Disease tolerance and infection pathogenesis age-related tradeoffs in mice

TL;DR

A study in mice reveals that disease tolerance mechanisms, particularly the Foxo1-Trim63 axis in the heart, function protectively in young hosts during sepsis but become pathogenic in aged hosts. This demonstrates antagonistic pleiotropy, where genes beneficial early in life can be harmful later, impacting infection outcomes and therapy strategies.

Key Takeaways

- •Disease tolerance, a defense strategy limiting infection damage without killing pathogens, changes with age, showing distinct survival paths in young vs. aged mice.

- •In young mice, cardiac Foxo1 and Trim63 protect against sepsis-induced cardiac remodeling and mortality, but in aged mice, they drive pathogenesis and death.

- •The study uses an LD50 polymicrobial sepsis model to show that age-related physiological changes lead to different disease courses despite identical pathogen exposure.

- •Findings suggest that disease tolerance genes exhibit antagonistic pleiotropy, with implications for age-tailored therapies in infectious diseases.

Tags

Abstract

Disease tolerance is a defence strategy essential for survival of infections, limiting physiological damage without killing the pathogen1,2. The disease course and pathology an infection may cause can change over the lifespan of a host due to the structural and functional physiological changes that accumulate with age. Because successful disease tolerance responses require the host to engage mechanisms that are compatible with the disease course and pathology caused by an infection, we predicted that this defence strategy would change with age. Animals infected with a 50% lethal dose (LD50) of a pathogen often show distinct health and sickness trajectories due to differences in disease tolerance1,3 and can be used to define tolerance mechanisms. Here, using a polymicrobial sepsis model, we found that, despite having the same LD50, aged and young susceptible mice showed distinct disease courses. In young survivors, cardiac Foxo1 and its downstream effector Trim63 (MuRF1) protected from sepsis-induced cardiac remodelling, multi-organ injury and mortality. Conversely, in aged hosts, Foxo1 and Trim63 acted as drivers of sepsis pathogenesis and death. Our findings have implications for the tailoring of therapy to the age of an infected individual and indicate that disease tolerance genes show antagonistic pleiotropy.

Main

The immune system is a critical determinant of host survival, enabling resistance to infections and maintenance of tissue integrity. However, the activation of immune responses is inherently associated with costs, necessitating precise regulation to achieve the optimal balance between the benefits and costs of mounting an immune response. The theory of antagonistic pleiotropy, first proposed in the context of evolutionary biology, suggests that traits beneficial to early-life fitness can incur costs that manifest later in life, after the period of strongest natural selection4. Traits that enhance immune resistance, such as heightened inflammatory responses, may provide survival and fitness advantages during reproductive years but contribute to chronic inflammation, autoimmunity and tissue degeneration in organisms later in life5,6. As a consequence, the immune system demonstrates how evolutionary pressures for early-life survival can embed long-term liabilities within host defence programmes. Antagonistic pleiotropy provides a compelling evolutionary framework for understanding why defence responses that once protected us may contribute to declining health later in life.

Beyond resistance, host defences also include cooperative strategies that mitigate infection-induced damage while having a neutral to positive impact on pathogen fitness. These include anti-virulence responses, which limit harmful pathogen and host-derived signals, and disease tolerance mechanisms, which protect from physiological damage by changing how the host responds to damage signals1,2,7. Whether cooperative defence alleles impose costs for the host and are themselves subject to antagonistic pleiotropy is unknown.

A consideration of the specificity of disease tolerance mechanisms shows the further complexities ageing introduces for cooperative defences. The specificity of disease tolerance is defined by the physiological perturbations or pathology that may occur in response to the infection, which can change with age1,8,9,10,11. These differences stem from age-related structural and functional changes in host physiology, which can alter both the nature and severity of pathology during infection. As a result, hosts of different ages may show distinct disease courses despite infection with the same pathogen. It would then follow that the disease tolerance mechanisms required for survival hosts may become maladaptive or incompatible in older individuals, contributing to increased susceptibility to infection-related pathologies, supporting the possibility that disease tolerance alleles show antagonistic pleiotropy.

