Language model-guided anticipation and discovery of mammalian metabolites

TL;DR

DeepMet, a chemical language model trained on known metabolite structures, predicts and prioritizes previously unrecognized mammalian metabolites. It integrates with mass spectrometry data to facilitate discovery, successfully identifying dozens of novel metabolites and demonstrating the potential of language models to map the metabolome.

Key Takeaways

- •DeepMet uses chemical language models to anticipate unknown metabolites by learning from known structures, enabling systematic exploration of metabolic 'dark matter'.

- •The model generates metabolite-like structures that overlap with known metabolites and recapitulate enzymatic transformations, prioritizing candidates based on sampling frequency.

- •Integration with mass spectrometry data allows DeepMet to prioritize plausible chemical structures for unidentified peaks, improving metabolite identification and discovery.

- •DeepMet successfully predicted many metabolites later added to databases, highlighting its ability to fill gaps in metabolic knowledge and guide experimental validation.

Tags

Abstract

Despite decades of study, large parts of the mammalian metabolome remain unexplored1. Mass spectrometry-based metabolomics routinely detects thousands of small molecule-associated peaks in human tissues and biofluids, but typically only a small fraction of these can be identified, and structure elucidation of novel metabolites remains challenging2,3,4. Biochemical language models have transformed the interpretation of DNA, RNA and protein sequences, but have not yet had a comparable impact on understanding small molecule metabolism. Here we present an approach that leverages chemical language models5,6,7 to anticipate the existence of previously uncharacterized metabolites. We introduce DeepMet, a chemical language model that learns from the structures of known metabolites to anticipate the existence of previously unrecognized metabolites. Integration of DeepMet with mass spectrometry-based metabolomics data facilitates metabolite discovery. We harness DeepMet to reveal several dozen structurally diverse mammalian metabolites. Our work demonstrates the potential for language models to advance the mapping of the mammalian metabolome.

Main

Mass spectrometry-based metabolomics typically detects thousands of distinct chemical entities in any given biological sample8, but even in human tissues or biofluids, the majority of these are not routinely linked to a chemical structure2,3. This profusion of unidentified chemical entities has been dubbed the chemical ‘dark matter’ of the metabolome4. The existence of this metabolic dark matter suggests that existing metabolic maps are far from complete9,10,11,12. New approaches are needed to illuminate the dark matter of the metabolome in a systematic manner.

Generative models based on deep neural networks have emerged as a powerful approach to study the structure and function of biological macromolecules13. Language models trained on protein sequences are capable of learning the latent evolutionary forces that have shaped extant sequences in order to design new proteins with desired functions, predict the effects of unseen variants, and even forecast protein sequences that are likely to evolve in the future14,15,16,17. Language models can also be trained on the chemical structures of small molecules by leveraging formats that represent these structures as short strings of text, a concept that has been exploited by a large body of work over the past decade5,6,7. So far, however, this paradigm has primarily been applied to explore synthetic chemical space in the setting of drug discovery. Here we introduce DeepMet, a chemical language model trained on the structures of known metabolites that anticipates the existence of previously unrecognized metabolites (Fig. 1a). We develop approaches to integrate DeepMet with mass spectrometry-based metabolomics data that enable de novo identification of metabolites in complex tissues and harness these approaches to reveal several dozen previously unrecognized metabolites.

