Insights into DNA repeat expansions among 900,000 biobank participants

TL;DR

Analysis of DNA sequencing data from over 900,000 participants reveals that tandem DNA repeats exhibit variable germline and somatic instability, with genetic modifiers influencing expansion rates and associations with diseases like chronic kidney disease.

Key Takeaways

- •DNA repeats show wide variability in germline and somatic mutation rates across different loci and tissues, with some like TCF4 highly unstable in blood.

- •Genetic modifiers identified through genome-wide association studies affect somatic expansion rates, with polygenic scores showing up to fourfold variation in instability.

- •Expanded repeats in the GLS gene are linked to increased risks of chronic kidney disease and liver diseases, highlighting clinical implications.

- •Repeat interruptions significantly stabilize alleles, reducing expansion rates, as observed in TCF4 and GLS repeats.

- •The study uses computational methods to analyze large biobank data, providing insights into repeat dynamics across the human lifespan.

Tags

Abstract

Expansions and contractions of tandem DNA repeats generate genetic variation in human populations and in human tissues. Some expanded repeats cause inherited disorders and some are also somatically unstable1,2. Here we analysed DNA sequencing data from over 900,000 participants in the UK Biobank and the All of Us Research Program using computational approaches to recognize, measure and learn from DNA-repeat instability. Repeats at different loci exhibited widely variable tissue-specific propensities to mutate in the germline and blood. Common alleles of repeats in TCF4 and ADGRE2 exhibited high rates of length mosaicism in the blood, demonstrating that most human genomes contain repeat elements that expand as we age. Genome-wide association analyses of the extent of somatic expansion of unstable repeat alleles identified 29 loci at which inherited variants increased expansion of one or more DNA repeats in blood (P = 5 × 10−8 to 2.5 × 10−1,438). These genetic modifiers exhibited strong collective effects on repeat instability: at one repeat, somatic expansion rates varied fourfold between individuals with the highest and lowest 5% of polygenic scores. Modifier alleles at several DNA-repair genes exhibited opposite effects on the blood instability of the TCF4 repeat compared with other DNA repeats. Expanded repeats in the 5′ untranslated region of the glutaminase (GLS) gene associated with stage 5 chronic kidney disease (odds ratio (OR) = 14.0 (5.7–34.3, 95% confidence interval (CI))) and liver diseases (OR = 3.0 (1.5–5.9, 95% CI)). These results point to complex dynamics of DNA repeats in human populations and across the human lifespan.

Similar content being viewed by others

Inherent instability of simple DNA repeats shapes an evolutionarily stable distribution of repeat lengths

A phenome-wide association study of tandem repeat variation in 168,554 individuals from the UK Biobank

Human de novo mutation rates from a four-generation pedigree reference

Main

Short tandem repeats (STRs) of 1–6 bp of DNA are mutable genomic elements with diverse influences on cellular and organismal phenotypes2. Common STR polymorphisms, which have been characterized in human populations using short-read3 and long-read4 sequencing, influence gene expression5 and complex traits6,7. Rare STR expansions cause more than 60 genetic disorders1. The allelic diversity that underlies these effects is generated by frequent mutation: around 1 million polymorphic STRs in the human genome generate around 50–60 de novo repeat-length mutations per offspring8,9,10. Germline mutation rates of specific STRs vary widely11 and are influenced by repeat motif sequence, interruptions of pure repeats and number of repeat units8,9,10,11,12 as well as genetic variation in DNA-repair genes9.

STRs are also prone to somatic mutation2, and lifelong somatic expansion in at least one STR locus can lead to disease. Recently, genome-wide association studies (GWASs) have provided insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying somatic repeat instability13 by finding common genetic modifiers of the timing or progression of Huntington’s disease (HD)14,15,16,17,18,19, which is caused by inherited alleles in which a CAG repeat in the HTT gene is longer than 35 CAGs; these genetic modifiers were found in many DNA-repair genes that affect the stability of DNA repeats14,15,16,17,18,19. Neurodegeneration in HD was subsequently found to be caused by somatic expansion of this repeat beyond a high threshold of about 150 CAG repeats20. The genetic-modifier studies, so far of up to 16,640 persons with HD, have provided early clues toward a few potential therapeutic targets for slowing or halting somatic expansion of DNA repeats; however, the number of such potential targets is so far modest.

Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) of biobank cohorts offers opportunities to study repeat instability in much larger sample sizes than previously possible. Here we analysed repeat instability at 356,131 polymorphic repeat loci using short-read WGS data from the blood-derived DNA of 490,416 participants in UK Biobank (UKB)21 and 414,830 participants in All of Us (AoU)22. To do so, we developed several computational techniques, overcoming challenges in estimating the length and instability of DNA repeats from large numbers of short WGS reads23. These methods enabled us to characterize allele-specific expansion and contraction rates of common repeats, identify genetic influences on somatic repeat expansion and identify associations of expanded repeats with diseases.

CAG-repeat expansions in the UKB

We began by analysing CAG trinucleotide repeats, which we could efficiently ascertain from biobank sequencing data and which cause many progressive, neurodegenerative repeat-expansion disorders1,2. We identified UKB participants with long CAG-repeat alleles (≥45 repeat units) by analysing WGS data for 151 bp sequencing reads comprised entirely or almost entirely of CAG-repeat units (in-repeat reads (IRRs); Extended Data Fig. 1a). Such reads were easily extractable, as nearly all of them had been aligned to the TCF4 CAG-repeat sequence by bwa24 (Supplementary Fig. 1). For each participant with one or more IRRs, we determined the locus or loci from which the IRRs originated by identifying mate sequences that mapped near one of 1,159 commonly polymorphic CAG-repeat loci3.

The vast majority of CAG-repeat expansions in the UKB occurred at only a few loci: 18 autosomal CAG-repeat sequences in the human genome were expanded to at least 45 repeat units in at least five UKB participants (Extended Data Fig. 1b and Supplementary Table 1). Three repeat loci were expanded in thousands of UKB participants—CA10 (137,673 participants), TCF4 (42,004) and ATXN8OS (7,736)—together accounting for 97% of all observed expansions beyond 45 repeat units. Most of these repeats (15 out of 18) were in transcribed genomic regions, consistent with the idea that transcription contributes to repeat instability25 (Supplementary Table 2). For 9 out of the 18 repeats, expanded alleles are known to be pathogenic1.

To study the mutability of these repeats, we measured the lengths of common, short alleles of each repeat (≤30 repeat units) by analysing sequencing reads that spanned repeat alleles, focusing on 15 repeat loci that passed additional filters (Extended Data Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 1). These analyses recovered repeat-length distributions consistent with previous analyses26 (Extended Data Fig. 1b).

Germline instability of common CAG repeats

We first analysed germline instability of these repeats, using the large UKB cohort to obtain high-resolution estimates of germline mutability (providing context for analyses of somatic mutability). To estimate allele-specific intergenerational expansion and contraction rates of each repeat, we analysed length discordances among alleles belonging to genomic tracts inherited identical-by-descent (IBD) from shared ancestors, building on IBD-based analyses of single-nucleotide mutations27,28,29 (Fig. 1a). We validated this approach using two complementary methods (Supplementary Fig. 2).