Here, we use a polymicrobial sepsis model and a 50% lethal dose (LD50)-based framework to define how ageing alters host–pathogen cooperation and disease tolerance. We find that the Foxo1–Trim63 axis mediates a protective cardiac tolerance programme in young hosts but drives pathogenic remodelling in aged hosts. These findings reveal an age-dependent shift in the evolutionary function of disease tolerance mechanisms, highlighting antagonistic pleiotropy as a key principle linking ageing to infectious disease outcomes.

LD50 approach to disease tolerance

To investigate the role of disease tolerance at different life stages, we applied the phenomenon of LD50 to our study. LD50 describes the dose of a pathogen that kills 50% of a genetically identical host population. We previously demonstrated that this phenomenon can be used to elucidate mechanisms of host–pathogen cooperation3. For the present study, we used a polymicrobial sepsis model consisting of a 1:1 mixture of the gram-negative bacterium Escherichia coli and the gram-positive bacterium Staphylococcus aureus in 12-week-old (20–30 years equivalent for humans) and 75-week-old (56–69 years equivalent for humans) mice12, which we call ‘young’ and ’aged’, respectively, for the purposes of this study. We used this infection model because these two bacteria represent some of the most common gram-negative and gram-positive agents that cause sepsis in humans13. We used these two age groups because they allowed us to capture age-associated physiological changes (Extended Data Fig. 1a–q) while avoiding the increased frailty and non-specific mortality that can confound infection studies in more advanced age. We found the LD50 dose for polymicrobial sepsis in both young and aged mice to be roughly 1 × 108 total colony forming units (CFU) (Fig. 1a,b and Extended Data Fig. 1r), suggesting that lethality does not increase with age for this infection at the ages examined.