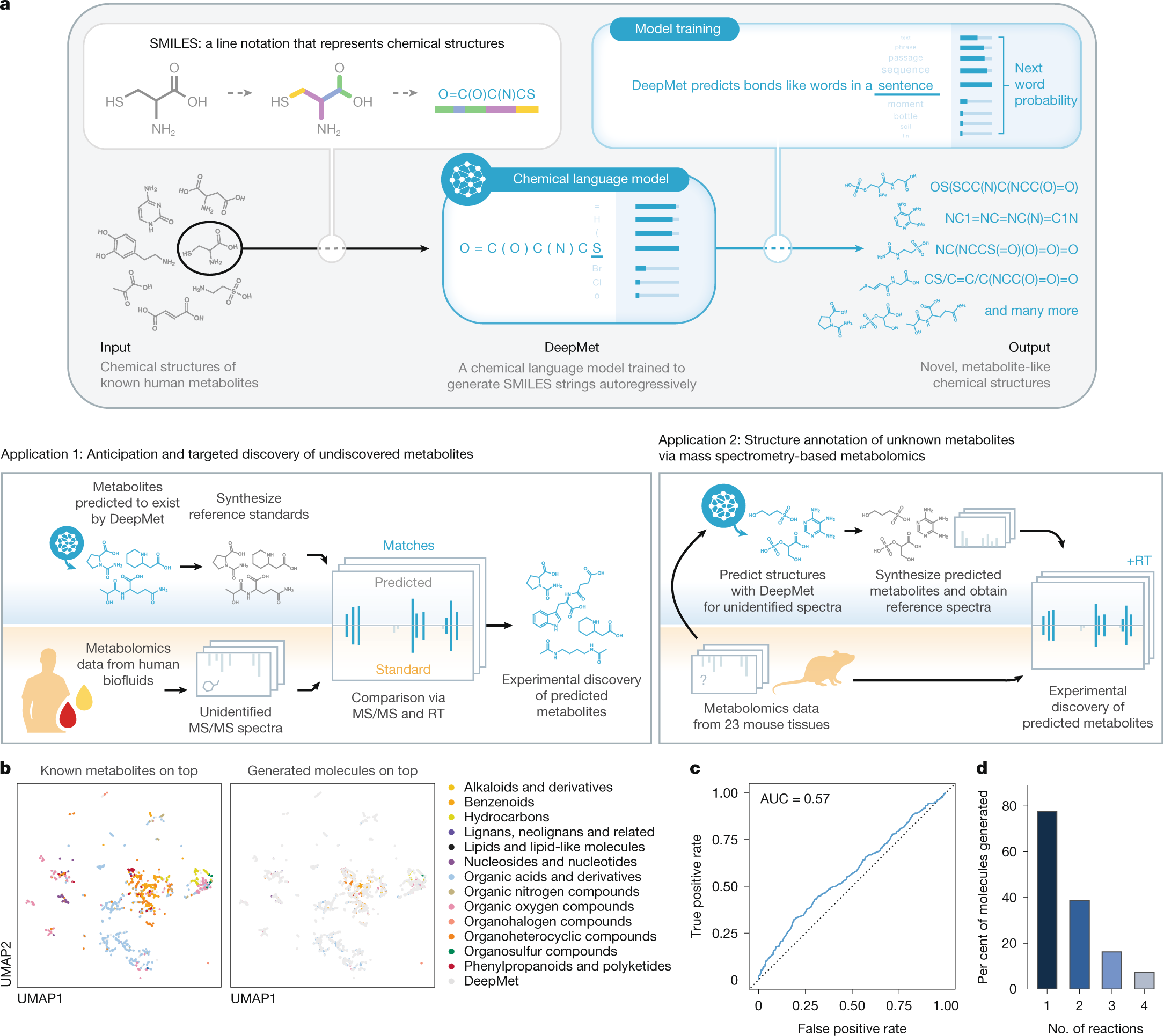

a, Schematic overview of DeepMet. RT, retention time. b, UMAP visualization of the chemical space occupied by known metabolites and generated molecules. Left, known metabolites superimposed over generated molecules. Right, generated molecules superimposed over known metabolites. Known metabolites are coloured by their assigned superclasses in the ClassyFire chemical ontology. c, Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of a random forest classifier trained to distinguish between known metabolites and generated molecules in cross-validation. d, Proportion of enzymatic biotransformations of known metabolites23 recapitulated by DeepMet, shown as a function of the number of rule-based transformations applied sequentially to the original metabolite.

Learning the language of metabolism

Metabolites are synthesized from a small pool of precursors such as amino acids, organic acids, sugars and acetyl-CoA via a limited repertoire of enzymatic transformations. These shared biosynthetic origins result in the overrepresentation of certain physicochemical properties and substructures among metabolites, compared with synthetic compounds made in the laboratory18,19,20. We hypothesized that a chemical language model could learn from the structural features of known metabolites to access previously unrecognized structures from metabolite-like chemical space.