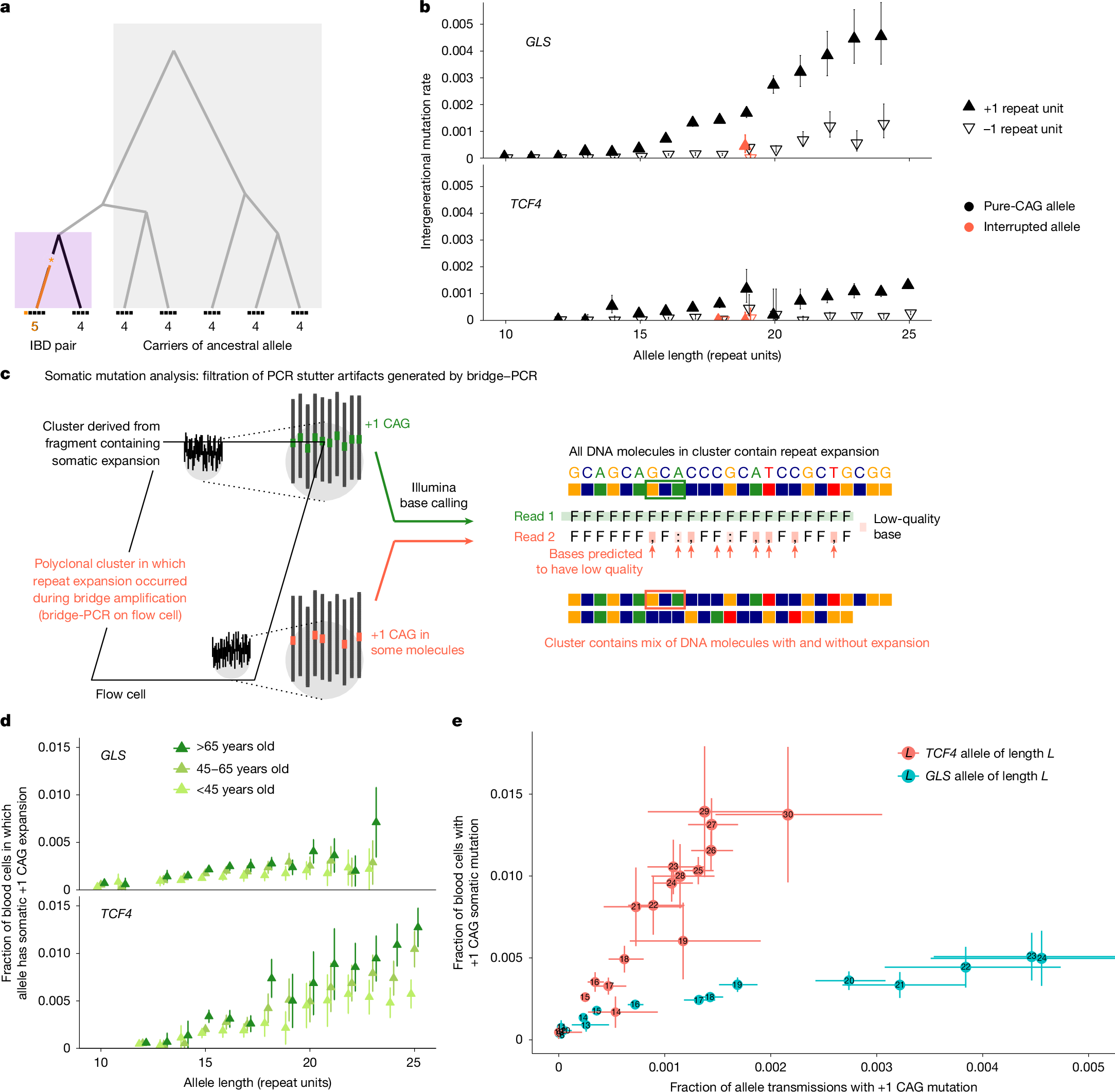

a, Germline mutation rates were estimated by analysing discordance rates among alleles inherited within IBD tracts shared by pairs of UKB participants. Ancestral alleles were imputed from more-distantly shared haplotypes. b, Per-generation rates of germline expansion (+1 repeat unit) and contraction (−1 repeat unit) of GLS and TCF4 repeat alleles, estimated in the UKB. c, The analytical strategy for estimating somatic mutation rates by detecting and filtering out reads that are likely to reflect PCR artifacts introduced during sequencing. During PCR-based bridge amplification on a flow cell, a DNA fragment is clonally amplified into a cluster of colocalized DNA molecules. A PCR stutter error results in a polyclonal cluster containing a mixture of DNA molecules with and without the error. If the molecules containing the error constitute the majority of the cluster, the sequencing read generated from the cluster (reflecting the majority base at each position within the read) will contain the error, but the heterogeneity of the cluster will reduce base qualities at positions within the read that mismatch between molecules with and without the error. d, The rates of somatic expansion of GLS and TCF4 repeat alleles (that is, the fractions of blood cells in which an allele has expanded by +1 repeat unit), stratified by age in AoU. e, Somatic mutation rates in the UKB plotted against germline mutation rates for GLS and TCF4 repeat alleles. The error bars show the 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Sample sizes are provided in Supplementary Table 3.