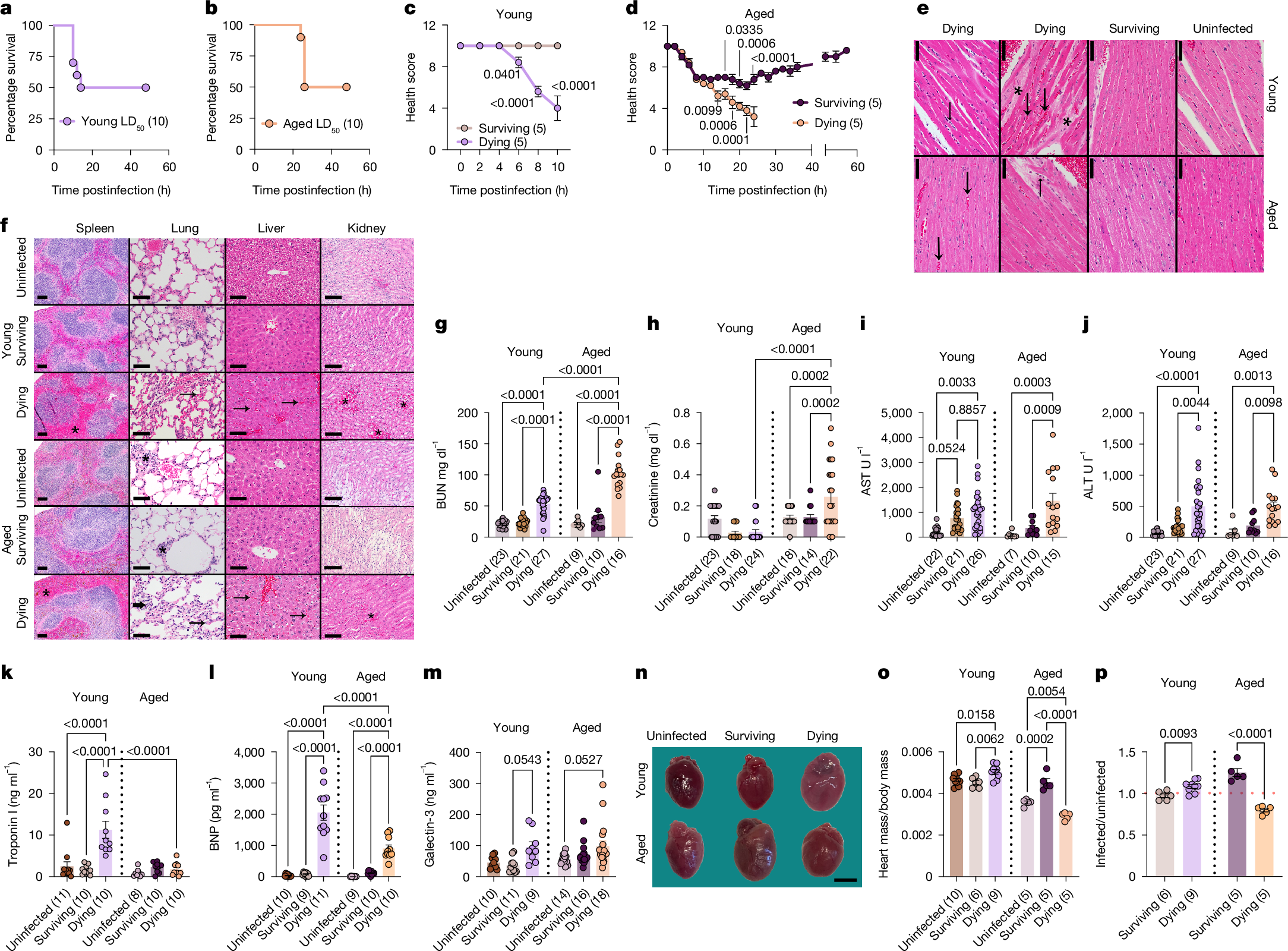

a,b, Young (a) and aged (b) LD50 survival. c,d, Young (c) and aged (d) LD50 health trajectories. Individual data points in Extended Data Fig. 2c,f. n (in parentheses) shows biologically independent animals from one out of three independent experiments (a–d). e, Representative heart images at the interventricular septum. Prominent myocardial vessels in dying. Increased red blood cells (congestion, large arrows), leukocytes (small arrows), mildly increased hypereosinophilic cardiomyocytes, oedema (asterisks). f, Representative images of spleen (scale bar, 100 μm); lung (scale bar, 50 μm); liver (scale bar, 50 μm) and kidney (scale bar, 100 μm). Dying mice have expanded splenic red pulp (congestion, asterisks); increased congestion, leukocyte infiltration in lung interstitium (arrows); increased sinusoidal congestion in liver (arrows); increased congestion in kidney medulla (asterisks). Some aged lungs, have perivascular and peribronchiolar lymphoid aggregates (asterisk) as incidental findings. Two independent experiments were performed (e,f). g, BUN. h, Creatinine. i, AST. j, ALT. For g–j, n shows biologically independent animals from three out of three (aged) or four out of four (young) independent experiments. k, Troponin I. l, BNP. For k,l, n shows biologically independent animals from two out of two independent experiments. m, Galectin-3. n shows biologically independent animals from two out of two (young) and three out of three (aged) independent experiments. n, Representative images of hearts. Original images in Supplementary Fig. 1. Three independent experiments performed. o, Heart weights normalized to body weight. p, Values of infected mice from o normalized to average of uninfected values from o. For o,p, n shows biologically independent weight-matched animals from two out of three independent experiments. Mean ± s.e.m. Two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s (c,d) or Tukey test (g–m). One-way ANOVA with Tukey test (o). Two-tailed unpaired t-test (p). Number of biologically independent mice shown in each panel. Scale bars, 50 μm (e); 3 mm (n).

