Genetic switch between unicellularity and multicellularity in marine yeasts

TL;DR

Researchers identify genetic switches controlling facultative clonal multicellularity in marine yeasts, revealing how nutrient-responsive mechanisms and co-opted conidiation regulators enable transitions between unicellular and multicellular states.

Key Takeaways

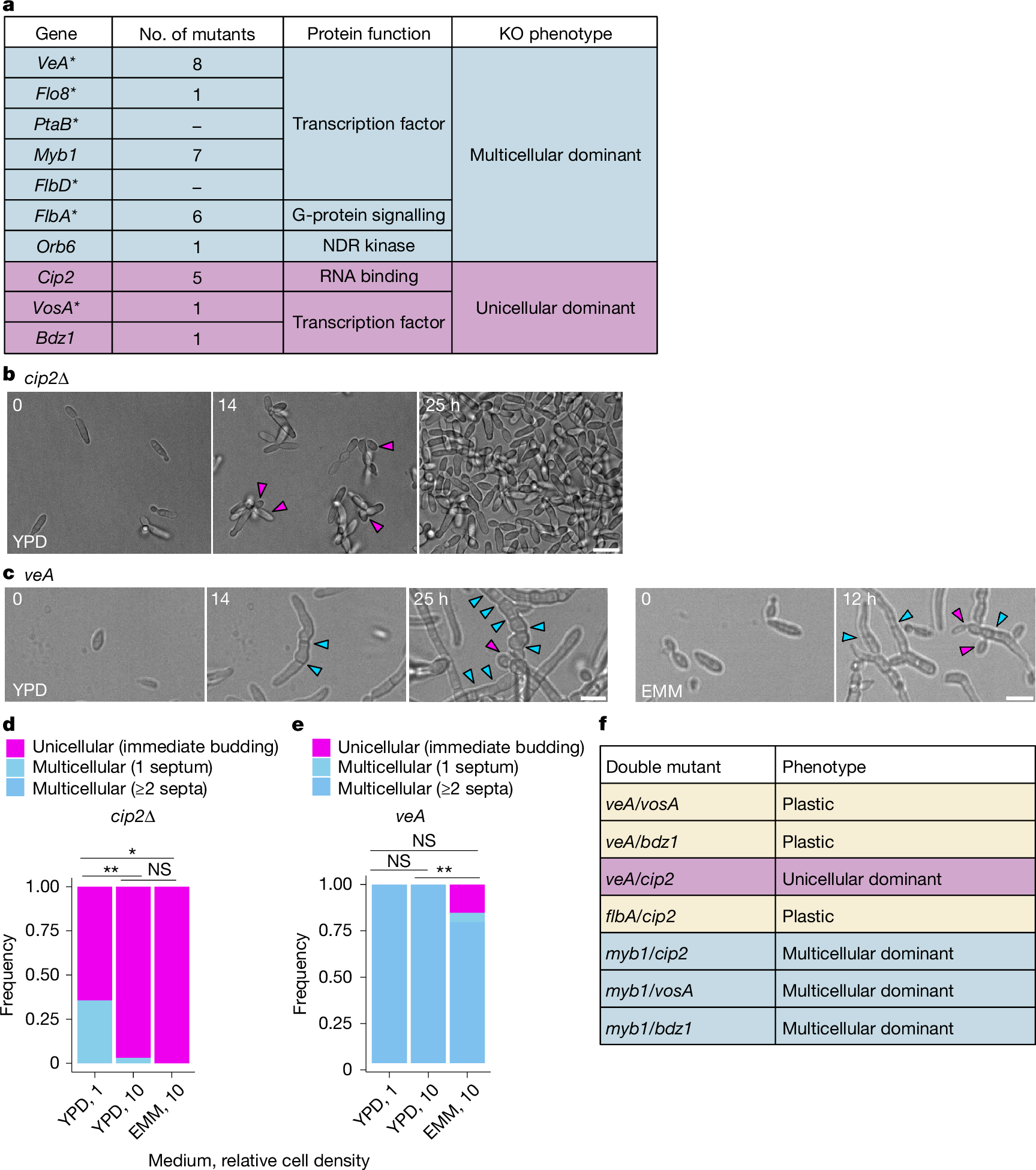

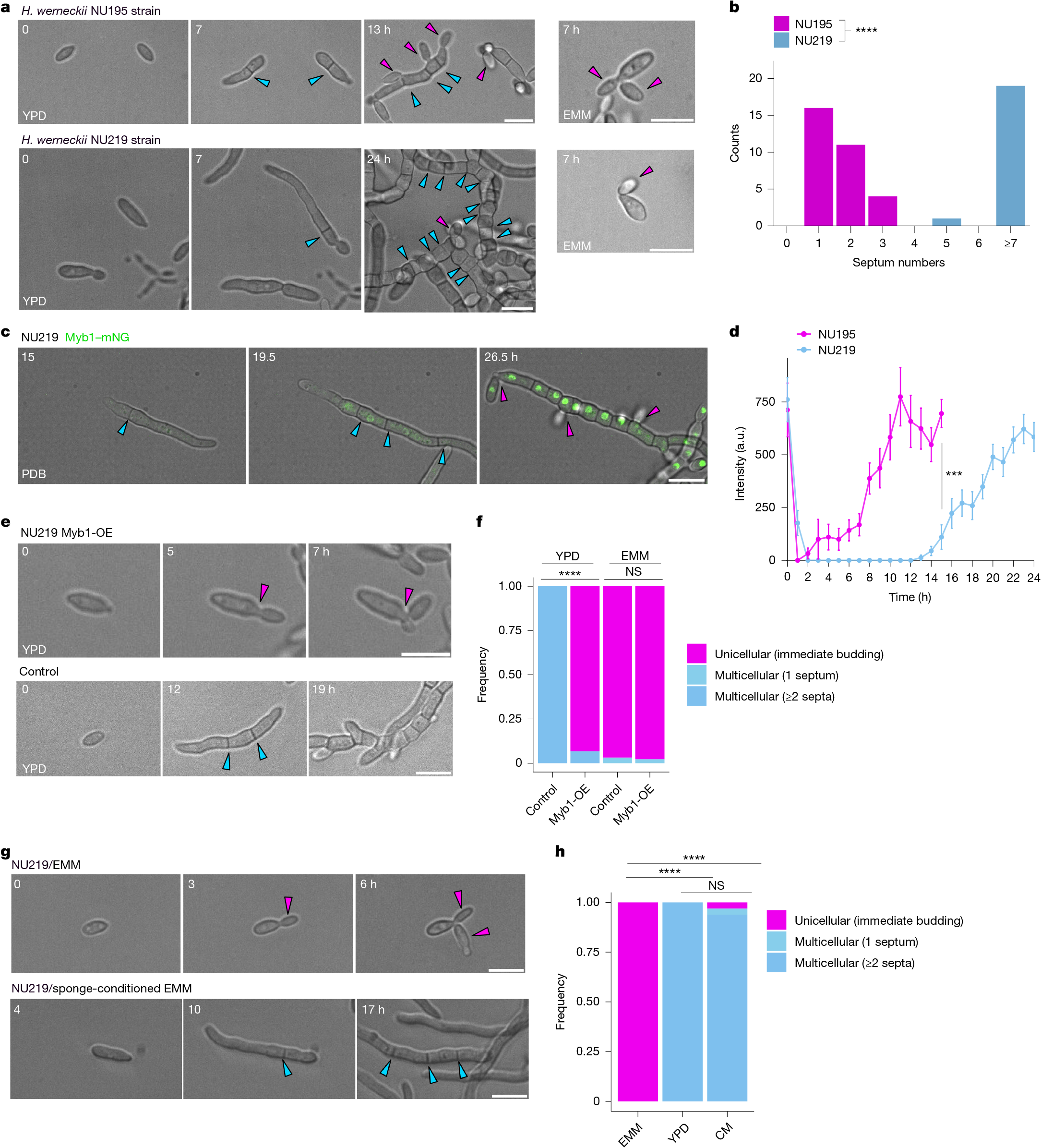