To test this hypothesis, we assembled a training set of 2,046 metabolites that had been experimentally detected in human tissues or biofluids21 and represented these as short strings of text in simplified molecular-input line-entry system (SMILES) notation22. We trained a long short-term memory (LSTM) language model on this dataset of known metabolite structures after first pretraining it on drug-like structures from the ChEMBL database, and used the trained model to generate 500,000 SMILES strings in order to evaluate its understanding of metabolism.

Several lines of evidence indicated that our language model was able to appreciate the structural features of known metabolites and exploit this understanding to generate metabolite-like structures. First, we visualized the chemical space occupied by generated molecules and known metabolites using the nonlinear dimensionality reduction algorithm uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP). Generated molecules overlapped extensively with known metabolites (Fig. 1b). Second, we trained a random forest classifier to distinguish the generated molecules from a set of known human metabolites that had been deliberately withheld from the language model during training. We found that this classifier could not accurately separate the two classes of molecules, and instead performed only marginally better than random guessing (Fig. 1c and Extended Data Fig. 1a–c). Third, because many biosynthetic enzymes are known to be promiscuous in the substrates that they accept, we tested whether the generated molecules could be rationalized as enzymatic transformations of known metabolites. We found that the language model recapitulated 77.5% of one-step enzymatic transformations of known metabolites predicted by the rule-based platform BioTransformer23 (Fig. 1d and Extended Data Fig. 1d,e), despite not having been provided any explicit information about enzymatic reactions during training. Our model, however, predicted a much broader spectrum of structures than the rule-based approach, with the vast majority of structures generated by the language model not being predicted by BioTransformer (Extended Data Fig. 1f). Fourth, we found that the generated molecules were more structurally similar to known metabolites than molecules with identical molecular formulas sampled at random from PubChem or ChEMBL (Extended Data Fig. 1g–i).

These results introduce a language model of metabolite-like chemical space, which we named DeepMet.

Anticipating unrecognized metabolites

In the setting of protein biochemistry, language models can be leveraged to predict the functional impacts of unseen mutations and to forecast the evolution of future proteins14,15,16,17. We hypothesized that the same principle could be applied to predict the structures of previously unrecognized metabolites. Unlike nucleotide or protein sequences, however, chemical structures do not have a unique textual representation24, and we observed that DeepMet assigned markedly different likelihoods to different SMILES strings representing the same chemical structure (Extended Data Fig. 2a–c).

In lieu of calculating the likelihoods of individual SMILES strings, we reasoned that chemical structures viewed by DeepMet as more plausible extensions of the training set would be sampled more frequently in aggregate, considering all possible representations. To test this hypothesis, we drew a sample of 1 billion SMILES strings from DeepMet, and then tabulated the frequency with which each unique chemical structure appeared in this sample (Fig. 2a). Whereas the vast majority of these structures appeared at most a handful of times in the language model output, others were generated thousands of times (Fig. 2b).