Body composition parameters before the infection were not useful for predicting the infection trajectories of LD50-challenged animals (Extended Data Fig. 1s–y). However, those that succumbed to the LD50-challenge in both age groups developed quantifiable clinical signs of disease during infection, including hypothermia and morbidity, that were predictive of fate (Extended Data Figs. 1z–dd and 2a–f). Housing mice at thermal neutrality did not protect mice in either age group (Extended Data Fig. 2g–r). We calculated health scores of individual animals over the course of the infection to generate infection trajectories. We found a bifurcation in the trajectories of young mice that was apparent by 6 h postinfection, whereas the bifurcation in the aged mice was apparent by roughly 10 h postinfection (Fig. 1c,d and Extended Data Fig. 2c,f). The survivors in each age group did not differ in their ability to control the infection levels, nor did we detect differences in pathogen burdens between those that succumb to the LD50 (Extended Data Fig. 3a–o). Thus, infection outcomes in both age groups are driven by differences in the ability of the host to adapt to the infection, rather than differences in resistance mechanisms1,2,7. Taken together, our data show that the infectious inoculum is equivalent across age groups, and there are no apparent age-related differences in resistance mechanisms needed to control pathogen levels. instead, differences in survival reflect variation in cooperative defences. Thus, our LD50 polymicrobial sepsis model is an ideal system to investigate how ageing affects disease tolerance and the potential role of antagonistic pleiotropy.

Age shapes sepsis disease trajectories

Sepsis is defined as a life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection14. Despite receiving the same inoculum challenge and showing comparable pathogen burdens (Extended Data Fig. 3a–o), the differences in physiologies before infection (Extended Data Fig. 1a–q) caused young and aged dying mice to have distinct responses that yielded different disease trajectories. Although dying mice of both age groups showed hypothermia and morbidity of comparable severity (Extended Data Figs. 1z–dd and 2a–f), the kinetics of disease and death were delayed in aged mice (Fig. 1a–d and Extended Data Figs. 2a–f and 4a). Young dying mice showed severe congestion in all organs analysed including the liver, spleen, kidney, lung and heart demonstrating impaired circulatory integrity (Fig. 1e,f and Extended Data Fig. 4b–f). Aged mice showed congestion in the liver, spleen and kidney, albeit congestion severity was less than what we observed in these same organs from young mice (Fig. 1e,f and Extended Data Fig. 4b–f). Compared with age-matched uninfected and surviving mice, dying mice from both age groups also showed significantly higher amounts of the renal damage marker blood urea nitrogen (BUN); however, concentrations were higher in aged mice compared with young dying mice (Fig. 1g). Consistent with this, aged dying mice had elevated amounts of circulating creatinine compared with young dying mice (Fig. 1h). Both young and aged dying mice showed comparable decline in the concentrations of albumin and comparable elevated concentrations of liver damage markers including alanine aminotransaminase (ALT) and aspartate transaminase (AST) (Fig. 1i,j and Extended Data Fig. 4g). Young but not aged dying, mice showed elevated amounts of troponin I, a marker of cardiac damage (Fig. 1k). Dying mice of both age groups showed elevated amounts of B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP), which is released on ventricular wall stretch and is a biomarker for heart failure15,16, although concentrations were significantly higher in the young dying mice compared with the aged dying mice (Fig. 1l). Galectin-3, which is implicated in cardiac fibrosis and remodelling and is clinically used as a biomarker for myocardial injury and the diagnosis and prognostication of heart failure17, was also slightly elevated at comparable amounts in dying mice of both age groups (Fig. 1m).