Across all 15 CAG-repeat loci, intergenerational mutation rates increased with allele length, rising to 0.5–0.9% per generation for single-repeat-unit expansions of the longest common alleles of repeats in GLS, DMPK and ATXN8OS (Extended Data Figs. 1b and 2). The average mutation rate per locus ranged from 8.2 × 10−5 to 9.5 × 10−4 (Supplementary Table 3). These rates are relatively high for trinucleotide repeats8 and exceed the genome-wide average for STRs (around 5 × 10−5 per haplotype per generation)8,9,10. Repeat loci tended to either expand more often than contract (particularly so for ATXN8OS and GLS) or to have similar expansion and contraction rates (Extended Data Figs. 1b and 2). Interruptions of repeat sequences (that is, intrarepeat sequence variants) greatly stabilized alleles: a common 18-repeat TCF4 allele containing an interruption in its ninth repeat unit exhibited a 135-fold (54–336, 95% CI) lower expansion rate compared with the uninterrupted 18-repeat allele, and an interruption in the second-to-last repeat unit of a 19-repeat GLS allele decreased the expansion rate 3.7-fold (1.9–7.2, 95% CI) (Fig. 1b). These results corroborate previous observations that repeat interruptions stabilize the expansion of pathogenic alleles30,31,32 and quantify the strength of such effects in the germline.

Somatic expansion of common CAG repeats

These high rates of germline instability led us to wonder whether common alleles of some repeats might be sufficiently unstable in blood cells for somatic length-change mutations to be ascertainable in short-read WGS data. Identifying such mutations is challenging because polymerase slippage during PCR amplification can spuriously alter repeat lengths33,34,35. Such ‘PCR stutter’ errors are unavoidable during Illumina sequencing by synthesis, which uses PCR for bridge amplification of DNA fragments36. However, we realized that this PCR error mode tends to produce predictable patterns of reduced base quality scores within sequencing reads, enabling us to detect and exclude most reads with artefactual CAG length mutations (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 3). We applied this filtering strategy in the UKB to estimate repeat-specific, allele-specific somatic expansion rates, which we quantified as the average fraction of blood cells in which a given repeat allele has expanded by one repeat unit.

For 4 out of the 15 CAG repeats (in TCF4, GLS, DMPK and ATN1), we detected significant increases in somatic single-repeat-unit expansion rates with age (Extended Data Fig. 3). These findings were replicated in AoU, in which the wider age range of participants (aged 18 to 90+ years) revealed clear increases in fractions of blood cells containing somatic expansions with increasing age and with increasing allele length (Fig. 1d and Extended Data Fig. 4). TCF4 repeats were the most somatically unstable: individuals carrying alleles with 25 or more repeat units typically exhibited somatic expansion in more than 1% of blood cells by the age of 55 years (Fig. 1d). We did not observe age-associated contraction of any of the 15 repeat loci.

Comparing these estimates of somatic one-repeat-unit expansion rates with our estimates of intergenerational mutation rates showed that the relative (blood/germline) rates of CAG-repeat expansion varied severalfold across repeat loci (Fig. 1e). The TCF4 repeat exhibited the greatest somatic instability in blood but was relatively stable in the germline, whereas the GLS repeat displayed the opposite behaviour (Fig. 1e), as did the DMPK repeat (Extended Data Figs. 1b, 2 and 4). These results align with observations that somatic instability of pathogenic repeat expansions is highly tissue-specific, perhaps due to differences in transcription or trans-acting factors25,37,