Human and bacterial genetic variation shape oral microbiomes and health

TL;DR

Human genetic variants at 11 loci, including FUT2 and AMY1, shape oral microbiome composition and associate with dental health risks like dentures use, revealing host-microbial interactions influencing oral health.

Key Takeaways

- •Human genetic variation at 11 loci influences oral microbiome composition, with FUT2 and AMY1 showing strong associations.

- •Genetic variants in genes like FUT2, AMY1, and PITX1 link to dentures use, suggesting impacts on oral health through microbiome modulation.

- •Oral microbiome diversity changes with age, increasing in early childhood and declining later, but is not strongly affected by ASD or sex.

Tags

Abstract

Human genetic variation influences all aspects of our biology, including the oral cavity1,2,3, through which nutrients and microbes enter the body. Yet it is largely unknown which human genetic variants shape a person’s oral microbiome and potentially promote its dysbiosis3,4,5. We characterized the oral microbiomes of 12,519 people by re-analysing whole-genome sequencing reads from previously sequenced saliva-derived DNA. Human genetic variation at 11 loci (10 new) associated with variation in oral microbiome composition. Several of these related to carbohydrate availability; the strongest association (P = 3.0 × 10−188) involved the common FUT2 W154X loss-of-function variant, which associated with the abundances of 58 bacterial species. Human host genetics also seemed to powerfully shape genetic variation in oral bacterial species: these 11 host genetic variants also associated with variation of gene dosages in 68 regions of bacterial genomes. Common, multi-allelic copy number variation of AMY1, which encodes salivary amylase, associated with oral microbiome composition (P = 1.5 × 10−53) and with dentures use in UK Biobank (P = 5.9 × 10−35, n = 418,039) but not with body mass index (P = 0.85), suggesting that salivary amylase abundance impacts health by influencing the oral microbiome. Two other microbiome composition-associated loci, FUT2 and PITX1, also significantly associated with dentures risk, collectively nominating numerous host–microbial interactions that contribute to tooth decay.

Similar content being viewed by others

Metagenome-genome-wide association studies reveal human genetic impact on the oral microbiome

Genome-wide association study identifies host genetic variants influencing oral microbiota diversity and metabolic health

Impact of high altitude on composition and functional profiling of oral microbiome in Indian male population

Main

When Antonie van Leeuwenhoek first observed bacteria as ‘animalcules’ in scrapings from his teeth in the seventeenth century, one of his first inquiries involved the extent of their variation among people6. Oral microbiomes are now known to vary abundantly across people7,8,9, and twin studies have shown that some of this variation is heritable1,2,3. However, few human genetic polymorphisms have been associated with the abundances of specific oral microbial species3,4,5; study sizes so far (n < 3,000) have provided limited power to detect robust genetic effects. Larger genome-wide association studies (GWAS) of the gut microbiome (n = 5,959–18,340) have consistently replicated two effects of variation at the LCT and ABO loci on gut microbial abundances10,11,12,13, and larger GWAS of oral microbiomes might yield similar discovery.

Oral pathologies, such as dental caries, result from dysbiosis of the oral microbiome14. Untreated pathologies can progress to oral infections which carried high mortality rates before modern dentistry and antibiotics15. Susceptibility to caries and other oral pathologies is also strongly influenced by genetics16,17, and GWAS have identified 47 loci harbouring such genetic effects18. However, whether these or other genetic effects act by modulating the composition of the oral microbiome is at present unknown. Identifying such interactions could point to microbial drivers of cariogenesis9.

Given the effects of human hosts and resident microbes on each other’s survival and evolutionary trajectory, the human microbiome is an example of symbiosis19,20. The stability of the gut microbiome in individuals21, its codiversification with humans22 and abundant structural variation of its microbial genomes23 all suggest intricate genetic interactions between microbiomes and their human hosts, whereby microbial genomes adapt to genetic variation across people. A recently observed example of such an interaction with the gut microbiome is a structural variant in the Faecalibacterium prausnitzii genome that includes genes encoding an N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc)-metabolizing pathway and interacts with human ABO variation24. Whether such specific co-adaptation commonly occurs in oral microbiomes remains an open question.