Our gross examination of organs and histopathology analyses, revealed further cardiac differences. Young dying mice showed enlarged hearts with changes in geometric shape, and histological evidence of oedema, changes in cardiomyocyte appearance and hypereosinophilia with increased cardiomyocyte score and leukocyte infiltration (Fig. 1e,n–p, Extended Data Fig. 4h–j and Supplementary Fig. 1). Aged dying mice showed severe cardiac atrophy with changes in geometric shape (Fig. 1n–p, Extended Data Fig. 4h–j and Supplementary Fig. 1). The rapid kinetics of cardiac remodelling we observed in our mouse models is comparable to what has been reported in humans18,19. Histopathological analysis revealed that hearts from aged dying mice showed similar, although less pronounced, histological changes in cardiomyocyte appearance and leucocyte infiltration indicating that similar acute microscopic changes are associated with different cardiac remodelling at the macroscopic level in young and aged dying septic hosts, perhaps consistent with a limited spectrum of histologic changes in the acute time frame of the disease (Fig. 1e and Extended Data Fig. 4h–j). RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis revealed distinct molecular signatures indicative of cardiac remodelling (Extended Data Fig. 4k–t). Young dying mice had enrichment of genes involved in apoptosis, negative regulation of protein catabolic process, response to muscle stretch, regulation of cell shape and cardiac muscle tissue morphogenesis, which is consistent with cardiac remodelling and cardiomegaly (Extended Data Fig. 4n–t). The cardiac transcriptome of aged dying mice had enrichment of genes involved in ubiquitination, autophagic cell death, negative regulation of cell growth, cardiac muscle development and cell proliferation, which is consistent with their cardiac atrophic remodelling phenotype (Extended Data Fig. 4n–t). Gene ontology analysis also revealed that aged and young dying mice had distinct gene depletion profiles (Extended Data Fig. 4n–t). Taken together, our data demonstrate that genetically identical mice at different life stages, though infected with the same pathogen and dose, and showing comparable pathogen burdens, experience distinct disease trajectories leading to death. These divergent courses are marked by opposing patterns of cardiac remodelling, differences in cardiac injury and ventricular stretch (possibly suggestive of cardiac failure), evidence of differential renal damage as well as differences in sickness and death kinetics.

Age-specific sepsis survival paths

The distinct routes to death suggested that what is important for survival of the LD50 would be different for aged and young mice. LD50-challenged young survivors were able to maintain their body temperature and did not show clinical signs of disease over the course of the infection, which is indicative of an endurance phenotype1 (Fig. 1c and Extended Data Figs. 1z–dd and 2a–c). By contrast, aged LD50-challenged survivors showed a resilience health trajectory1, with a sickness phase characterized by morbidity and hypothermia that plateaued at roughly 6–8 h postinfection, and a return to baseline health between 24 h and 48 h postinfection (Fig. 1d and Extended Data Figs. 1z–dd and 2d–f). These differences in health trajectories were independent of pathogen burdens (Extended Data Fig. 3a–o), indicating that the presence of a sickness phase in aged survivors was not due to impaired resistance defences.

Aged surviving mice were protected from both kidney and liver damage, whereas young survivors were protected from kidney damage, but showed elevated amounts of AST and a trend towards elevated ALT suggesting they experienced liver damage (Fig. 1g–j). Young survivors were protected from cardiomegaly, oedema and leucocyte infiltration, and instead showed a trend towards mild cardiac atrophy compared with uninfected young mice (Fig. 1n–p, Extended Data Fig. 4h–j and Supplementary Fig. 1). Aged survivors showed cardiomegaly with histological changes in cardiomyocyte appearance, and without histological changes in oedema or a significant increase in leucocyte infiltration (Fig. 1n–p, Extended Data Fig. 4h–j and Supplementary Fig. 1). RNA-seq analysis revealed the cardiac transcriptomes of the aged and young survivors of the LD50 were distinct. Furthermore, they were different from age-matched LD50-infected dying and uninfected control mice (Extended Data Fig. 4k–m). Gene ontology analysis showed that young survivors had an enrichment of genes involved in the unfolded protein response, amino acid transport, retinoid and/or retinol process and sodium ion processes (Extended Data Fig. 4n,o). By contrast, the aged survivors of the LD50 had enrichment of genes involved in the regulation of collagen fibril organization and biosynthetic processes, wound healing, cellular response to amino acid and response to endoplasmic reticulum stress (Extended Data Fig. 4p). Finally, both aged and young survivors were protected from cardiac damage (Fig. 1k–m). Thus, despite identical pathogen exposure, surviving animals follow distinct, age-dependent survival trajectories.