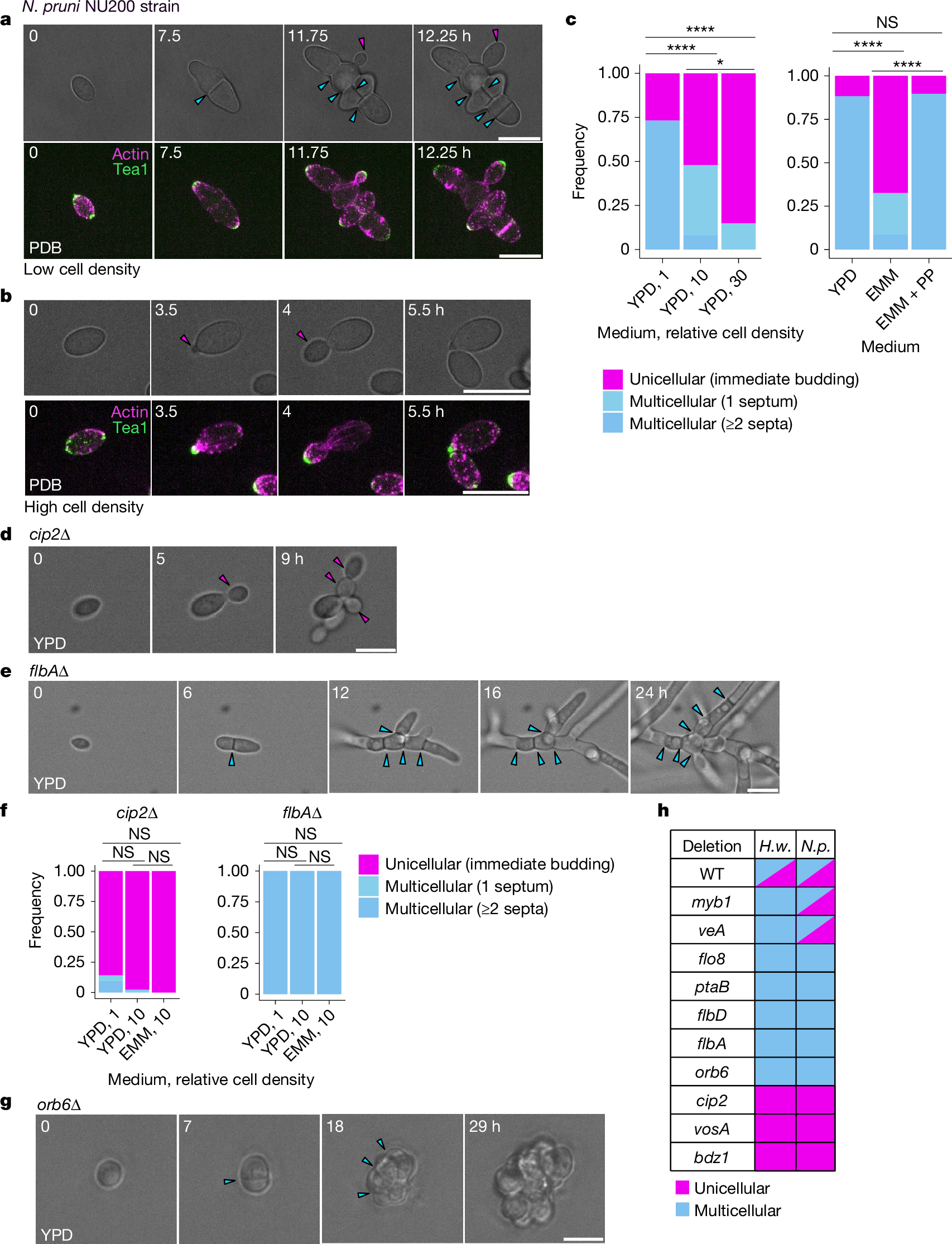

- •Ten genes in Hortaea werneckii regulate facultative multicellularity, with deletions leading to near-obligate unicellularity or multicellularity.

