4 SU6–5 and GH-CCC SU4–3. Context and details for lithostratigraphic units are provided in Extended Data Fig. 2. The red stars with labels represent hominin remains (the larger stars indicate mandibles) (Extended Data Table 1): ThI-GH-UA28-7 (femur, a); ThI-GH-OA23-24 (tooth, b); ThI-GH-SA26-88 (tooth, c); ThI-GH-SA26-90 (tooth, d); ThI-GH-PA24-107 (tooth, e); ThI-GH-10717 (mandible) and ThI-GH-10717/1-5 (vertebrae, f); ThI-GH-10725 and ThI-GH-10725/1 (vertebrae, g); ThI-GH-10726 (vertebra, h); and ThI-GH-10978 (mandible, i). Note that ThI-GH-UA28-7 (a) is located outside the section on the right. Close to the bottom wall of the cavity, its insertion into the stratigraphy is imprecise (SU4/5).

In the oldest member of the OHF, the ThI-L site has yielded one of the most extensive early Acheulean lithic assemblages in Africa, dating back to around 1.3 million years ago11,12,13. The second site is a cave opened in the northeastern wall of the quarry named in 1994 Grotte à Hominidés (hereafter, ThI-GH) by the research team. In 1969, Philippe Beriro, an amateur collector, found a partial hominin mandible (ThI-GH-1) (Fig. 2) on a slope below the northwestern part of this cave, along with other mammal fossils and lithics. This material probably originated from the filling of the ThI-GH cave, which had been partially disturbed by quarrying activities14,15. ThI-GH-1 was initially described as Atlanthropus mauritanicus16. Subsequent systematic investigations at ThI-GH, carried out between 1994 and 2015, yielded an Acheulean industry, a diverse faunal assemblage and several additional hominin fossils in an undisputable stratigraphic context thanks to modern controlled excavations17,18,19.

Mandible ThI-GH-1: (1) lateral view; (2) occlusal view; (3) lingual view. Mandible ThI-GH-10717: (4) right lateral view; (5) occlusal view. Mandible ThI-GH-10978: (6) lateral view; (7) lingual view. UP4 ThI-GH-OA23-24: (8) distal view; (9) mesial view. UP3 ThI-GH-PA24-107: (10) distal view; (11) mesial view. UP3 ThI-GH-SA26-90: (12) mesial view; (13) distal view. UI1 ThI-GH-SA26-88: (14) buccal view; (15) lingual view. (16) Fused C2 and C3 vertebrae ThI-GH-10725 and ThI-GH-10725/1, caudal view. (17) C4 vertebra ThI-GH-10717/5, cranial view. (18) C6 vertebra ThI-GH-10717/1, cranial view. (19) C7 vertebra ThI-GH-10717/3, cranial view. (20) T1 vertebra ThI-GH10717/2, cranial view. (21) T2 vertebra ThI-GH-10717/4, cranial view. Scale, 5 cm.

ThI-GH is a cave that was carved during a marine high-stand into the older marine-aeolian OH1 and OH3 deposits of the OHF. It was filled by marine (OH4 stratigraphic unit 6, SU6) then supratidal (SU5) deposits and, without any discontinuity, by continental deposits (GH-CCC SU4 and SU3). Then, aeolian deposits (OH5) separated the latter from upper continental deposits (SU2 and SU1)10,18 (Fig. 1c, Extended Data Fig. 2, Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Fig. 3). A rich palaeontological assemblage has been recovered from OH4 SU5 and GH-CCC SU4, with hominin remains and lithic artifacts17,18,19,20 (Extended Data Fig. 3a,b and Supplementary Notes 2 and 3). The abundance of carnivores, numerous coprolites and carnivore-modified bone remains lacking evidence of cut or chop marks, combined with the scarcity of lithic artifacts, point to the presence of a carnivore den21 (Supplementary Note 2). The most representative hominin specimens have been found in SU5, including an adult mandible (ThI-GH-10717), eight associated vertebrae (ThI-GH-10717/1 to 5, ThI-GH-10725, ThI-GH-10726 and ThI-GH-10725/1) and a fragmentary mandible (ThI-GH-10978) of a child who died aged at most 1.5 years (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Note 7). A portion of a hominin femoral shaft (ThI-GH-UA28-7) scavenged by a large carnivore, probably a hyena21, was found at the back of the cavity in a layer belonging to SU4 or SU5. Although the precise stratigraphic origin of the ThI-GH-1 hemimandible remains uncertain, sedimentological analysis of the embedding sediment suggests that it also probably derives from either SU4 or SU5 (ref. 18).