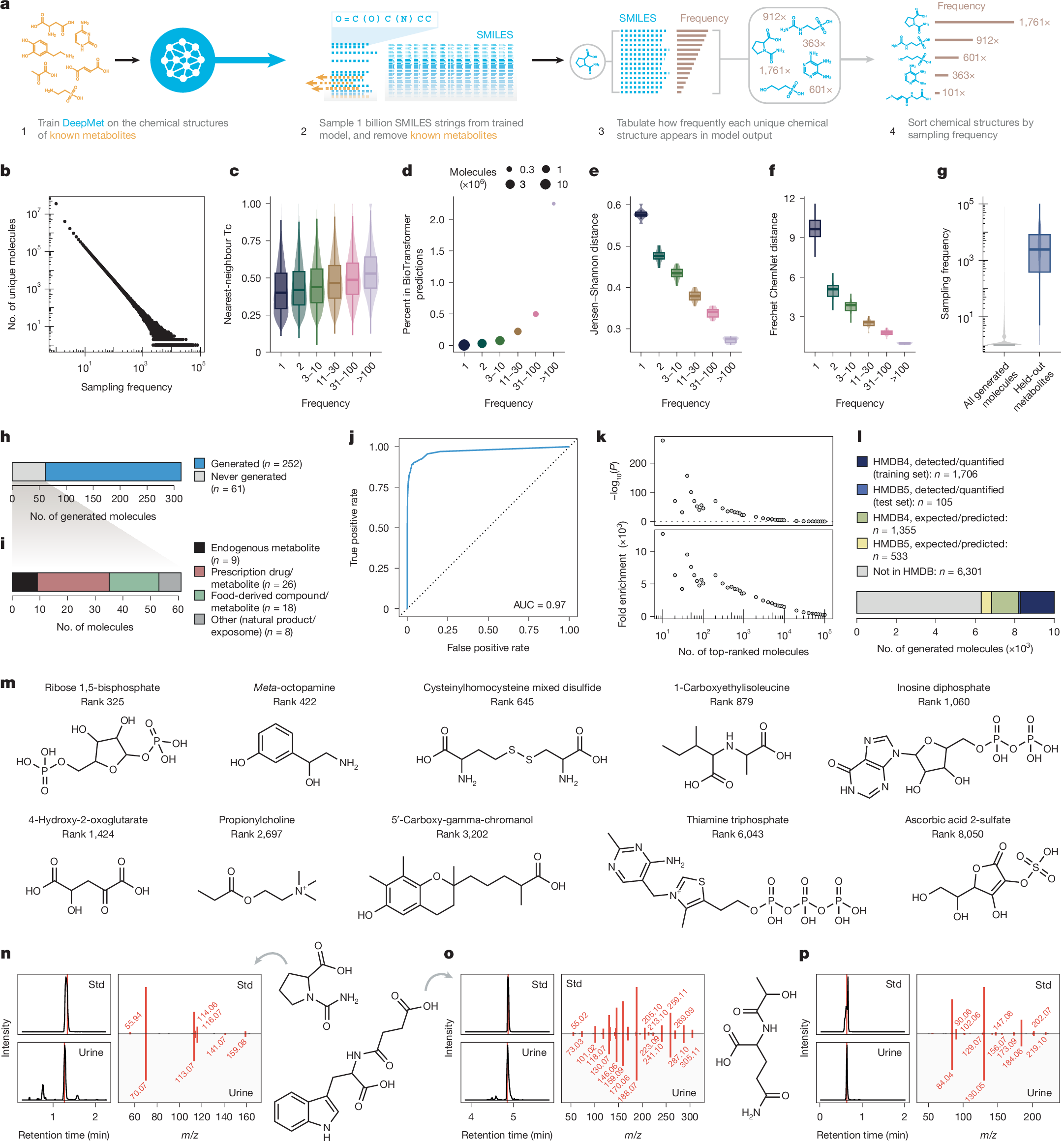

a, Schematic overview of sampling frequency calculation. b, Distribution of sampling frequencies within a sample of 1 billion SMILES strings. c–f, Properties of molecules generated with progressively increasing frequencies. c, Tanimoto coefficient (Tc) between generated molecules and their nearest neighbours in the training set (n = 50,000 randomly sampled molecules per bin). d, Proportion of generated metabolites recapitulating one-step enzymatic transformations of known metabolites predicted by BioTransformer. e, Jensen–Shannon distances between Murcko scaffolds of generated molecules and known metabolites (n = 10 folds). f, Fréchet ChemNet distances between generated molecules and known metabolites (n = 10 folds). g, Frequencies with which known metabolites withheld from the training set were sampled, compared to all generated molecules (in n = 109 sampled SMILES). h, Proportion of HMDB 5.0 metabolites generated by DeepMet. i, Categorization of the 61 HMDB 5.0 metabolites not generated by DeepMet. j, ROC curve showing prioritization of HMDB 5.0 metabolites on the basis of their sampling frequencies. k, Enrichment of HMDB 5.0 metabolites among the most frequently generated molecules (two-sided χ2 test). l, Proportion of known or predicted/expected metabolites from versions 4.0 or 5.0 of the HMDB within the top-10,000 molecules most frequently generated by DeepMet. m, Examples of metabolites annotated as predicted or expected that are actually well-studied human metabolites, and were generated with frequencies comparable to experimentally detected metabolites despite being withheld from the training set. n–p, Examples of previously unrecognized human metabolites identified in human urine (chemical structures, extracted ion chromatograms (EICs) from chemical standards (Std) and representative urine metabolomes, and mirror plots comparing MS/MS from standards versus experimental spectra). Vertical red lines show times of MS/MS acquisitions. n, N-carbamyl-proline. o, N-succinyl-tryptophan. p, N-lactoyl-glutamine.