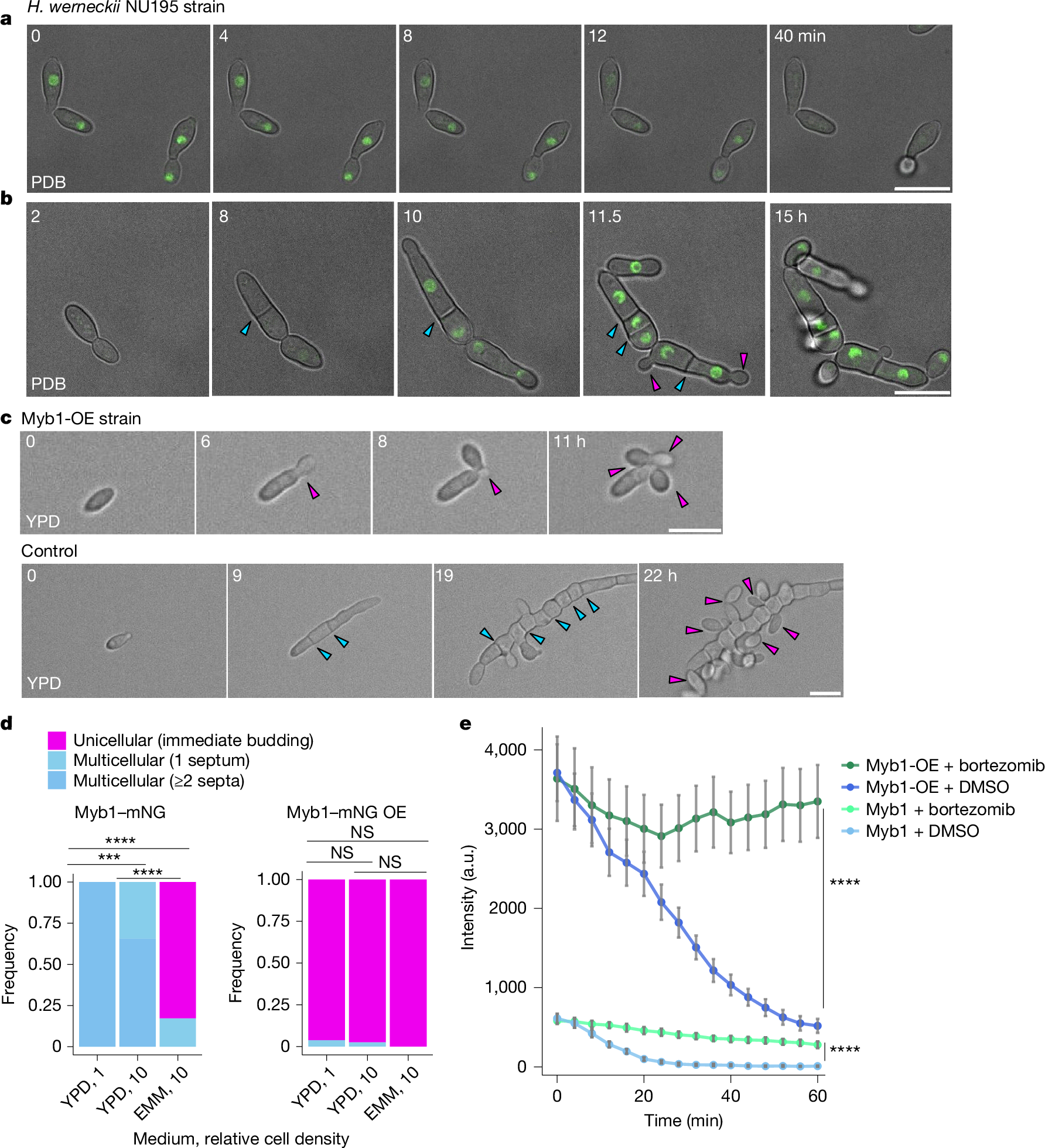

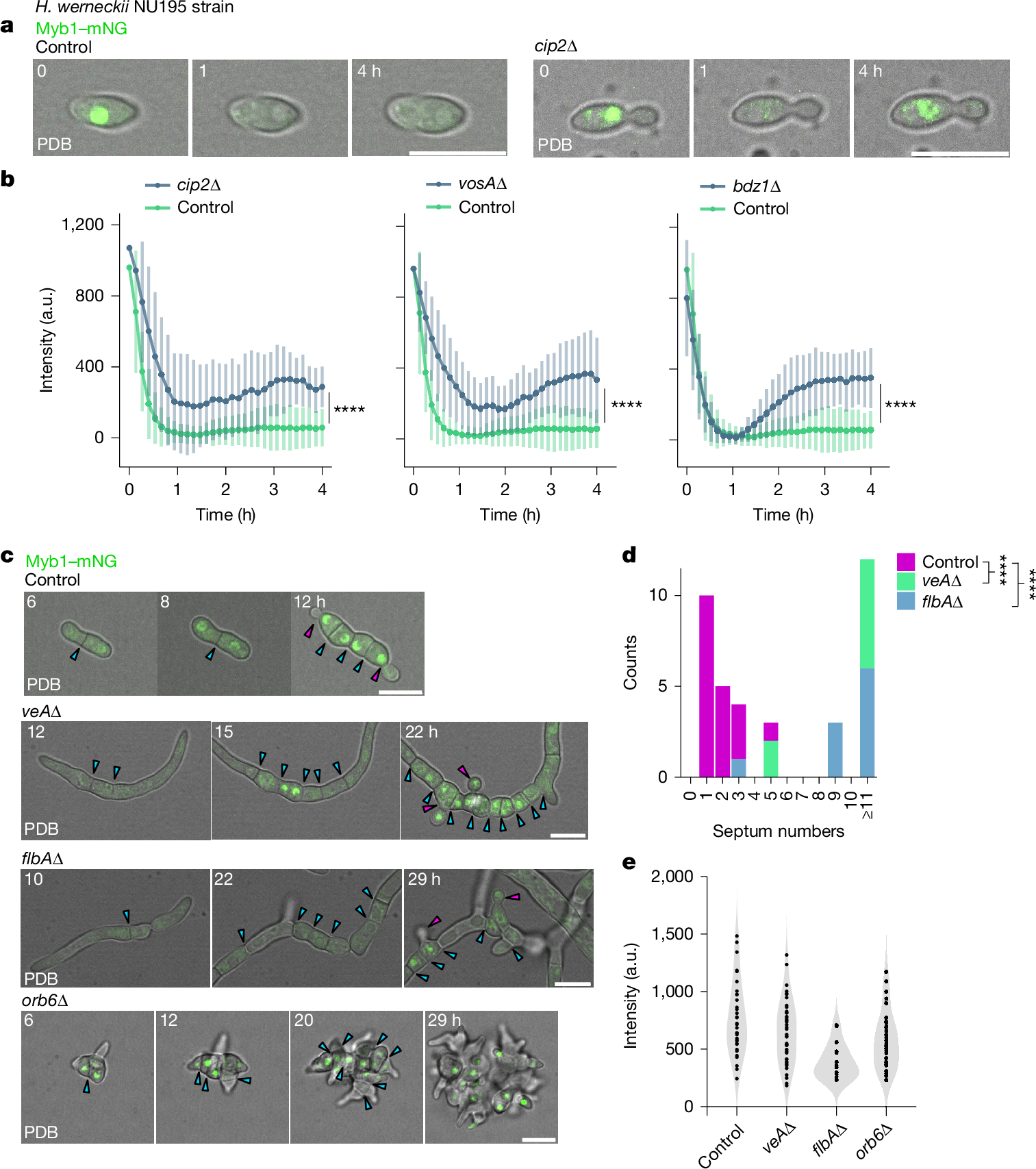

- •A Myb protein acts as a switch-like regulator, with expression and degradation linked to nutrient conditions to stabilize growth states.