Dating

We proposed a chronostratigraphic and depositional model for the OHF within a sequence stratigraphy framework shaped by Pleistocene sea-level fluctuations and moderate regional uplift9,10,13. Sea-level transgressive phases mark calcarenite onlap and the carving of cliff and erosional notch at the base of previously lithified aeolian dunes, whereas regressive phases involve seaward progradation and the buildup of new dunes. Early cementation in semiarid, bioclastic-rich coastal settings allows rapid lithification9, enabling successive transgressive erosion and cliff formation (Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Fig. 2). A previous study13 placed the Matuyama–Brunhes transition (MBT, 773 ka)22 close to the base of SU4 and recognized the Jaramillo subchron (1,070–990 ka) in member OH3. This interpretation excludes hiatus long enough to imply older subchrons like the Olduvai in place of the Jaramillo, which would also contradict the Acheulean lithics found at ThI-L. However, the preliminary sampling within the GH-CCC SU4 and OH4 SU5 deposits containing the human remains (five samples in section A) did not allow precise placement of the MBT in relation to these remains. We refined this model by adding 119 new magnetostratigraphic samples (Methods and Supplementary Note 5) from OH3, OH4 and GH-CCC to the 62 from ref. 13, improving the resolution of the Jaramillo and the MBT22 (Fig. 1b,c).

Characteristic remanent magnetization (ChRM) component directions of samples from two different sections yielded virtual geomagnetic pole (VGP) latitudes indicating that the Jaramillo subchron lies within member OH3. Most of the samples from SU6 to SU3 (Fig. 1c,d (sections A–E)) provided VGP latitudes of reverse magnetic polarity or ChRM directions showing a tendency towards reverse polarity (Supplementary Note 5). This post-Jaramillo interval of dominant reverse polarity is punctuated by a thin normal polarity excursion in SU5. Above, a reverse-to-normal polarity transition occurs in GH-CCC close to the SU4–SU3 contact, with stable normal (Brunhes) polarity extending into GH-CCC-SU3 (Fig. 1d) and continuing into younger OH5 deposits (Fig. 1c).

These results reveal a detailed recording of the MBT occurring throughout SU6 to SU3. In records of high sediment accumulation rate (>15 cm per thousand years), the MBT is characterized by brief VGP excursions occurring between stable reverse (Matuyama) and stable normal (Brunhes) polarity23,24, with a mid-point at 773 ka and a transition duration of around 8 or 10.8 thousand years23,24. Our sampling probably captured one such excursion in OH4-SU5 (Fig. 1b,d and Extended Data Fig. 4). The intertidal biocalcarenites of SU6 and the littoral sands of SU5 are interpreted as representing the marine isotope stage (MIS) 20–MIS19 transgression of sea-level (starting at around 795 ka)25 and the subsequent maximum flooding surface, respectively. The continental deposits of SU4–SU3 are interpreted as part of the ensuing regressive system tract associated with the MIS19 highstand (around 780 ka). This is consistent with a sedimentation rate of around 20 cm per thousand years, largely sufficient to capture the MBT variability. As in the Gran Dolina TD6 layer (Sierra de Atapuerca)2, our analysis indicates hominin ages younger than 990 ka (top of Jaramillo) and close to the MBT at a nominal age of 773 ± 4 ka (ref. 23) (Fig. 1d and Extended Data Fig. 4).

Biochronological data closely agree with the magnetostratigraphic ones (Supplementary Note 2). The fauna includes 37 species of mammals; it shares many species with that of Tighennif in Algeria, at least 1 million years old26. It documents the last known occurrences of the hare Trischizolagus and of the rhino Ceratotherium mauritanicum; Theropithecus oswaldi and Kolpochoerus are also indicative of an early age. Comparisons with other African sites are in good agreement with an age close to the EP–MP boundary20,27. Resemblances with East and South African faunas attest to easy latitudinal exchanges, demonstrating that the Sahara was not a permanent barrier in EP times owing to the recurrent expansion of savanna landscapes across North Africa in response to short-lived, astronomically driven periods of enhanced monsoon rainfall28,29.

Optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) dating, performed in unit SU4 on cemented sands provided age estimates of 420 ± 34 ka and 391 ± 32 ka (refs.