Oral microbiome profiles of 12,519 people

To create a dataset suitable for exploring variation in the oral microbiome and the way it is shaped by human genetic variation, we analysed DNA sequencing reads previously generated from whole-genome sequencing (WGS) of saliva samples from 12,519 participants in the Simons Foundation Powering Autism Research (SPARK) cohort25 (Fig. 1a), building on previous work26,27. WGS captured substantial non-human genomic information28, with a median of 8.4% ([4.6%,14.7%], quartiles) of sequencing reads not mapping to the human reference genome (Extended Data Fig. 1a). Many of these unmapped reads instead mapped to clade-specific marker genes in microbial genomes29, enabling quantification of relative microbial abundances. This produced the largest collection of oral microbiome profiles (n = 12,519) generated so far, measuring the abundances of 645 microbial species present at >1% frequency, including 439 species (spanning 13 phyla, including one fungal commensal, Malassezia restricta) commonly observed in SPARK (≥10% of participants) (Fig. 1b, Extended Data Fig. 1b and Supplementary Table 1). Comparing these profiles across individuals showed that age was a major driver of interindividual variation in oral microbiome composition, unlike autism spectrum disorder (ASD) case status, sex and genetic ancestry (Fig. 1c and Extended Data Fig. 1c–g). Across the lifespan represented in SPARK (age 0–90 years), mean species diversity sharply increased in the first few years of life (representing when the oral cavity is colonized, diet diversifies and primary teeth are acquired) and then decreased slowly with age8 (Fig. 1d). Individual species exhibited vastly different abundance trajectories over the lifespan, with some observed predominantly in adults and others predominantly in children (Extended Data Fig. 1h–k).

a, Generation of paired datasets of human genetic variation and oral microbiome composition from WGS of saliva samples from the SPARK cohort (n = 12,519). Human genetic variants were previously called with DeepVariant and relative abundances of microbial species were estimated with MetaPhlAn 4 (ref. 29) from sequencing reads that did not map to the human genome. b, Phylogenetic tree based on genomic divergence among 439 microbial species observed in ≥10% of SPARK participants. Phyla are indicated by dot colour and genera with more than five species are indicated with labelled grey sectors. c, Contributions of age, sex, ASD case status and genetic ancestry principal components (PC1 through PC5) to variation in oral microbial species abundances. For each factor, the fraction of variance in species abundance explained by the factor was computed for each of the 439 species, and the box and whisker plot shows the distribution of this quantity across the 439 species. ASD status explained a median fraction of variance of 0.002. Boxes span quartiles; centres indicate medians and whiskers are drawn up to 1.5× the interquartile range. d, Species diversity in the oral microbiome as a function of host age. The red line indicates median Shannon entropy and the shaded region indicates the interquartile range. Oral microbial diversity increases substantially over the first few years of life, plateaus and then modestly declines in late adulthood. Images in a were reproduced from Pixabay (https://pixabay.com) under a CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Licence.

Human genetics shapes oral microbiome composition

To identify human genetic variants that influence interindividual differences in the abundances of microbial taxa, we first tested the abundances of taxa detectable in ≥10% of participants for association with common human genetic variants, accounting for family structure using a linear mixed model30,31. Human genetic variants at seven loci associated with the abundance of at least one taxon at study-wide significance (P < 4.0 × 10−11; Extended Data Fig. 2a), with only one locus (SLC2A9) previously identified4. As several loci associated with the abundances of many species (Supplementary Tables 2 and 3) and none associated with α-diversity (Extended Data Fig. 2b), we developed a statistical test to capture pleiotropic effects on many species in an interdependent microbial community32,33,34, using principal component analysis (PCA) to enable efficient genome-wide association testing (Fig. 2a and Methods). Similar to a recent approach for GWAS on high-dimensional cell state phenotypes in single-cell RNA-seq data35, this approach also reduces multiple-testing burden by testing each genetic variant only once.