- •Genetic flexibility is evident through second-site mutations that can restore or reverse multicellular phenotypes.

- •Ecological factors, such as sponge-conditioned medium, induce multicellularity in H. werneckii, highlighting environmental influences.

- •The study establishes a model system for dissecting multicellularity across genetic, cellular, and ecological scales.

Tags

Abstract

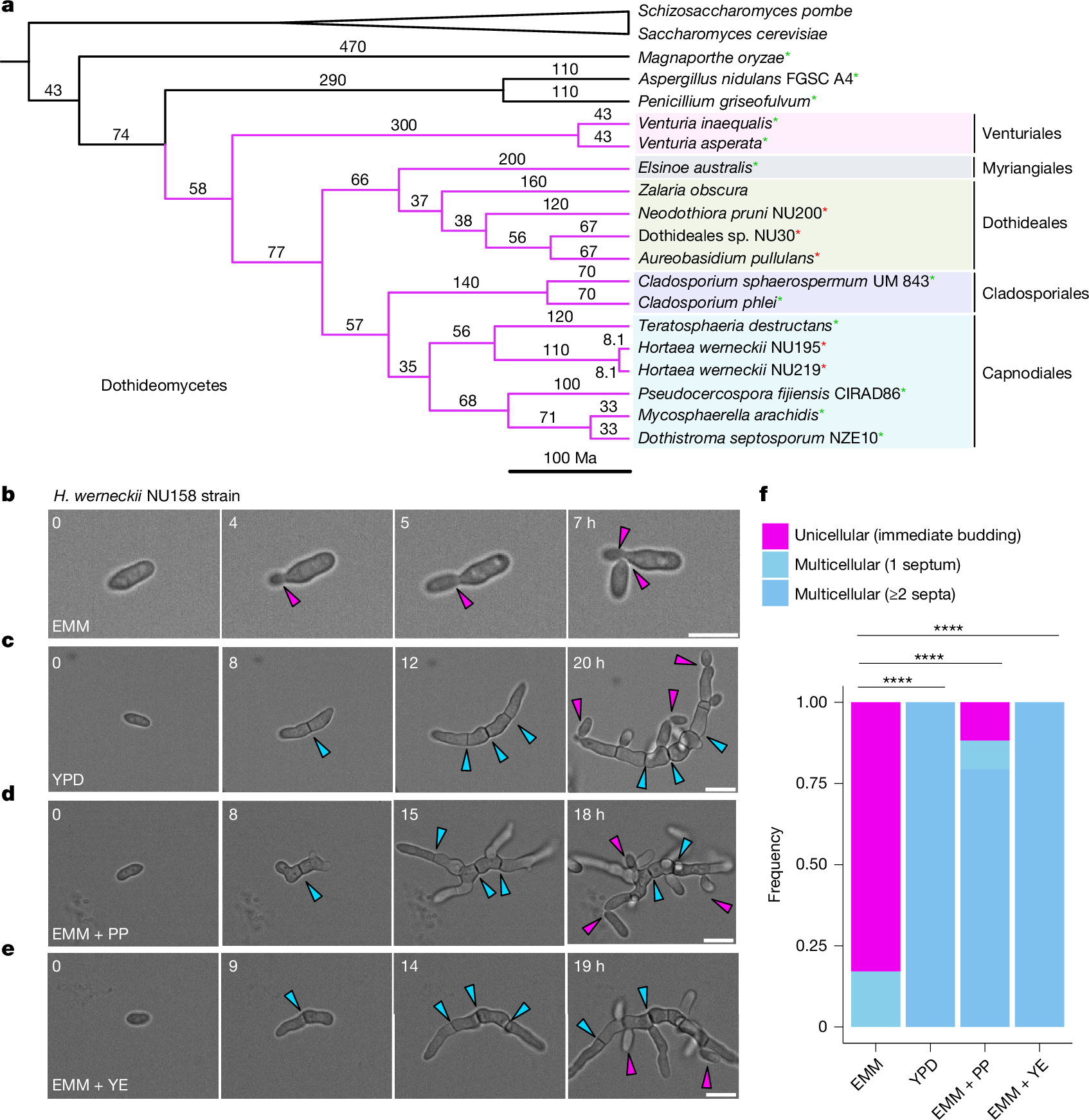

The evolution of multicellularity is considered to be a major transition in the history of life on Earth1. In the evolution from unicellularity to obligate multicellularity, facultative clonal multicellularity may constitute an intermediate state, in which unicellular proliferation and clonal multicellular growth are switchable2,3,4. However, little is known about the mechanisms of switching. Here we identify the genetic and cellular basis of nutrition-responsive facultative clonal multicellularity in two black-yeast species of Dothideomycetes. Deletion of any one of ten genes in Hortaea werneckii5,6 results in near-obligate unicellularity or multicellularity. Six of these genes encode regulators of conidiation (asexual sporulation) in filamentous fungi7, despite conidiation not being observed in H. werneckii. Second-site mutations often restore or reverse the phenotype, revealing genetic flexibility underlying facultative multicellularity. A Myb protein functions as a switch-like regulator of state transitions in H. werneckii; its expression and degradation are coupled to nutrient conditions, stabilizing unicellular or multicellular growth. However, while conidiation regulators are similarly co-opted to enable facultative multicellularity, the Myb gene is dispensable in the related species Neodothiora pruni8, further highlighting molecular diversity in plasticity