We sought to characterize these frequently generated molecules. Molecules sampled more frequently by DeepMet exhibited a higher degree of structural similarity to known metabolites (Fig. 2c and Extended Data Fig. 2d); were disproportionately likely to overlap with plausible enzymatic transformations23 of known metabolites (Fig. 2d and Extended Data Fig. 2e); were more likely to share a chemical scaffold with a known metabolite (Fig. 2e); and, as quantified by the Fréchet ChemNet distance25, were predicted to have a more similar spectrum of biological activities to known metabolites (Fig. 2f). Thus, molecules generated more frequently by DeepMet were disproportionately metabolite-like.

This finding led us to more directly test whether this sampling frequency could be used to prioritize candidate metabolites for discovery. To evaluate this possibility, we withheld known metabolites from the training set in order to simulate the discovery of unknown metabolites. The withheld metabolites were generally among the most frequently generated molecules proposed by the language model (Fig. 2g), such that the sampling frequency alone separated withheld metabolites from other generated molecules with an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) of 0.98 (Extended Data Fig. 2f).

We therefore sought to prospectively evaluate the ability of DeepMet to predict future metabolite discoveries. A total of 313 metabolites had been added to version 5.0 of the Human Metabolome Database (HMDB) after our training dataset was finalized26. DeepMet successfully generated 252 of these 313 metabolites (81%; Fig. 2h), and most of the 61 structures that were not successfully generated were not products of endogenous human metabolism, but were instead derived from prescription drugs, food, the microbiome or environmental chemicals (Fig. 2i and Extended Data Fig. 2g,h). Moreover, we again found that the sampling frequency alone separated the HMDB 5.0 metabolites from other generated molecules (AUC = 0.97; Fig. 2j).

HMDB 5.0 metabolites were markedly enriched in the uppermost extremities of the sampling frequency distribution. The top-10,000 most frequently generated molecules, for instance, contained 105 of the 252 generated metabolites, an enrichment of about 1,500-fold over random expectation (Fig. 2k and Supplementary Table 1). Notably, this subset also included 1,888 metabolites annotated as predicted or expected in version 4.0 or 5.0 of the HMDB (Fig. 2l), which had been excluded from the training set. Several of the most frequently sampled predicted or expected metabolites were in fact well-studied metabolites that had been misannotated in the HMDB (Fig. 2m), underscoring the ability of our model to fill gaps in existing metabolic databases.

Among the top-10,000 most frequently sampled metabolites, 6,301 were absent from any version of the HMDB (Fig. 2l). These structures are those considered by DeepMet to represent the most plausible extensions of the known metabolome. We hypothesized that many of these structures were indeed mammalian metabolites.

To test this hypothesis, we obtained or synthesized chemical standards for 80 putative metabolites that ranked in the top-10,000 structures. Each of these standards was profiled by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS) and then compared against a large bank of urine and blood metabolomics data that had been collected by one laboratory using identical analytical methods. A total of 17 metabolites predicted by DeepMet were identified in human biofluids by the combination of retention time and tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS), although careful review of the literature revealed a subset of these to be known metabolites missing from the HMDB27,28,29,30 (Fig. 2n–p, Supplementary Fig. 1, and Supplementary Table 2).

Thus, DeepMet can fill the gaps in our understanding of metabolism by predicting the structures of previously unrecognized metabolites.

Prioritizing structures from accurate masses

These experiments introduce a structure-centric approach to metabolite discovery, whereby hypothetical metabolites are prioritized by a chemical language model for synthesis and targeted discovery. We also envisioned, however, that DeepMet could support more conventional approaches to metabolite discovery, whereby metabolites are targeted for structure elucidation on the basis of mass spectrometric data.