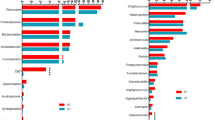

a, Converting relative abundances of M microbial species (left) into M orthogonal PCs (middle) allows combining chi-squared statistics for a given genetic variant (one per PC) into a single chi-squared test statistic with M degrees of freedom (right). b, Genome-wide associations with oral microbiome composition in SPARK (top, n = 12,519) and dentures use in UKB (bottom, n = 418,039). Nonsense (red squares), missense (green triangles) and multi-allelic copy number variants (CNVs) (blue diamonds) are highlighted. c, Associations of variants at the FUT2 locus with relative species abundance for the five microbial species with the strongest associations (left five plots); colour indicates effect direction (plots with red points correspond to species which are more abundant in people with functional FUT2 (that is, secretors); blue, less abundant) and colour saturation indicates linkage disequilibrium with rs601338 (FUT2 W154X). Association strengths from the combined test for association with oral microbiome composition show much greater statistical power (rightmost plot). d, Effect sizes (in s.d. units) on relative abundance of microbial species for individuals heterozygous for functional FUT2 (light-filled circles) and for homozygotes (dark-filled circles) relative to those with no functional FUT2 (empty circles). For each effect direction, the ten most significantly associated species are shown. P values are from a recessive model of FUT2 W154X genotype. Error bars, 95% CIs. e, Microbial taxa whose abundance associated with FUT2 genotype (FDR < 0.1) shown on the phylogenetic tree of 439 species (red, taxa whose relative abundances increased with functional FUT2; blue, decreased). Two significantly associated phyla (Firmicutes and Actinobacteria; P = 1.2 × 10−4 and 4.0 × 10−5, respectively) are highlighted with yellow sectors. At the species level (outermost circle), dot sizes increase with statistical significance. P values were computed using one-sided chi-squared test (top half, b), two-sided linear regression (bottom half, b) or two-sided linear mixed models (c,d).

Applying this approach to SPARK identified four additional human genomic loci (11 total) at which common genetic variation associated with oral microbiome composition (P < 5 × 10−8; Fig. 2b and Extended Data Table 1). The principal component (PC)-based test was well-calibrated (Extended Data Fig. 2c) and top signals were confirmed by multivariate distance matrix regression33,36 (Extended Data Fig. 2d,e). The association signals tended to distribute across many microbial PCs (mPCs; Extended Data Fig. 2f–p), suggesting that human genetic variants subtly influence many axes of microbial community coordination. Among the ten new loci, eight implicated genes—and in several cases, specific variants—with readily interpretable functions that could explain their associations with microbiome composition.

-

Three loci contained genes encoding highly expressed salivary proteins: salivary amylase (encoded by AMY1; P = 1.5 × 10−53, top association), submaxillary gland androgen-regulated proteins (SMR3A and SMR3B; P = 1.4 × 10−12) and basic salivary proline-rich proteins (PRB1–PRB4; P = 1.1 × 10−11). These associations seemed to be driven mainly by genetic variants that modify gene expression or copy number (Extended Data Table 1, Extended Data Fig. 3 and Supplementary Note 1). Consistent with these results, heritability-partitioning analysis37 indicated that genetic effects on oral microbiome composition are enriched at genes specifically expressed in salivary glands (P = 0.02, Extended Data Fig. 4a).

-

Two loci contained genes with established roles in immune function: the HLA class II genes, which encode proteins that present peptides in adaptive immunity, and TLR1, encoding Toll-like receptor 1, that binds bacterial lipoproteins in innate immunity. The strongest association at TLR1 involved a missense variant (rs5743618; P = 6.2 × 10−18) that produces the I602S substitution known to inhibit trafficking of TLR1 to the cell surface, reducing immune response in a recessive manner38,39. Consistent with these reports, I602S associated recessively with microbial abundances (P = 6.7 × 10−29; Extended Data Fig. 4b).

-

Two other loci, ABO and FUT2, encode glycosyltransferases that together determine expression of histo-blood group antigens on epithelial cells and secreted proteins (in addition to the well-known role of ABO in determining blood type). This broader role is important to microbial species that interact with mucosal surfaces, such that both loci are known to influence the gut microbiome10,11,12,13,