Foxo1 supports tolerance in young hosts

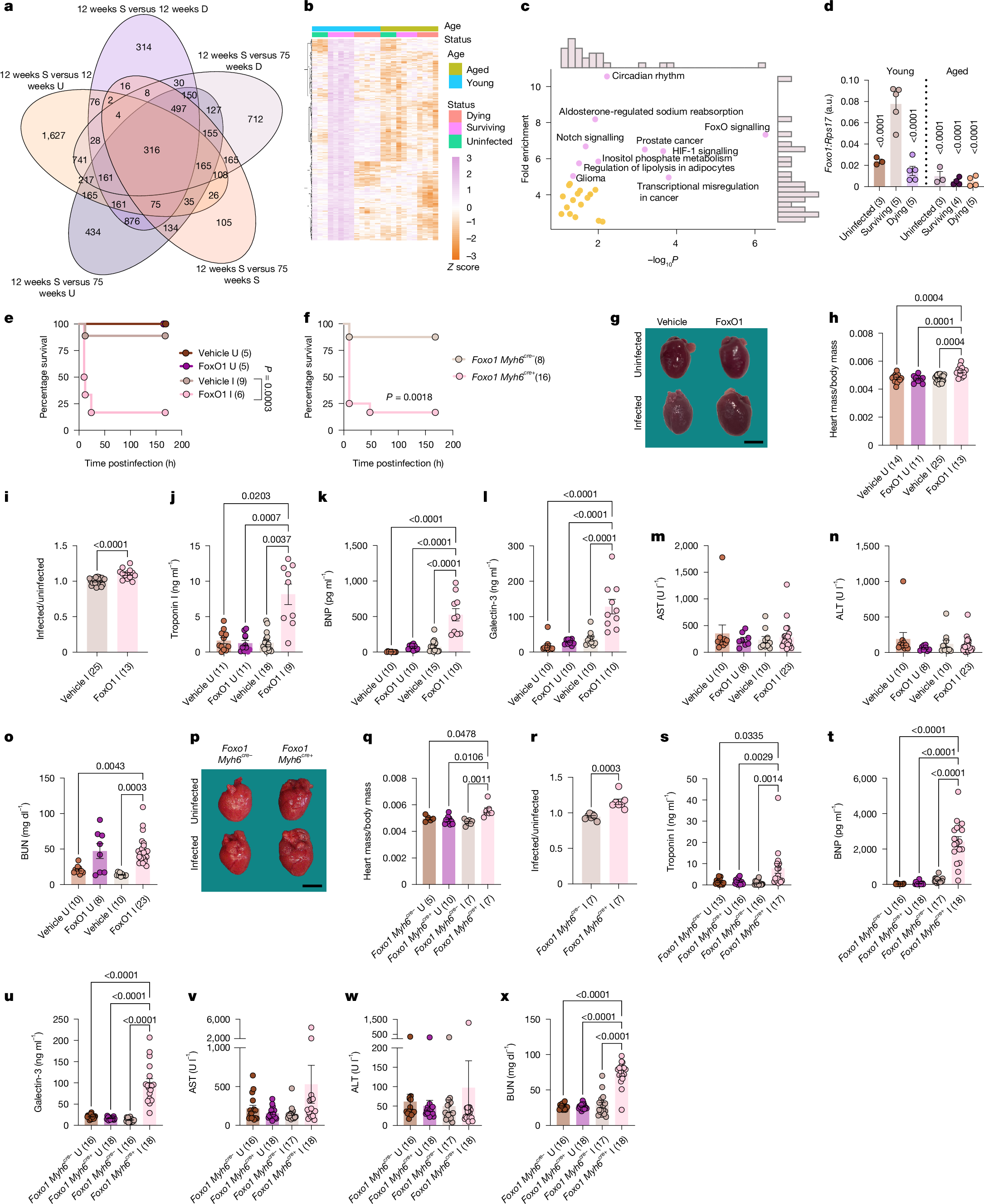

From our RNA-seq analysis of the heart, we revealed 316 genes that were significantly upregulated in the young LD50-challenged survivor hearts compared with the other 5 animal groups (Fig. 2a,b). Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis of this expression signature showed the enrichment of various metabolic, cell cycle or survival, muscle and hormone signalling processes, with FoxO signalling pathways being the most significantly enriched pathway (Fig. 2c). Whereas cardiac Foxo1 expression and protein concentrations were not different between aged and young animals under uninfected fed and fasted conditions (Supplementary Fig. 1 and Extended Data Fig. 5a–g), we found cardiac Foxo1 was differentially regulated in aged and young hosts when challenged with sepsis and in a fate specific manner. Cardiac Foxo1 expression was significantly higher in young LD50-challenged survivors compared with young uninfected and LD50-challenged dying mice, as well as aged uninfected, dying and surviving mice (Fig. 2d and Extended Data Fig. 5h). Protein concentrations of FoxO1 were also elevated without an increase in the amounts of Thr24 or Ser256 phosphorylation (phosphorylated FoxO1, inactive; unphosphorylated FoxO1, active), indicating there was increased cardiac FoxO1 activity in young surviving mice compared with all other conditions (Supplementary Fig. 1 and Extended Data Fig. 5i–t). Examination of other organs revealed the association between Foxo1 induction and survival in young mice to be specific to the heart (Extended Data Fig. 5h). In aged mice, survival of sepsis did not correlate with increased expression or activation of FoxO1 in the heart or any other organ examined (Fig. 2d, Extended Data Fig. 5h–t and Supplementary Fig. 1).