We began by asking whether DeepMet could prioritize plausible chemical structures for an unidentified metabolite given a single measurement as input: the metabolite’s exact mass. To test this possibility, we again simulated metabolite discovery by withholding known metabolites from the training set. For each held-out metabolite, we filtered the structures generated by DeepMet to those matching its exact mass (±10 ppm). We then tabulated the total frequency with which each of these structures was generated by DeepMet (Fig. 3a).

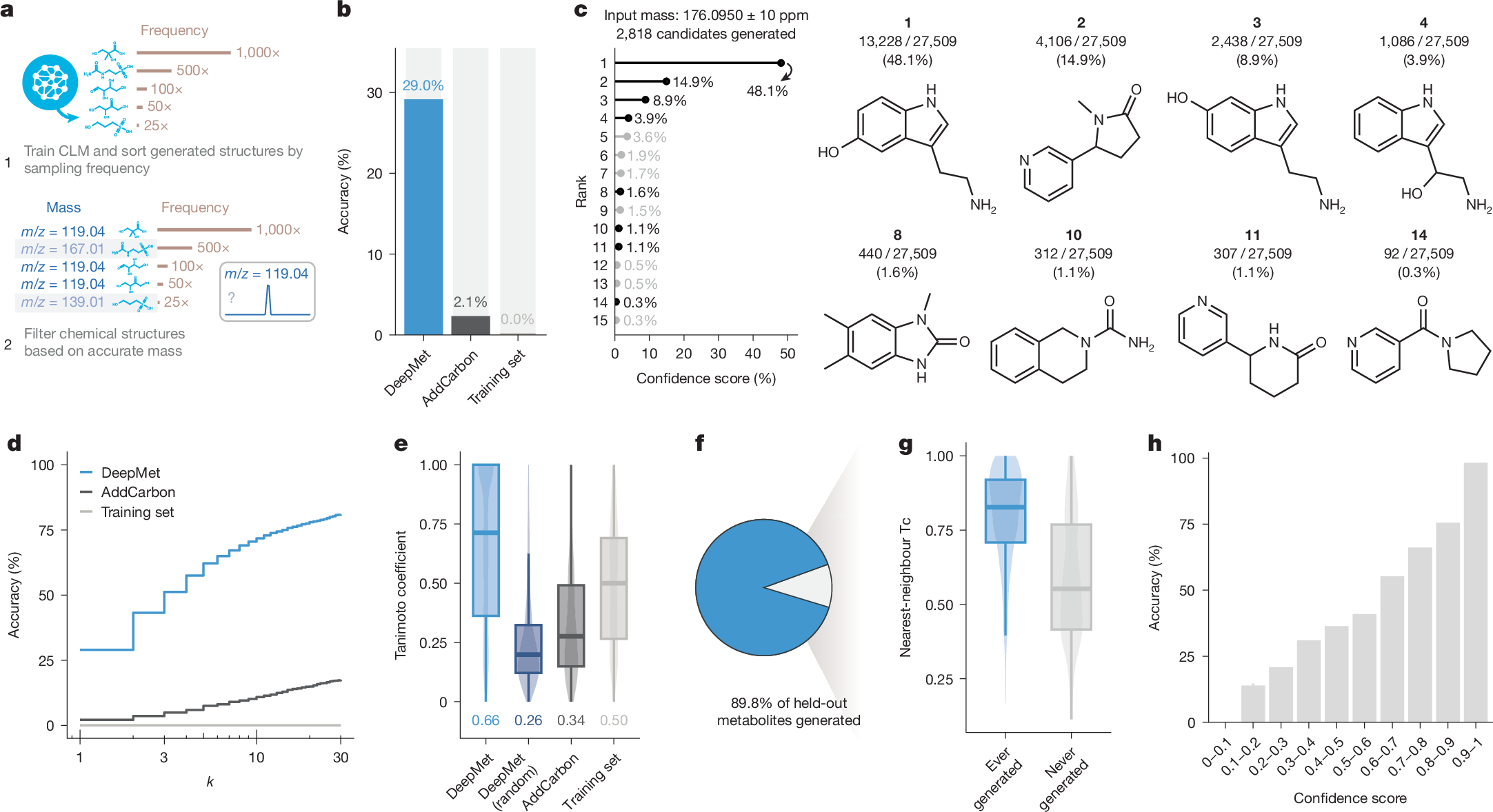

a, Schematic overview of the workflow to prioritize metabolite structures given an accurate mass measurement as input. CLM, chemical language model. b, Top-1 accuracy with which the complete chemical structures of held-out metabolites were assigned by DeepMet or two baseline approaches: AddCarbon or searching within the training set. c, Illustrative example demonstrating the use of DeepMet to prioritize candidate metabolite structures based on an accurate mass. A total of n = 27,509 sampled SMILES strings matched the input mass of 176.0950 ± 10 ppm, corresponding to n = 2,818 unique structures. Left, lollipop plot shows the sampling frequencies of the 15 most frequently generated molecules as a proportion of the 27,509 SMILES strings. Right, a subset of the generated molecules is shown, including the four most frequently generated as well as a selection of less frequently generated structures. Structures 1, 2 and 3 are known human metabolites that were not present in the training set. d, As in b, but showing the top-k accuracy curve, for k ≤ 30. e, Tanimoto coefficients between the structures of held-out metabolites and the top-ranked structures prioritized by DeepMet, random structures generated by DeepMet, or two baseline approaches. f, Proportion of held-out metabolites that were ever generated by the language model. g, Tanimoto coefficients between held-out metabolites and their nearest neighbour in the HMDB, for metabolites that were ever versus never generated by the language model. h, Proportion of correct structure assignments for held-out metabolites as a function of the DeepMet confidence score.

Across all withheld metabolites, the most frequently generated structure matched that of the held-out metabolite in 29% of cases (Fig. 3b). For instance, providing the mass of serotonin (176.0950 Da ± 10 ppm) as input yielded 27,509 SMILES strings, representing 2,818 unique chemical structures; of these, the single most frequently sampled structure was that of serotonin itself (Fig. 3c). Because serotonin had been withheld from the training set, this required DeepMet to simultaneously generate the chemical structure of an unseen metabolite, and to prioritize this structure from among thousands of chemically valid candidates.