regulation. Ecologically, multicellular-prone H. werneckii ecotypes are isolated from sponges, and sponge-conditioned medium induces multicellularity. This study establishes a tractable model system for dissecting facultative clonal multicellularity across genetic, cellular and ecological scales, and outlines genetic and cellular strategies to gain, lose and regain multicellularity and, more broadly, phenotypic plasticity.

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Genome duplication in a long-term multicellularity evolution experiment

Stochastic phenotypic switching arises in response to directional selection in experimentally evolved multicellular yeast

De novo evolution of macroscopic multicellularity

Data availability

Raw genomic reads, draft genome assemblies and raw RNA-seq data of H. werneckii strains NU195 and NU219, and raw genomic sequences of Cladosporium sp. NU13 strain, have been deposited to the DNA Data Bank of Japan (DDBJ) under the following accession numbers. DRA019484: raw genomic reads of NU195. DRA019485: raw genomic reads of NU219. DRA021993: raw genomic reads of NU13. BAAGBH010000001–BAAGBH010000351: draft genome assembly of NU195. BAAGBI010000001–BAAGBI010000199: draft genome assembly of NU219. DRX603799–DRX603801: RNA-seq data of NU219 (WT, multicellular). DRX603802–DRX603804: RNA-seq data of NU195 (WT, unicellular). DRX603805–DRX603807: RNA-seq data of NU195 (WT, multicellular). DRX603808–DRX603810: RNA-seq data of NU195 (veAΔ). DRX603811–DRX603813: RNA-seq data of NU195 (myb1Δ). DRX603814–DRX603816: RNA-seq data of NU195 (cip2Δ).

References

Szathmáry, E. & Smith, J. M. The major evolutionary transitions. Nature 374, 227–232 (1995).

Brunet, T. & King, N. The origin of animal multicellularity and cell differentiation. Dev. Cell 43, 124–140 (2017).