a, Venn diagram of cardiac genes induced in young survivors. b,c, Heat map (b) and top ten enriched KEGG pathways (c) of overlapping genes across all five comparisons in a. One experiment was performed. d, Cardiac Foxo1 expression (10 h young, 24 h aged). Data also in Extended Data Fig. 5h. n shows biologically independent animals from one out of two independent experiments. e, Young mice ±FoxO1 inhibitor and ±infection survival. f, Young infected Foxo1 Myh6cre− and Foxo1 Myh6cre+ littermate survival. n shows biologically independent animals from two out of two independent experiments. g, Representative heart images at 10 h postinfection. Original images in Supplementary Fig. 1. Four independent experiments performed. h, Heart/body weight ratios at 10 h postinfection. i, Infected mice from h normalized to average uninfected. n shows biologically independent weight-matched animals from four out of four independent experiments (h,i). j, Troponin I. k, BNP. l, Galectin-3. m, AST. n, ALT. o, BUN in young mice ±FoxO1 inhibitor and ±infection at 10 h postinfection. n shows biologically independent animals from two out of two (k,l) or three out of three (j,m–o) independent experiments. p, Representative heart images at 10 h postinfection. Original images in Supplementary Fig. 1. Four independent experiments performed. q, Heart/body weight ratios at 10 h postinfection. r, Infected values from q normalized to average uninfected. n shows biologically independent weight-matched animals from four out of four independent experiments (q,r). s, Troponin I. t, BNP. u, Galectin-3. v, AST. w, ALT. x, BUN in Foxo1 Myh6cre− and Foxo1 Myh6cre+ littermates ±infection at 10 h postinfection. n shows biologically independent animals from four out of four independent experiments. Mean ± s.e.m. Two-way ANOVA with Tukey test (d,h,j–n,o,q,s–w), log-rank analysis (e,f), two-tailed unpaired t-test (i,r). Number of biologically independent mice shown in panels. Scale bars, 3 mm (g,p). a.u., arbitrary units; D, dying; I, infected;