In cases where the top-ranked structure was not that of the held-out metabolite, the correct structure was often found among a short list of candidates (Fig. 3c,d and Extended Data Fig. 3a). Moreover, when the top-ranked structure was incorrect, it was often structurally similar to the true metabolite (Fig. 3e and Extended Data Fig. 3b–j). Only 10% of held-out metabolites were never reproduced by the language model, and these metabolites tended to demonstrate a low degree of structural similarity to any other metabolite in the training set (Fig. 3f, g).

To contextualize the performance of our language model, we compared DeepMet to the AddCarbon baseline proposed by Renz et al.31 Although this simple approach has frequently outperformed more sophisticated generative models31, we nonetheless found that DeepMet markedly outperformed AddCarbon on all metrics (Fig. 3b,d,e and Extended Data Fig. 3c–e). Structures prioritized by DeepMet also demonstrated a higher degree of structural similarity to the held-out metabolites than isobaric known metabolites, reflecting the ability of the model to generalize beyond the training set into unseen chemical space.

We computed confidence scores for each structure based on the sampling frequencies of all generated molecules matching the query mass, and found that these confidence scores correlated well with the likelihood that any given structure assignment was correct (Fig. 3h and Extended Data Fig. 3k). This observation highlights a particularly useful property of DeepMet: namely, that its most confident predictions are expected to be the best candidates for experimental follow-up.

We then turned again to the 313 metabolites added in version 5.0 of the HMDB, and tested whether DeepMet would demonstrate similar performance in this prospective test set. This is a challenging task, as these metabolites are structurally distinct from those in the training set (Extended Data Fig. 3l). Nonetheless, DeepMet demonstrated comparable performance in this prospective test set (Extended Data Fig. 3m–s).

Together, these experiments establish that DeepMet can simultaneously generate and prioritize candidate structures for unidentified peaks detected by mass spectrometry.